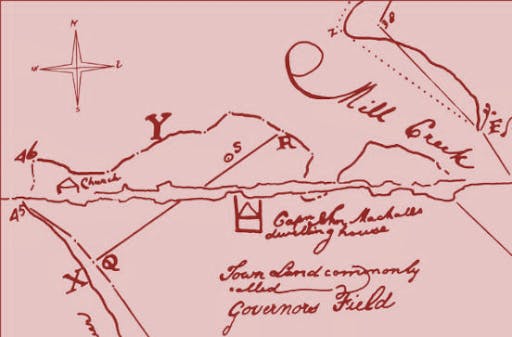

One of the few brick buildings known to have stood in Maryland’s first capital was a jail or prison for the colony built between 1674 and 1676. The only evidence about its location comes from the oldest surviving map of St. Mary’s City, prepared in 1787 by surveyor Jesse Locke. While crude, it shows Trinity Church (which was the 1676 Statehouse at that time), Captain John Mackall’s “dwelling house”, described as “old and crazy” in a later document, and Mill Creek. Just above the house is a circle with the letter “S”. This is identified on the map legend as “Designates the place a old Prison House stood.” The ruins of the jail must have still been very prominent in 1787.

Jesse Locke Map of St. Mary’s City in 1787, showing key landmarks of that time.

Jesse Locke Map of St. Mary’s City in 1787, showing key landmarks of that time.

Unfortunately, the map does not scale precisely with modern topographic maps so the jail’s location can only be roughly placed within several hundred feet. In that area there is a modern road, Trinity Parish Hall and Kent Hall with numerous utility lines. It was feared that all trace of the brick jail was probably destroyed by these many later activities.

This changed on the afternoon of 7 July 1994 when I received a call from the College facilities department. They had decided to make the old tennis court next to Kent Hall into a parking lot and were cutting an entrance from Route 584 (Trinity Church Road). The grader had removed over two feet of fill and then uncovered brick rubble and they stopped the excavation so we could inspect it. Most of the brick was from the 1940s construction of Kent Hall, although some oyster shell and fragments of older brick were also seen. The college agreed to halt further work until we could investigate. With the help of field school students and some volunteers, we returned the next day and found several linear features that might have been colonial fence lines. However, digging them revealed that one was a pre-1940 electrical line and another was a television cable buried in the 1970s. But there was another area with more rubble, some of which appeared to be 17th-century pantile. Our efforts focused upon this area which provided to be the top edge of a deep ravine. Here are field school students digging the first units.

Archaeology Field School Students excavating units in the newly exposed area next to the Tennis Court. The edge of the tennis court is seen at the top left.

Archaeology Field School Students excavating units in the newly exposed area next to the Tennis Court. The edge of the tennis court is seen at the top left.

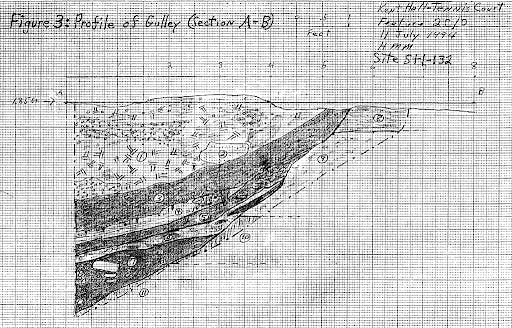

As we got deeper, a layer of dark soil was found with some brick and shell fragments. Below that was a wash layer and then a thick deposit of brick, pantile and a few 17th-century artifacts. A deep ravine had once existed here and it was filled over time. This photo shows you the layers we exposed. The students helped me draw a profile of the layers that is also seen below.

Photograph of the layers as exposed in the filled ravine.

Photograph of the layers as exposed in the filled ravine.

Drawing of the layers as seen in the filled ravine.

Drawing of the layers as seen in the filled ravine.

We had discovered the eastern edge of a deep ravine that once ran down toward the St. Mary’s River. The lowest layer along the edge contained architectural debris and 17th-century artifacts. Above that was a sandy wash layer and some more fill. The dark strata in the middle of the cross-section had root molds extending from the bottom of it, implying that this was an organic layer of topsoil that had developed in the ravine. It was later covered by a thick deposit of mixed topsoil and subsoil that filled the entire old depression. Subsequent excavations under the old Tennis Court revealed that the ravine had been quite large and had begun near the road and the adjacent corner of Kent Hall. It then expanded toward the river where the college boat house now stands. A very large volume of soil was need to fill this large ravine. Where could it have come from? There were only a few oyster shell fragments mixed in it and no really dateable artifacts.

