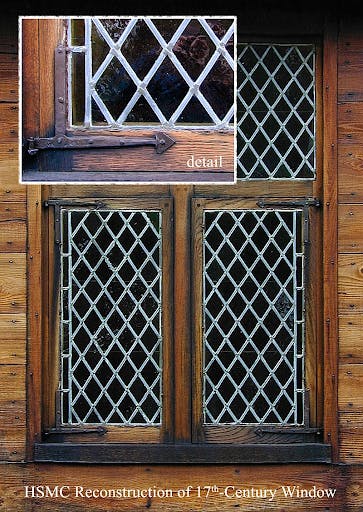

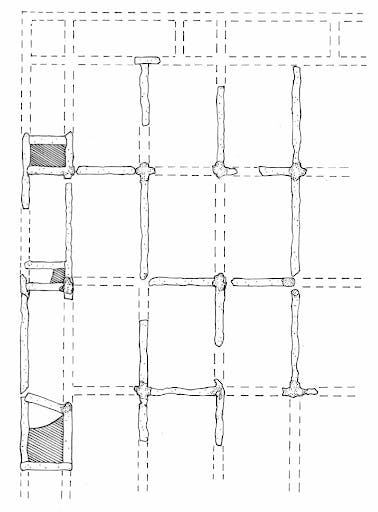

From the first 17th-century investigations at St. Mary’s City, archaeologists began recovering evidence for glass windows. These were expensive items and many immigrants could not afford them. Instead of glass, their window openings were covered with fabric, oiled paper, or perhaps only shutters. No one rich or poor had screens to keep out flies and mosquitoes. But for more wealthy immigrants, glazed windows were commonly used. Seventeenth-century windows were assembled using thin “H” shaped leads. The cut glass panes were set into the open sides of the “H” and the lead pushed tight against them. The lead strips were soldered together as this reconstructed example at Farthing’s Ordinary shows.

Reconstructed Glass Window at St. Mary’s City, showing the soldered turned lead strips holding the glass panes. Photograph by Donald Winter

Reconstructed Glass Window at St. Mary’s City, showing the soldered turned lead strips holding the glass panes. Photograph by Donald Winter

But how do we know what the 17th-century windows in early Maryland looked like? None survive intact from the colony, although there are a few still extant in New England and a number in England. Here is a c. 1675 window in a house I visited in a small village of Chilton Cantelo, Somerset, England.

Original 17th-century window in an English farmhouse known as Higher Farm in the village of Chilton Cantelo, Somerset. Photograph by Henry Miller

Original 17th-century window in an English farmhouse known as Higher Farm in the village of Chilton Cantelo, Somerset. Photograph by Henry Miller

But getting details about the windows in early Maryland houses requires archaeology. This work began with the St. John’s excavations. Four years of excavation yielded about 7500 fragments of glass and window leads. Here are still intact pieces of a window being uncovered at St. John’s in 1973.

Window pieces being uncovered in a large feature in the back yard of St. John’s. The pit was filled around 1690. Photo by Alexander H. Morrison.

Window pieces being uncovered in a large feature in the back yard of St. John’s. The pit was filled around 1690. Photo by Alexander H. Morrison.

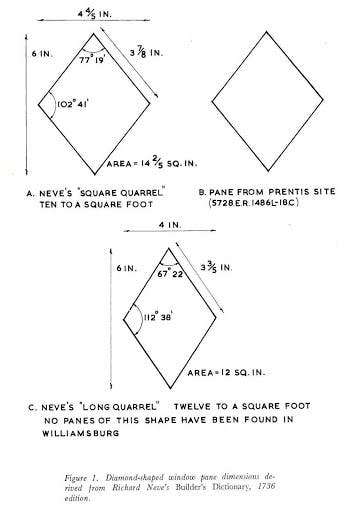

One of the first assignments I was given as the new archaeological curator in 1977 was to analyze the window artifacts. At the time, I was clueless as to how to do it. Fortunately, a few years before, a scholar at Colonial Williamsburg, Isabel Davies, had published a study about windows found at Williamsburg. She emphasized that the angles to which the glass panes had been cut were key to the effort. She included a 1735 print about the two types of diamond shaped glass panes then in common use, as seen below. She uses the more correct period term of quarrel for pane in this. There were two forms and they differed only slightly, with those differences indicated by the angles at which the glass was cut.

