The most impressive funerary monument of the Calvert family is that of Anne Mynne Calvert. She was George Calvert’s first wife and the mother all but one of his children. Anne married George Calvert in 1604 and became the mother of 11 children, including Cecil and Leonard. Her sudden death on 8 August 1622 devastated her husband and family. Anne was initially buried at their family parish of St. Martin’s in the Field in London. However, she was later moved to her home parish church of St. Mary’s in the village she grew up in, Hertingfordbury in the county of Hertfordshire, just northeast of London. This is the church today, which was built in the 1200s. Anne was the daughter of George and Elizabeth Mynne, substantial land owners in the area, and their home stood where the White Horse Hotel now operates in the center of the village. Both her parents were buried in St. Mary’s Church.

St. Mary’s Church, Hertingfordbury, England. All Photographs by Henry Miller.

St. Mary’s Church, Hertingfordbury, England. All Photographs by Henry Miller.

There an elegant chest tomb was installed in the chancel or altar area of the church along its north wall. Also known as the Gospel side, this was a most prestigious location. While we cannot prove it at this time with the available information, it is likely that Anne had been buried in a lead coffin at St. Martin’s. Her tomb is described as still being on the north side of the chancel in an 1881 publication, but during renovations of the church in 1888-89, her monument was move to the less prestigious location in the bell tower, where it remains today as seen here.

Lady Anne Mynne Calvert’s Tomb, c. 1623

Lady Anne Mynne Calvert’s Tomb, c. 1623

The monument is a chest tomb (also called an altar tomb), with a backplate rising to an entablature with a crest surrounded by clusters of fruit. Anne’s remains are in the chest, which is capped with a slab of black limestone upon which rests an alabaster sculpture of her. Identification of the stone was made by chemical tests in 2013 with the assistance of geologist James Walker. She is lying on her back, her head supported upon an elegantly embroidered pillow with tassels painted gold, and her hands resting gently at her sides. Anne wears a richly embroidered gown with lace, full sleeves with cuffs, and a ruff about her neck. Anne’s head is covered with a folded kerchief that mostly hides her hair. And her body is wrapped in a cloak displaying more embroidery on the edge (although somewhat damaged), with the cloak covering her from the waist down. If the carving is accurate, Anne was about 5 feet 2 inches tall.

The Carved Figure of Anne Mynne Calvert, St. Mary’s Church, Hertingfordbury, England.

The Carved Figure of Anne Mynne Calvert, St. Mary’s Church, Hertingfordbury, England.

The delicacy of the stone carving and effort at naturalism is well displayed by the representation of her right hand and forearm as seen here. Although her little finger is damaged, the carving was precise and included well-defined fingernails.

Detail of the sleeve and right hand of Anne Mynne Calvert

Detail of the sleeve and right hand of Anne Mynne Calvert

Anne’s face is also carefully defined but her nose and lip were damaged according to legend by Cromwellian soldiers during the English Civil War. This is the only known image of her. I suggest that her face was carved using a miniature painting or perhaps from a death mask. A miniature of George Calvert has survived and it is feasible that one was also painted of his wife as well. Unfortunately, no such miniature of Anne is known, although if it does survive, it would be one of the many that are unattributed or misidentified. Other tomb sculptures of this era made a serious attempt to accurately portray the individual, a trend toward greater realism that was becoming popular. According to one scholar, realistic portraiture of the deceased became fashionable in the second decade of the seventeenth century in England. The body was typically depicted laying recumbent and appearing asleep in death. This is in strong contrast to the more rigid funerary sculpture of the late Medieval era and through the sixteenth century.

The face of Anne Mynne Calvert.

The face of Anne Mynne Calvert.

As noted above, she is wearing an elegant dress with what appears to be embroidered decoration as seen below. A piece of jewelry, perhaps a diamond and precious stone brooch, is centered on her chest at the top edge of the dress.

Detail of the Dress and Ruff Anne is shown as wearing.

Detail of the Dress and Ruff Anne is shown as wearing.

This form of wardrobe was popular in the first quarter of the seventeenth century, and a similar costume can be seen on some paintings. Below are two examples, one a young woman and the other Elizabeth, the Queen of Bohemia. She was the eldest daughter of King James I and Anne of Denmark. As an aside, we know that George Calvert was sent on a mission to meet with the Bohemian Queen.

