Pots have been made in Maryland for over two millennia by Maryland Indians. These were hand formed using local clays, strengthened by adding grit or broken up shell or other materials and sometimes decorated, sometimes not. We will never know who the first individual was who made these pots, but based on Eastern North American practices, it was probably a woman.

When the English settlers arrived in 1634, they brought all the manufactures goods they needed and relied upon imports afterward. In an economy focused almost exclusively upon tobacco production for export, there was little incentive to make things that could be more readily and cheaply acquired from the next Tobacco Fleet. But one merchant named Robert Slye intended to change that. Slye was one of the wealthiest persons in Maryland in the third quarter of the century and apparently saw some craft production as another means of expanding his business. Consequently, he acquired an indentured servant with potting skills in 1661. The servant was Morgan Jones and an examination of name distributions over Britain strongly suggests that Jones was from Wales. He made pots at Slye’s Bushwood plantation, located about 25 miles from St. Mary’s and he became the first potter in colonial Maryland. Slye’s plantation house and other structures were located somewhere in the vicinity where the magnificent Ocean Hall now stands. Ocean Hall was meticulously restored by Dr. Jamie Boyd and he published a valuable book on this decades long effort to save one of the oldest surviving houses in Maryland. Tree Ring analysis shows that Ocean Hall was built in the early 18th century.

Ocean Hall is in the general area where Morgan Jones’s first Potthouse stood in the 1660s.

Ocean Hall is in the general area where Morgan Jones’s first Potthouse stood in the 1660s.

Jones’s indentured probably lasted three to five years and he must have produced considerable pottery over that time. In the estate inventory made at the time of Slye’s death in 1671, “a Potthouse” is described but no contents are listed. However, elsewhere in the inventory there are a number of butter pots and milk pans and 431 earthenware porringers, a huge number that may represent Jones’s work. When the indenture ended, the evidence indicates that Jones moved to the southern shore of the Potomac in Westmoreland County, Virginia. A 1669 document tells that Moran Jones agreed to assign to merchant John Quigley “. . . my share of ye earthenware that I have made this year at ye Potthouse at Mr. Quigley’s Plantation and also my share of ware which I shall by God’s Grace make this present year upon ye said plantation and all my share of lead ovens that I have there in my possession . . .”. This is the same John Quigley who built the 1676 State House at St. Mary’s City and had some business relations with Garrett Van Sweringen. St. Mary’s City would have been one likely market for these wares.

In August of 1677, Jones made an agreement to partner with a Dennis White for the “making and selling of Earthen ware…” during a period of five years. White died at the end of the year and it is uncertain how long production continued afterward. By 1681, Jones briefly moved to Lower Norfolk County Virginia but relocated to Dorchester County, Maryland, were he became a tobacco planter. He died there ten years later. His inventory includes “a parcel of earthenware” valued at £2. Given how cheaply earthenware is generally appraised in other inventories, this indicates it must have been a large number of vessels and strongly suggesting that Jones was still making pottery, at least on a part-time basis.