Several years later, while monitoring large scale mechanical excavations under the old tennis court, Ruth Mitchell observed something deep in the fill. Due to the unstable soils, we could not safely go down into the excavation pit to see what it was. The problem was solved when archaeologist Robert Bray volunteered to be lowered in the bucket of the large earthmover. Dangling from it at a depth of about 12 feet, he retrieved a piece of pottery. It was a ceramic called Whiteware and dates after c. 1815, a most important clue. The fill had to date after that but before 1911 when the original tennis court was built there. We turned to the historical record to try and determine where such a massive volume of soil could have come from. The most probable origin was the excavation of the foundations and cellar for Calvert Hall in the 1840s., or perhaps St. Mary’s Hall in 1906. The sheer quantity of soil involved suggests it was more likely from Calvert Hall. Such an excavation would have necessitated the disposal somewhere of the earth . Given the technology of the time, moving a large volume of soil any distance would have been difficult and expensive. The ravine was close by and apparently viewed as a most convenient dump site. This action produced a very significant change in the landscape of St. Mary’s City that was completely unknown previously. That finding would have significance for understanding the layout of the first city.

Much rubble was found along the original surface of the ravine at its top edge near its beginning point. It included handmade brick, some oyster shell mortar, pantile fragments and a couple of nails. The paucity of nails is quite unusual. Every other 17th-century site we have investigated yields many nails so the few found here was noticeable. Examination of the brick shows that it is the same type as was used in the State House. And the pan tile is identical to that found at the State House and St. John’s. Some of these materials are seen here.

Brick and Roof Tile from the 1676 Prison.

Brick and Roof Tile from the 1676 Prison.

Significantly, this find is in the general area where the prison was indicated on the 1778 map. Its construction was part of the same contract with John Quigley to build the State House. Hence, the similarity of the architectural materials makes good sense because it was done by the same builder.

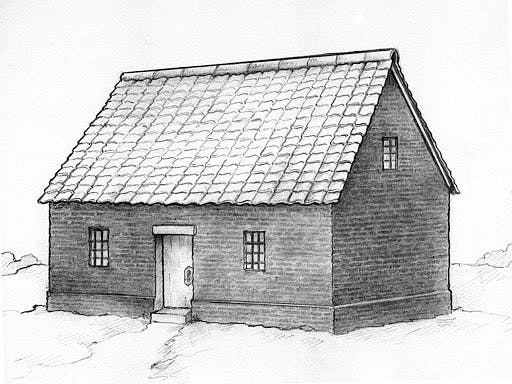

So what was the brick prison like? Fortunately, it is one of only two buildings in St. Mary’s for which we have detailed architectural specifications; the other is the State House. In June of 1674, Captain John Quigley agreed to be paid 330,000 pounds of tobacco to build both brick structures and to complete the work by October of 1676. This was a huge amount of money and it was the first major infrastructure investment made by the colonial government. The contract section about the prison read

“…the said Prison to be Substancially built of Stone or brick laid in lime & sand twenty four foote long in the Cleer within & fifteen foote wide within Nine foote high to the plate and a particon in the midle with a floore below paved with flatt Stone or Brick and another aboue laid with planck and Covered with tile laid in morter with Sufficient locks barrs and windowes fitt for a prison” (Archives of Maryland 2: 406)

As the building was being completed in May of 1676, Quigley asked the Legislature to specify the types of windows they wanted in the prison. This hints that Quigley first concentrated on the State House and only when it was near completion did he turn to the much smaller prison. Legislators gave the following answer:

“This house upon debate thereof doe think fitt tht Lower house the Windowes be of Wood with Substanciall Iron barres and tht the wood of the frame of the Windowes be layd in Oyle, alsoe made Soe large as to lye into the brick worke two foot and a half of a Side both above and below the Windowes to be twenty Inches Wide and thirty Inchs high Three Jron Barres Upright and two a thwart the upright Jron barres to be Jnch and quartr Square and To be Wrought into the two thwart Barres and tht there be two Windowes belowe and one Windowe of Wood above.” (Archives of Maryland 2: 487).

Based upon the architectural specifications for the building, Architectural historian H. Chandlee Forman created a drawing of how the prison may have looked. It appeared in his famous Jamestown and St. Mary’s: Buried Cities of Romance (1938). The picture here is a slight modification of Forman’s original drawing.

The 1676 Prison or Jail as it may have appeared in the late seventeenth century.

The 1676 Prison or Jail as it may have appeared in the late seventeenth century.

The archaeological findings in 1994 match closely the debris one would predict to find from the prison, based on the architecture-related documents. The similarity of the brick and pantile found at both the State House and Prison is a clue that the constructions were related and occurred during the same general time period. The paucity of nails is understandable because the building had relatively few nails given that the walls and roof were masonry. Nearly every other structure in the city had walls and roofs of clapboard and/or shingle, requiring many nails. Given all the evidence, we are confident that these artifacts were from the 1676 Prison.