Women wearing dresses and a ruff similar to that of Anne Calvert. Left is A Girl of the Morgan Family, aged 17, 1620 found at http://www.nationaltrustcollections.org.uk/object/1553684 . Right is Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Bohemia, daughter of James I, c. 1625 or later. After Michiel Jansz Miereveldt, at http://www.nationaltrustcollections.org.uk/object/1151366

Women wearing dresses and a ruff similar to that of Anne Calvert. Left is A Girl of the Morgan Family, aged 17, 1620 found at http://www.nationaltrustcollections.org.uk/object/1553684 . Right is Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Bohemia, daughter of James I, c. 1625 or later. After Michiel Jansz Miereveldt, at http://www.nationaltrustcollections.org.uk/object/1151366

Anne was born on 21 October 1579. Some have suggested that she served as a Lady-In-Waiting to Queen Elizabeth 1, although I cannot confirm this. But it is probable that she met George in London. He was an assistant to the powerful Robert Cecil, and as such was somewhat involved in courtly activities there. While the circumstances of their meeting and courtship will never be known, it is certain that they were married on 22 November 1604 at the Church of St. Peter’s Cornhill in London. Anne and George had a total of eleven children. She must have been most proud when George was knighted by King James I in 1617, making him Sir George and her Lady Anne Calvert. But five years later in early August of 1622, Anne was pregnant and suddenly experienced some type of illness. A few days later, she died while giving birth to a son they named John who also died. George and the family were stricken with grief and George wrote that he faced “many images of sorrow” and that he had lost the one person “who was the dear companion and only comfort of my life”. The diary of William Camden’s records that in August of 1622 “The wife of Secretary Calvert, a most modest woman, is dead”.

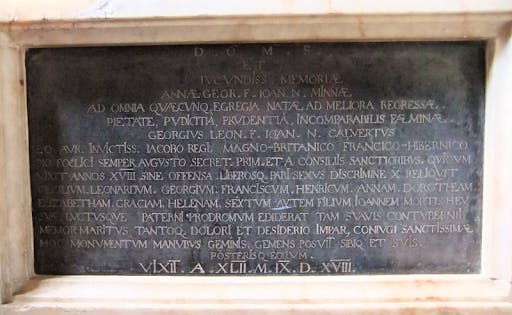

The depth of George’s grief and his way of honoring her is indicated by a plaque that he had mounted on her tomb, as seen here. It was written by George in Latin and there have been several attempts at translation. The following is a synthesis of these I have made in consultation with Latin scholars.

The Plaque on Anne Mynne Calvert’s tomb and a translation of the words below.

The Plaque on Anne Mynne Calvert’s tomb and a translation of the words below.

Sacred to Almighty God and to the most pleasant memory of Anne Mynne, daughter of George and granddaughter of John Mynne, a woman born for all outstanding things, and returned to better things, incomparable in piety, modesty, prudence. George Calvert, son of Leonard and grandson of John, Knight, Chief Secretary and Privy Councillor to the invincible James, King of Great Britain,, France and Ireland, Pious, Fortunate, and always August, with whom she lived 18 years, without offense, and left ten children equal in the distinction of sex: Cecil, Leonard, George, Francis, Henry, Anne, Dorothy, Elizabeth, Grace, Helen, and moreover a sixth son, John, joined alas in her death, went as a forerunner to his fathers mourning. Her husband mindful of so sweet a wedded life, overcome by so great a pain and grief and longing, has placed with his hands this monument to his wife for himself, his children, and their posterity. She lived 42 years, 9 months and 18 days.

George Calvert also included heraldry on the monument. Use of heraldry remained important on funerary memorials, often depicted in oval cartouches with classically influenced surrounds. On the monument are two coats of arms below the entablature on the backplate. The left one is the familiar Calvert black and gold coat while that on the right is the Mynne family coat. These are combined in a symbolically significant larger coat of arms centered above the entablature, supported by beautifully carved clusters of fruit. As a side note, Calvert descendant Barry McGowen pointed out to me that the painter made a mistake in the heraldry. For the Calvert Coat of arms, the far left stripe should be gold, but it is painted in black here.

The entablature, cartouches and fruit decoration above Anne’s figure.

The entablature, cartouches and fruit decoration above Anne’s figure.

What is intriguing is that the Mynne arms are red and white in color and include Cross Botany symbols. These are especially prominent on the tombstone of Anne’s brother George, found elsewhere in the church as seen here. Most of his stone is covered by pews but it appears the two of the crosses were intentionally defaced, perhaps by the Puritan troops in the 1640s.

Tombstone of George Mynne in St. Mary’s Church. Died 1656.

Tombstone of George Mynne in St. Mary’s Church. Died 1656.

The Calvert-Mynne Coats and Lord Baltimore’s Coat of Arms.

The Calvert-Mynne Coats and Lord Baltimore’s Coat of Arms.