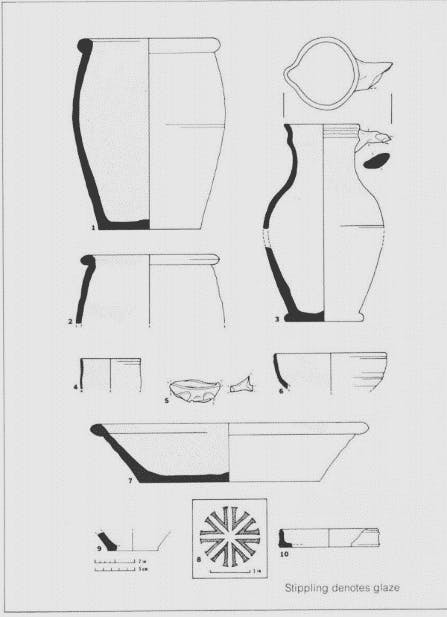

From then onward, Morgan Jones was completely forgotten to history, until an archaeological discovery in 1973. In that year, a pottery kiln was found at a place called Glebe Harbor in Westmoreland County, Virginia. Excavation and analysis by William Kelso and Edward Chappell indicated that it was the kiln built by Morgan Jones and Dennis White in 1677. The kiln seen below probably was similar to that Jones built in 1661 in Maryland. Study of the remains indicates that it had an oval plan and was capped with a dome made of brick. The trenches extending from the circle were firing channels and stoking pits. A small opening must have existed at ground level to allow the pots to be placed and then removed after firing. This opening would have been shut with brick and probably clay prior to the firing. The archaeologists found large quantities of wasters, which are pots that cracked or were otherwise flawed and discarded. Study of them gave the first indication of the wares made by Morgan Jones. Drawings of some of these vessels were published in 1974, as seen here.

The Glebe Harbor pottery kiln of Morgan Jones under excavation in 1973 (Photo Courtesy of the Virginia Department of Historical Resources).

The Glebe Harbor pottery kiln of Morgan Jones under excavation in 1973 (Photo Courtesy of the Virginia Department of Historical Resources).

Some of the Pottery shapes made by Morgan Jones and recovered from the kiln site. From Kelso, William, and Edward Chappell 1974, Excavation of a Seventeenth-Century Pottery Kiln at Glebe Harbor, Westmoreland County, Virginia. Historical Archaeology Volume 6:53-63.

Some of the Pottery shapes made by Morgan Jones and recovered from the kiln site. From Kelso, William, and Edward Chappell 1974, Excavation of a Seventeenth-Century Pottery Kiln at Glebe Harbor, Westmoreland County, Virginia. Historical Archaeology Volume 6:53-63.

Given this history, it seemed possible that we would find Morgan Jones pottery at St. Mary’s City and this proved to be the case. In my analysis of the pottery recovered from the St. John’s site, a number of fragments seemed to match the description of the pottery found at the kiln site. To verify this, a trip to the former the Virginia Research Center for Archaeology in Williamsburg gave me the opportunity to compare the St. John’s specimens with the kiln wasters. They were a match. Morgan Jones was marketing his wares to St. Mary’s City.

While St. John’s yielded many fragments of vessels, a chance discovery yielded the first nearly complete vessel. It was found while the College dug a trench for a television cable going into the old Ann Arundel Hall in 1977. The trench hit a 17th-century pit in which was an upside-down broken pot. It is seen here as it was uncovered. Inside, we found a stack of chicken eggs that were discussed in Clues # 16.

The Morgan Jones Pitcher in the pit as it was uncovered. Photo by Garry Wheeler Stone.

The Morgan Jones Pitcher in the pit as it was uncovered. Photo by Garry Wheeler Stone.

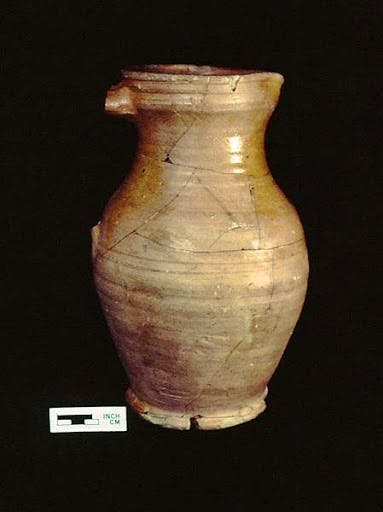

The vessel turned out to be a Morgan Jones pitcher, and all the pieces except the handle were present. I was able to reconstruct the vessel as you can see. The handle had broken off at some earlier time but they continued to use the pitcher. This is indicated by wear on the broken edges. It seems that it was used as a kitchen slop jar for some time before being cast into the pit.

The reassembled Morgan Jones Pitcher. Photo by Donald Winter.

The reassembled Morgan Jones Pitcher. Photo by Donald Winter.