Traditional forms of diamond shaped glass panes in 1736. From Davies, Isabel 1973 “Window Glass in Colonial Williamsburg.” Five Artifact Studies. Colonial Williamsburg Occasional Papers in Archaeology, Volume 1. Page 79.

Traditional forms of diamond shaped glass panes in 1736. From Davies, Isabel 1973 “Window Glass in Colonial Williamsburg.” Five Artifact Studies. Colonial Williamsburg Occasional Papers in Archaeology, Volume 1. Page 79.

Following this guide, I began measuring the hundreds of fragments that still had original angles on them. These can be identified by lines along the edges created by it being covered for a time under the lead. This picture shows these lines on several fragments, about one-eight of an inch from the edge. Also notice that the glass is not clear. Seventeenth-century glass was greenish tinted with many irregularities. When long in the ground, soil chemicals work to decay the glass, as these specimens show. This decay process was made painfully obvious to us as I began taking out the window glass fragments from the collection for analysis. Although only excavated five years before, the decay was so advanced on some pieces that these once intact specimens had become small gold-colored fragments and dust at the bottom of the bag. Seventeenth-century glass is not stable and preservation treatment is essential. Therefore, immediately afterward we consulted with conservators at the Smithsonian and began treating all the glass with preservatives; that is now a standard practice for HSMC archaeology.

Close up of some 17th-Century Window glass showing the original edges and the line made by the lead.

Close up of some 17th-Century Window glass showing the original edges and the line made by the lead.

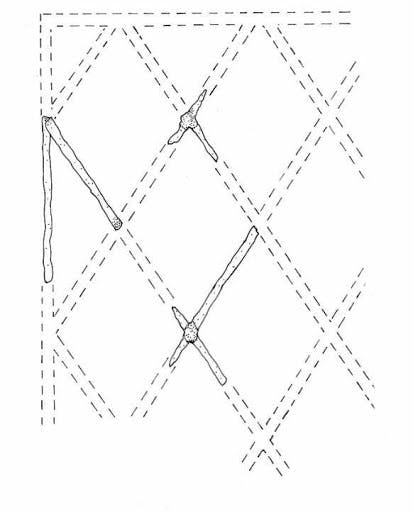

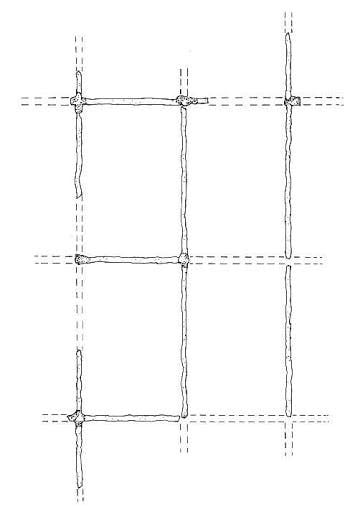

This work revealed that there were two basic window glass shapes used at St. John’s -the common diamond-shaped panes and rectangular panes. One group of window glass from the earliest period were found to be quite different and they are reported in the essay Strange Windows Using both the glass angles and the angles to which the leads were soldered, it was possible to reconstruct the shapes of a number of St. John’s windows. One using the actual artifacts is seen below and drawings of others are also shown.

A Reconstructed St. John’s window using the glass and window leads. Note that on the bottom right is a triangular glass pane still enclosed by the turned leads.

A Reconstructed St. John’s window using the glass and window leads. Note that on the bottom right is a triangular glass pane still enclosed by the turned leads.

Drawings of three other Reconstructed Windows from the St. John’s Site. Second Half of the 17th-century. Drawn by Henry Miller

Drawings of three other Reconstructed Windows from the St. John’s Site. Second Half of the 17th-century. Drawn by Henry Miller

But there was one great secret hidden in these windows about which we were totally unaware. In 1980, an assistant to the great archaeologist Ivor Noel Hume was cleaning artifacts from the very early Martin’s Hundred site in Virginia. Upon scrubbing and partially opening a window lead, they observed these words: “John: Bishop of Exceter Gonner 1625”. The lead contained a name, place and date, and is the oldest dated lead yet known from English America. This was a remarkable discovery and the idea of there being marked window leads excited archaeologists on both sides of the Atlantic. Historic St. Mary’s City conservator Susan D. Hanna began examining St. Mary’s City window leads and soon identified hundreds of marked specimens. She immediately found that conservation was needed on most leads to remove corrosion and allow the letters and numbers to be fully visible. One of the first revealed was made by London glazier Francis Good. Here is one of his marks showing part of his name and the date 1673. The full name had to be reconstructed from different leads.