This is the first place where the Calvert Coat appears in combined with Cross Botanies and red and white colors. As former State Archivist Edward Papenfuse has argued, the coat of arms for Maryland may be a combination of the Calvert and Crossland and Mynne family arms. It became the hereditary coat of arms for Lord Baltimore and placed on the Great Seal of Maryland. George Calvert clearly had a role in its design soon after he became Lord Baltimore. In creating it, was George not only honoring his mother but also his recently deceased wife? We cannot prove it one way or the other, but the similarity is striking when you first see this tomb. The cartouche on it carries such a resemble to what would later become the coat of arms of Lord Baltimore and subsequently of Maryland.

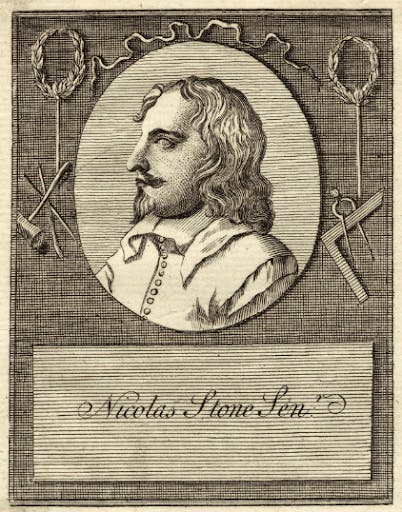

A final question is who made this magnificent monument? After researching the possibilities as to sculptors active at the time while in England and visiting a number of tombs, the artisan who seems to have produced monuments most comparable to Anne Calvert’s tomb was the Master Mason to King James I – Nicholas Stone. Trained in the Netherlands, Stone was a close friend of Inigo Jones and helped him build the first fully classically inspired building in England, The Banqueting House in London. Stone took on many assignments including the controversial porch of the University Church of St. Mary’s in Oxford. He also produced numerous funerary monuments and kept an account book and wrote some remembrances. Unfortunately, there is no complete listing of all his works, and the Calvert tomb is not mentioned in the account book; there are a number of other known omissions as well.

Stone used a naturalistic style of the human form on funerary monuments, and in the 1618-1625 period, employed fruit clusters, created cartouches with the same surrounds as seen on the Calvert monument, and used spiral elements for decoration. A very similar treatment is seen on the 1623 tomb of Lord Kennett that Stone is known to have produced. The overall form of her chest tomb and the decorative devices makes Stone a good candidate as the artisan.

Other evidence is also relevant here. The Calverts and Stones worshiped together St. Martin’s in the Fields church and Stone’s workshop was at the end of Long Acre, where it intersected St. Martin’s Lane, the street on which the Calvert’s home stood. And as a Principal Secretary of State for England, Calvert would have undoubtedly had access to the services of the Royal Master Mason. I suggest that this and other data points to Nicholas Stone as the artist.

Nicholas Stone, Sr., Master Mason to Kings James I and Charles I. From https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/person/mp55167/nicholas-stone-sr.

Nicholas Stone, Sr., Master Mason to Kings James I and Charles I. From https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/person/mp55167/nicholas-stone-sr.

We can gain some sense of the cost for Anne’s tomb from Stone’s account book. For a monument of the size and type as hers, the cost would have probably been in the 80£ to 100£ sterling range, a very substantial sum. Given time for production, the work could have been finished late in 1622 but more likely was completed and installed in 1623. Anne Mynne Calvert’s tomb was made in a fashionable up to date style by the leading sculptor in England at the time. It was eloquent without being ostentatious. Indeed, the backplate could have been much larger and far more impressive. However, for a woman described as Pious and Chaste and Modest, an overly fancy tomb perhaps would have been inappropriate.

What is remarkable is that this monument has survived with so little damage for almost 400 years. Quite a few of Stone’s other funerary works have been destroyed. When it was installed, a religious service almost certainly was held for Anne in St. Mary’s Church in her hometown. At that service, the Calvert children would have read or had translated for them the Latin inscription their father wrote. It concludes with the statement “

“her husband, in memory of so sweet a wedded life, overcome by so great pain and grief, sorrowing, has placed with his hands this monument to his sainted wife, for himself, his [children], and their posterity.”

Today, this superb monument continues to be a memorial to Anne Mynne Calvert and her posterity, who make up the many descendants of the Calvert Family, and in another sense as the mother of the founding family, the citizens of Maryland.

About the Author

Dr. Miller is a Historical Archaeologist who received a B. A. degree in Anthropology from the University of Arkansas. He subsequently received an M.A. and Ph.D. in Anthropology from Michigan State University with a specialization in historic sites archaeology. Dr. Miller began his time with HSMC in 1972 when he was hired as an archaeological excavator. Miller has spent much of his career exploring 17th-century sites and the conversion of those into public exhibits, both in galleries and as full reconstructions. In January 2020, Dr. Miller was awarded the J.C. Harrington Medal in Historical Archaeology in recognition of a lifetime of contributions to the field.