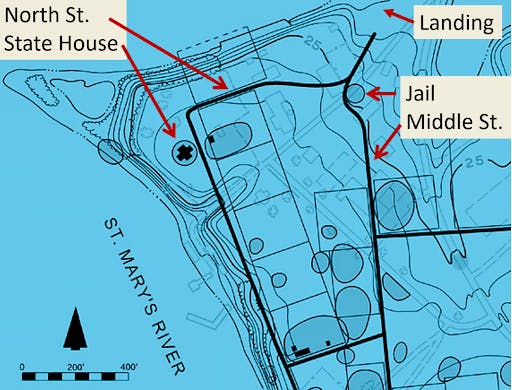

In doing the archaeology, we observed that the rubble was most intense at the top of the ravine near its eastern side and did not extend down into the bottom of the depression. This distribution suggests that the structure stood above the beginning of the ravine, on its east side. The picture below gives my best guess as to its original location.

Likely location of the 1676 Prison in relation to modern features, based on archaeology. Kent Hall is on the left and the old tennis court behind and to the right of the jail.

Likely location of the 1676 Prison in relation to modern features, based on archaeology. Kent Hall is on the left and the old tennis court behind and to the right of the jail.

Subsequent archaeology elsewhere has found fence and ditch features that more precisely define Middle Street and its route. It ran from the Town Center to the prison and then led to the main boat landing for the city. This data indicates that the street was intentionally pointed at the brick prison, a significant feature of the unique baroque plan for the city. It curved to the left as it approached the structure and then ran down the ravine to the landing. Thus, the old ravine we discovered served as the end point of one of the principal streets in St. Mary’s. This also helps us locate another route in the city, North Street. It is not well documented but ran between the State House and Prison. The available data suggests that it also used the same ravine to reach the landing area but entered it on the western side. Having this information has allowed us to revise and improve the map of Maryland’s first capital. These key elements of the original north end of the City landscape are seen mapped below.

Map of the North end of St. Mary’s City c. 1685. Based on the archaeological and historical evidence, it is overlaid on a map of modern features.

Map of the North end of St. Mary’s City c. 1685. Based on the archaeological and historical evidence, it is overlaid on a map of modern features.

We cannot say if any traces of the foundation have survived the many disturbances in this area, but we are now far more certain of where Maryland’s first brick prison stood. Any future disturbance in the vicinity should be carefully inspected for any remnants of this unique structure.

Although the 17th-century residents of St. Mary’s City used the term “prison” for it, this can lead to some misunderstand by modern readers. Justice in the 17th-century colonies tended to be swift and often harsh by our standards. People were not sentenced to long terms of incarceration in early Maryland. The building is more accurately called a jail where people were held prior to and during a trial and sentencing. Fines would be the most lenient penalty one could receive, but whipping, boring of the tongue, branding, cutting off an ear and other punishments were given out, along with an occasional execution by hanging. However, the most brutal form of “hanging, drawing and quartering” of a prisoner, as occurred in Virginia, was never applied in Maryland.

Around the jail there were also several tools of punishment. These include a pillory and stocks, and on the shore of St. John’s pond a dunking stool. One document tells that Garrett Van Sweringen was paid to build these for the government. And on the opposite shore of St. John’s pond, where the student center and Margaret Brent Hall now stand, was the gallows for the colony, readily visible from the prison. St. Mary’s was not only the center of government but also the seat of justice in Maryland.

A 17th-century Dunking Stool in use. From https://fineartamerica.com/featured/the-ducking-stool-originated-everett.html

A 17th-century Dunking Stool in use. From https://fineartamerica.com/featured/the-ducking-stool-originated-everett.html

There were several attempts to construct a jail at St. Mary’s before 1674, but these apparently failed. The brick “Prison” was the first one to actually be built in Maryland. Prior to this, the Sheriff would have to hold a prisoner in their home or lock them in a room at an ordinary or a convenient outbuilding. Construction of the brick prison was an important step in the maturing of Maryland’s society and its legal apparatus. Indeed, the Prison was a significant symbol of crime, justice and punishment in the colony. For that reason, it was integrated into the city plan and served as a visible node of the street system.

This very valuable discovery was a surprise, and it came about purely by chance. It is a striking example of the need for constant vigilance of the lands where Maryland’s first city once stood. We are grateful that the College staff took the time to notified us that something had been uncovered at Kent Hall. Otherwise, we might never have found the evidence of this notable structure nor deciphered the original 17th-century landscape of this part of the city. Digging for whatever reason always carries the potential to uncover remarkable things and it is essential that we are continually watchful for new clues to be revealed.

About the Author

Dr. Miller is a Historical Archaeologist who received a B. A. degree in Anthropology from the University of Arkansas. He subsequently received an M.A. and Ph.D. in Anthropology from Michigan State University with a specialization in historic sites archaeology. Dr. Miller began his time with HSMC in 1972 when he was hired as an archaeological excavator. Miller has spent much of his career exploring 17th-century sites and the conversion of those into public exhibits, both in galleries and as full reconstructions. In January 2020, Dr. Miller was awarded the J.C. Harrington Medal in Historical Archaeology in recognition of a lifetime of contributions to the field.