Lead made by Francis Good of London and dated 1673. There are also Good leads dated 1678.

Lead made by Francis Good of London and dated 1673. There are also Good leads dated 1678.

Another is a William Puryovr, also of London and dated 1678. The vertical bars seen on it are the teeth of the gear wheel of the vice through which the lead strip was run to create the “H” shape. The name and date were engraved on that wheel. Below is another mark dated 1677 with an “EW” but the maker has not been identified.

A William Puryovr turned lead dated 1678 from St. John’s.

A William Puryovr turned lead dated 1678 from St. John’s.

A lead marked “EW 1677”. The EW has not been identified but similar leads have been found in London.

A lead marked “EW 1677”. The EW has not been identified but similar leads have been found in London.

The earliest lead Hanna identified at St. John’s bears this mark “*Abraham *Mountfort*Vicemaker * Taunton*1661”. Taunton is a village in the county of Somerset, England. Other leads date to varied times in the 1660s, 1670s, and early 1680s. The latest marked lead at St. John’s is 1685. Turned leads from other sites were next examined and found to also bear numerous names and dates. The latest lead yet found in St. Mary’s City is dated 1699 and came from the Van Sweringen site.

British scholars believe that these names and dates represent the efforts of the Glazier Guild. Following medieval practices, the Guild sought to ensure quality control by having members mark their products. Shoddy work could range from poor soldering and employing flawed turned leads, to casting with impure lead or skimping on the amount of lead used in casting to below that needed to make strong windows.

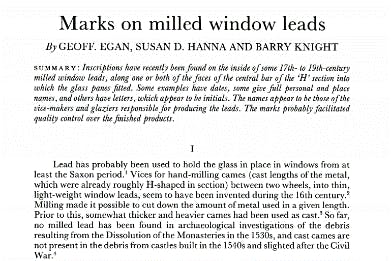

This was a totally new dating tool for historical archaeologists. Hanna took the lead on this research in the United States, and in collaboration with two prominent English archaeologists, Geoff Egan of the Museum of London and Barry Knight of English Heritage, they assembled a database and published the pivotal article about the leads and their value as a dating tool in the international journal Post-Medieval Archaeology in 1986, as seen below.

Analysis of the evidence for window dates on sites shows the significance of this new tool. The dates tend to correspond closely to known construction or renovation times. There is sometimes a lag of a few years between the lead dates and known architecture events, perhaps due to using leads already in stock, delays in shipping, or maybe that glaziers did not alter the vice wheel on an annual basis. In other cases, the lead dates and time of construction correspond precisely. These dates on the leads represent what archaeologists call a “terminus post quem” (TPQ), Latin for the date after which something happened. Work on this material continues. HSMC conservators recently completed the cleaning and preservation of hundreds of window leads from the Anne Arundel site located where the new archaeological lab now stands. We thought the site was an ordinary called Providence, and the 1680s dates on those leads match the historical record well. And currently, I am writing a new study about window leads for Post-Medieval Archaeology to continue HSMC’s role in advancing this important analytical method.

Window leads are a valuable resource for historical archaeologists, although totally unknown before the early 1980s. Historic St. Mary’s City played a central role in the development of this significant dating tool. And we can hope that future excavations will find a much earlier dated lead than 1661, perhaps even one from Maryland’s first years in the 1630s.

About the Author

Dr. Miller is a Historical Archaeologist who received a B. A. degree in Anthropology from the University of Arkansas. He subsequently received an M.A. and Ph.D. in Anthropology from Michigan State University with a specialization in historic sites archaeology. Dr. Miller began his time with HSMC in 1972 when he was hired as an archaeological excavator. Miller has spent much of his career exploring 17th-century sites and the conversion of those into public exhibits, both in galleries and as full reconstructions. In January 2020, Dr. Miller was awarded the J.C. Harrington Medal in Historical Archaeology in recognition of a lifetime of contributions to the field.