Since then, excavations have found hundreds of pieces of Morgan Jones’s pottery in a variety of forms including two more nearly complete pitchers, (seen here), cups, bowls, baking dishes, and dairying vessels like milk pans and butter pots. A few of these are also shown below.

One attribute of Jones’s work is its uneven quality. Kelso and Chappell found many failed or misshaped pots at the kiln site, but this is typical of wasters, and they noted that one cannot fairly judge the quality of a potter by the wasters. Subsequent archaeology on many sites now shows us the nature of the vessels Jones sold to customers. They tend to be from fair to good quality. Although most are adequately fired, this is uneven in some vessels and the lead glaze tends to be applied almost haphazardly on a number of vessels. You can see this variation on the three complete pitchers. But the shapes are consistent, showing he was striving for a specific size and shape of vessel. Inadequate kiln design may have been a major problem for Jones.

The three nearly complete Morgan Jones Pitchers from St. Mary’s City

The three nearly complete Morgan Jones Pitchers from St. Mary’s City A small baking pan about six inches in diameter made by Morgan Jones.

A small baking pan about six inches in diameter made by Morgan Jones. A Morgan Jones Milk Pan used in dairying and in the kitchen.

A Morgan Jones Milk Pan used in dairying and in the kitchen.

All the Jones pots were made using a wheel, which was the standard European method of pot production during this period and long before. The potter determines the shape and size of the intended vessel and they can impart unique features on pots that mark their work. These can be both intentional and unintentional. One intentional action of Jones was to sometimes press a “maker’s mark” into the soft clay. It was a star-burst and can be seen at the bottom of the drawing of the vessels shown above.

But Jones also left an inadvertent mark. In making the pitchers, he applied the handle at the top and smoothed the clay, but at the bottom he pressed the clay against the pot using his thumbs. This often left his fingerprints in the soft clay, as seen in this picture. It is a reliable indicator of a Morgan Jones pitcher.

Morgan Jones’s Thumbprints on a vessel found at St. Mary’s City.

Morgan Jones’s Thumbprints on a vessel found at St. Mary’s City.

Maryland’s first colonial potter made utility wares and not fine ceramics. The vessels he produced were for the kitchen, dairy, and for drinking. And his business was successful for his pots were widely distributed, being found on numerous sites at St. Mary’s City, elsewhere along the Potomac and Patuxent Rivers, occasionally on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, and even at Jamestown. Jones served the local markets in the Chesapeake and met the ceramic needs of regular planters. Aside from blacksmithing, coppering, and housewrights, he represents the earliest effort at craft production in the upper Chesapeake. Several other potters worked in the Jamestown area in the post-1660 period, but Morgan Jones’s kiln is the only one that has been fully excavated. And because he is documented and his products identifiable, his pottery has become an invaluable dating tool for archaeologists throughout the Chesapeake, indicating a 1661-1691 time of habitation.

Morgan Jones’s first kiln in Maryland has not been found. However, in the late 1970’s this author retrieved a handmade colonial brick in a plowed field near Ocean Hall. On it was a semi-circular coating of a lead glaze. The Glebe Harbor kiln site milk pans had glaze flow marks on them indicating that they were stacked several vessels high in a staggered fashion so that the rims of inverted vessels rested on the rims of upturned vessels. The curved glaze mark on the brick roughly matched the curve of a milk pan rim and I believe this brick is the only artifact yet found that can be linked to the first pottery kiln in Maryland. It remains a hope that this unique and significant site can someday be discovered by archaeologists.

About the Author

Dr. Miller is a Historical Archaeologist who received a B. A. degree in Anthropology from the University of Arkansas. He subsequently received an M.A. and Ph.D. in Anthropology from Michigan State University with a specialization in historic sites archaeology. Dr. Miller began his time with HSMC in 1972 when he was hired as an archaeological excavator. Miller has spent much of his career exploring 17th-century sites and the conversion of those into public exhibits, both in galleries and as full reconstructions. In January 2020, Dr. Miller was awarded the J.C. Harrington Medal in Historical Archaeology in recognition of a lifetime of contributions to the field.