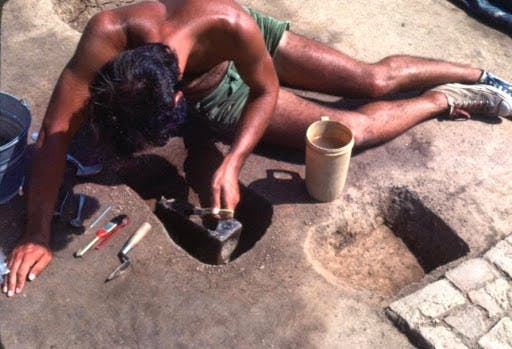

Over the many years archaeologists have explored St. Mary’s City, thousands of intrusions into the ground have been revealed. We call them features and with “dirt reading” experience, most can be identified as post holes, fence ditches, tree roots or trash filled pits. But why some were ever created remains unexplained. One especially perplexing case was found at the Van Sweringen site in 1978. Under the plowed soil, excavators defined a semi-rectangular feature about three feet long and displaying a general shape we thought looked like a giant’s footprint. Archaeologist Gordon Fine was assigned the task of excavating this feature. Placing a string line at the middle of the feature’s length, he began excavating one half. Digging up to the string line would give us a cross-section view of the intrusion that is an important piece of archaeological evidence. About two inches down, his trowel encountered a hard object. Careful excavation around it revealed that the object was actually a buried bottle. This picture shows Fine uncovering it.

Next you can see the glass bottle fully uncovered. It was a square sided type we call a Case Bottle. These are given that name because their shape allowed them to be placed in a wooden case for storage and shipping. An added advantage is that the case could be locked to keep people for sampling or stealing the contents. This bottle had been placed on its side at the bottom of the shallow pit and downward pressure, probably from a tractor, had caused the top side to be broken.

The First Case Botte Uncovered

The First Case Botte Uncovered

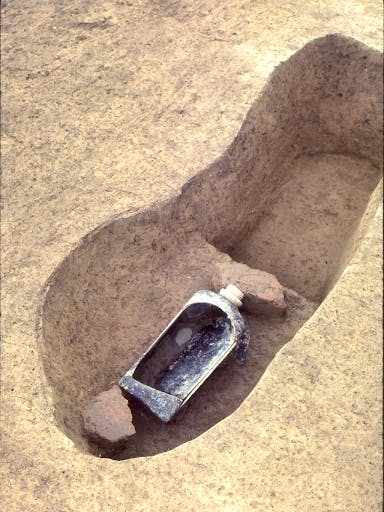

After drawing the cross-section, excavation continued on the second half of the feature. To our total surprise, this revealed another complete case bottle in that half. This one was laying between two half bricks and once had a pewter cap that allowed it to be screwed shut. Unfortunatly, the cap was missing. Based on the evidence, these bottles probably date to the last quarter of the seventeenth century.

The Second Case Bottle in the Small Pit. You can see here why we described the feature’s shape as like a giant footprint

The Second Case Bottle in the Small Pit. You can see here why we described the feature’s shape as like a giant footprint

The two bottles were brought into the lab, where they needed to be washed, conserved and reassembled. But further inspection and additional excavation were first needed. As Laboratory Curator at the time, I knew that in the seventeenth century, bottles were sometime buried as part of a magical practice. Called Witch Bottles, these were inentionally placed near hearths or doors to protect the house and ward off evil. Intact witch bottles found in England contain bent nails or pins, hair and fingernail trimmings, and usually have a piece of cloth cut into a heart shape with pins inserted into it. The final ingrediient was sometimes urine. The ideas behind this combination of substances are not clear. Here is a picture of one intact Witch Bottle found in England. Its cork was still good and all the contents were well preserved. It seemed reasonable to think that some early Maryland settlers might carry this aspect of folk belief with them to America.

Rhenish Brown Stoneware “Bellarmine” bottle used as a Witch Bottle with its contents still preserved

Rhenish Brown Stoneware “Bellarmine” bottle used as a Witch Bottle with its contents still preserved

The two Van Sweringen bottles after reconstruction are seen below. Could they have been Witch Bottles? We decised to remove them from the burial site and take them to the lab without disturbing the soil within them. I knew that the interiors had to be carefully excavated to see if they contained anything. While the cloth and other organic inclusions would have decayed, the metal would still be there.

The only other known instance of buried bottles in the Chesapeake known at that time was at Colonial Williamsburg where the great archaeologist Ivor Noel Hume in the 1960s found a group of round wine bottles buried at Wetherburn’s Tavern. Dating from the 1750s, some of them were remarkably still sealed. Upon opening them in the lab, it was found that they contained cherries with the pits still perfectly preserved; Noel Hume speculated that they were perhaps being soaked in brandy. If ours were not witch bottles, maybe they had been buried for the same reason as those at Williamsburg.

The two Van Sweringen bottles afterconservation and restoration

The two Van Sweringen bottles afterconservation and restoration

With these two possibilities in mind, I began gently removing the interior contents with great anticipation. The first one we had discovered held only soil. But the other was more intact and seemed more promising. Slowly, its contents were removed using a dental pick and spoon. And at the bottom – Nothing! There was no evidence that we had found the first Witch Bottles in Maryland, or 17th-century brandied fruit.

This probably should not have been a surprise as they were not buried near a hearth or door but were outside in the yard. But both had clearly been intact, still usable bottle when buried. Although the pewter cap was missing, they could have been placed in the pit with corks sealing them. If so, we would have expected the colonist to have used wire to better secure the corks in place during the time they were buried. Despite very close examination, no traces of corks or wire were present.

So why were these two still good bottles buried? Perhaps they were temporarily interred to allow fermenting or the infusion of alcohal into some substance and forgotten about. Or did they contain something that went bad and could not be cleaned out, or was so fouled that burial was necessary? But if so, why not just throw them on to a midden with the rest of the 17th-century trash? We dug middens at the site that contain the fragments of many other wine bottles along with bones and other waste. We cannot explain this nearly 350 year old act. Can you suggest a reason for their interment? For the HSMC archaeologists, despite years of pondering this discovery, the reason for their burial is as much of a mystery today as it was in 1978. But such is often the way of archaeology, raising new questions even as we find the answers to others.

About the Author

Dr. Miller is a Historical Archaeologist who received a B. A. degree in Anthropology from the University of Arkansas. He subsequently received an M.A. and Ph.D. in Anthropology from Michigan State University with a specialization in historic sites archaeology. Dr. Miller began his time with HSMC in 1972 when he was hired as an archaeological excavator. Miller has spent much of his career exploring 17th-century sites and the conversion of those into public exhibits, both in galleries and as full reconstructions. In January 2020, Dr. Miller was awarded the J.C. Harrington Medal in Historical Archaeology in recognition of a lifetime of contributions to the field.