Architecture at HSMC

The importance of architecture in the development of the St. Mary’s City museum was realized from the beginning. In the early 1970s, the St. Mary’s City Commission began a project in cooperation with the Maryland Historical Trust to record buildings and better understand the evolution of Maryland domestic architecture. Cary Carson was the museum lead on this; he also conducted research about 17th-century architecture in England.

In the 1950s and 1960s, it was commonly thought that there were many 17th-century structures still standing in the state. However, as the architectural project advanced, these dates were called into question. Archaeological discoveries at the St. John’s and Van Sweringen sites raised still more questions about the nature of the early architecture of the colony. In 1980, to acquire reliable dating evidence, HSMC began another partnership with the Maryland Historical Trust and dendrochronologist Herman J. Heikkenen to sample the timbers of select houses in Southern Maryland and elsewhere to determine their dates of construction. The tree-ring results radically changed understanding of the evolution of housing in the colony and showed that nearly every home believed to date to the 17th century was actually of 18th-century construction (for more, see Heikkenen and Edwards’ 1982 article published in the Association of Preservation Technology Bulletin). Only a few structures in the entire state were built pre-1700, with the oldest being the Quaker Third Haven Meeting House in Easton, Maryland (erected in 1684) and Holly Hill Plantation near Annapolis (built in 1698).

Ongoing archaeology also uncovered the remains of previously unsuspected buildings constructed on wooden posts or piers called earthfast architecture. Working with colleagues in Virginia, it was discovered that the average building in the Chesapeake region in the 1600s had been constructed in this way. Synthesized in a very influential 1981 article titled “Impermanent Architecture in the Southern American Colonies” (Carson et al.), this new evidence helped explain why so few 17th-century buildings in the Chesapeake had survived. HSMC also developed new methodologies for excavating these buildings and Garry Stone and Carson applied the newly acquired data directly as experimental archaeology with the reconstruction of 17th-century buildings as part of the Godiah Spray Tobacco Plantation exhibit in 1981–1983. Since then, architectural research by the museum has continued with the excavation, analysis, and reconstruction of buildings such as the Brick Chapel, Smith’s Ordinary, and Cordea’s Hope.

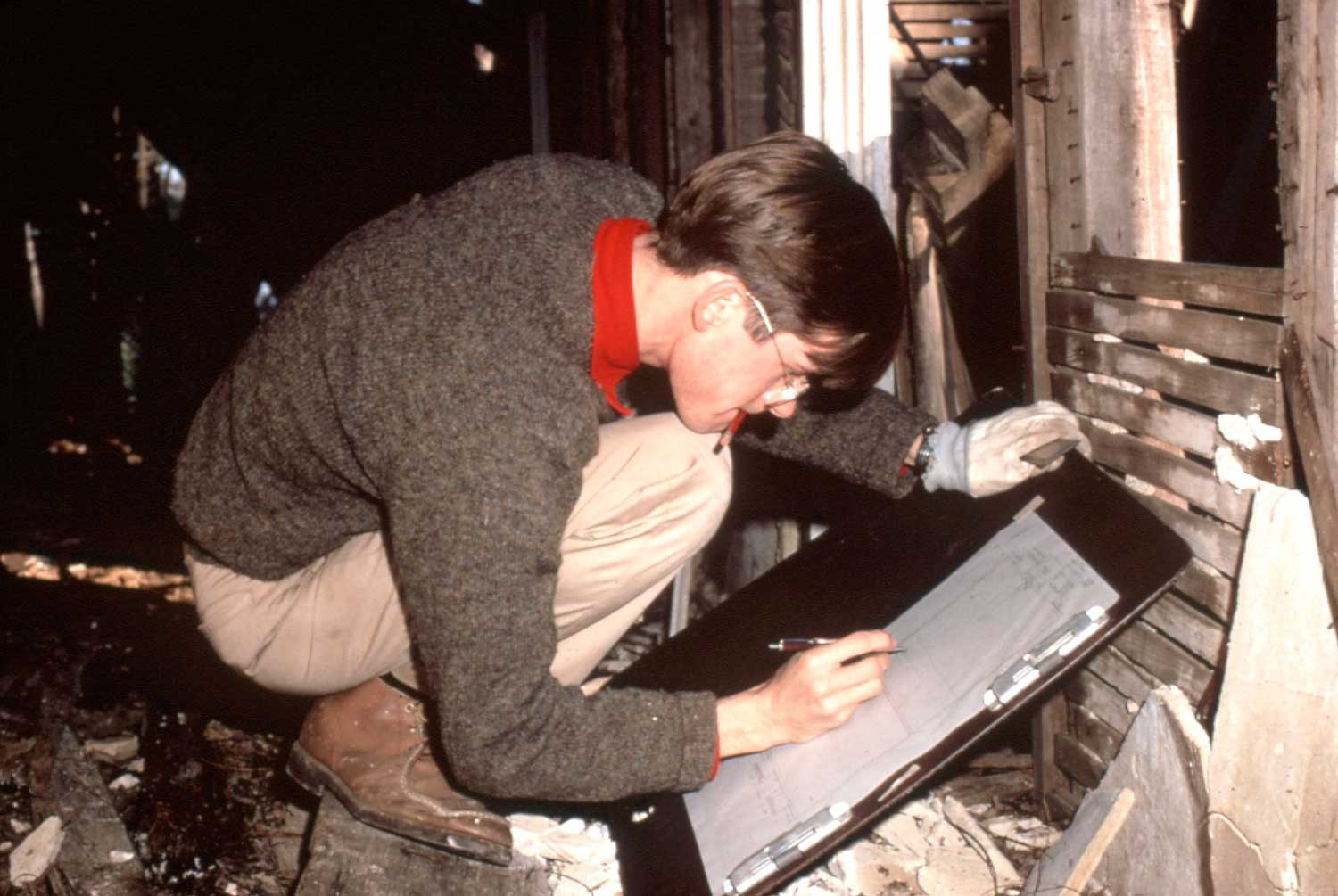

Cary Carson making architectural drawings

Reconstruction of an earthfast building

Reconstruction of an earthfast building