Archaeology at the St. John ‘s site revolutionized our understanding of life in early Maryland and recovered well over a million artifacts. Perhaps the most unique of all found by Ruth Mitchell’s team in 2004 was a thin piece of lead. Seemingly merely another artifact, it was put in the bag with other items and taken to the lab. There lab assistant Kelly Brookhart (McNamara) was washing the artifacts and as she cleaned the lead object, noticed some type of impression on it. We occasionally find pieces of lead cloth seals that were affixed to cloth to certify their origin and quality or tariffs. These are usually two-sided lead circles connected by a lead tag that were crimped down over one corner of the cloth. Here are a few of the Cloth Seals we have found at St. Mary’s City.

Lead Cloth Seals found at St. Mary’s City. Photo by Donald Winter.

Lead Cloth Seals found at St. Mary’s City. Photo by Donald Winter.

Kelly probably initially thought it was a fragment of another cloth seal. However, as more dirt was washed away, another possibility arose. She brought it to lab supervisor Donald Winter who in turn showed it to curator Silas Hurry. Using raking light under a low power microscope, they saw that it was impressed with a shield that looked familiar. This is the object.

The St. John’s artifact (ST1-23-443B/AX). Photo by Donald Winter.

The St. John’s artifact (ST1-23-443B/AX). Photo by Donald Winter.

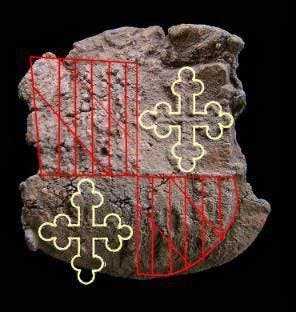

Although the lead had undergone considerable decay, conservation treatment removed some of the corrosion. It became clear that this object displayed a shield divided into four parts with the right side better preserved. Closeup pictures of those sides are seen below.

Close up views of the best-preserved sections of the artifact. Photo by Donald Winter.

Close up views of the best-preserved sections of the artifact. Photo by Donald Winter.

The top right quadrant is a cross-botany and the bottom right is a series of lines described in heraldic language as a paly of six pieces bent countercharged. Despite the corrosion, close examination of the left side shows that the top is another paly and the bottom is a cross botany. Without question, this is the Shield of Arms of the Calvert Family, which is also a central element in the Great Seal of Maryland. Overlaying the full picture with the outlines of the Calvert shield produces the picture below. The 1648 Great Seal is shown for comparison.

The St. John’s lead artifact with the Calvert Shield outlined and the Great Seal of Maryland. Artifact Photo by Donald Winter, Great Seal by Henry Miller, Courtesy of the Maryland State Archives.

The St. John’s lead artifact with the Calvert Shield outlined and the Great Seal of Maryland. Artifact Photo by Donald Winter, Great Seal by Henry Miller, Courtesy of the Maryland State Archives.

What is the Calvert Coat of Arms doing on a tiny piece of lead? While similar to cloth seals, it is a bit larger than most. Coats of Arms of some king and especially of cities are found on cloth lead seals to denote the place of origin, certification of quality and later to show a tariff had been paid. These are all for commercial purposes. I can find no evidence that the Calverts ever employed seals to certify or receive tariffs on goods coming to Maryland or affixed a Maryland seal on hogsheads of tobacco coming from Maryland. That would have required a large administrative effort that was beyond the capacity of Lord Baltimore. Also, most cloth seals are two parts, connected by a strip of lead. One side has a rivet on the back of one and a hole is present on the opposite half into which the rivet will be inserted. This is then pressed flat with a vicelike tool that impresses the symbols or numbers into the lead. Sometimes the weave of the cloth or strap that is between the two disks will also be impressed on the inside of the seal due to the pressure. The back side of the St. John’s artifact is flat with no trace of a rivet and shows no impressions of cloth. It could have been made as a four-part seal but those were rarely used in England although more common in Europe. In any case, given the lack of historical evidence, it seems improbable that this object with the Maryland seal was employed for commercial or financial purposes. So the question remains why is there a lead object with the Calvert shield on it?.

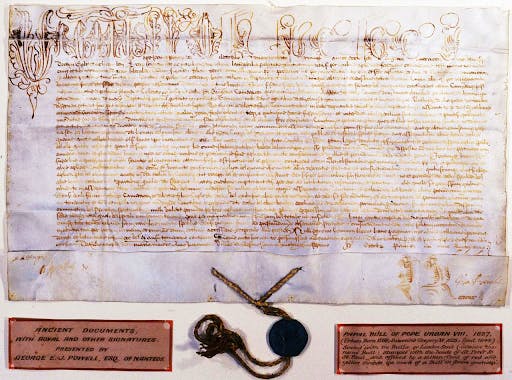

It is proposed here that it is a special seal known as a bulla that served as an official signature. The word originates in Latin as bubble but in medieval times came to mean a round seal. Bullae are lead seals that have long had royal and especially papal connotations. A seal in lead instead of the easily breakable wax carried greater significance and was the official signature of the authorizing official. Although known in Roman times, bulla continued in use in the Byzantine Empire and were gradually readopted in Europe during the medieval period. But the bulla is most well-known for its use by the Pope, which began in the 600s. The bulla certifies official pronouncement of the Pope, which became known as Papal Bulls for the bulla which authenticates them. These bulls are legal documents that deal with official church business and the bulla is recognized as the formal signature of the pope. They hang from the parchment document attached by string, silk, or hemp rope that run through a channel in the bulla. Here is a 1637 example of a Papal Bull.

Papal Bull of Pope Urban VIII with the lead bulla attached with a cord. It dates to 1637. http://www.aber.ac.uk/museum/collections/index.shtml . Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1115943

Papal Bull of Pope Urban VIII with the lead bulla attached with a cord. It dates to 1637. http://www.aber.ac.uk/museum/collections/index.shtml . Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1115943

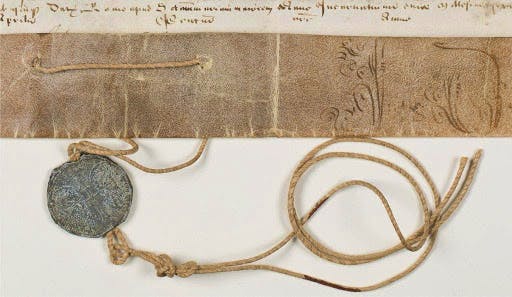

Here is another good example of a Papal Bull, dating from 1618, with a close up view of how the bulla is attached.

Papal Bull of Pope Paul V, 1618 https://blogs.shu.edu/archives/digital-exhibitions/papal-bull-of-pope-paul-v-1618/

Papal Bull of Pope Paul V, 1618 https://blogs.shu.edu/archives/digital-exhibitions/papal-bull-of-pope-paul-v-1618/

They were also used by high church officials such as Cardinals and Bishops in their official business on the Continent. Here is the bulla of a 17th-century Italian bishop. So the Continental use of bullae during the period is well confirmed.

17th-century Italian Bulla

17th-century Italian Bulla

On the other hand, they were exceptionally rare in Post-Medieval Britain. There are hundreds of bullae on documents in British collections but virtually all are of European origin and of Medieval date. In the British National Archives at Kew there are hundreds of thousands of documents bearing seals from the Medieval and Post-Medieval eras and yet virtually all those of British origin are made of wax. Metal seals are so rare that two exceptions discovered in the Kew archive merited a special report published in 2005. They are both found on tax records that date to 1571 and 1577. Both are of a William Strode of Devonshire. He appears to have been the only Englishman to have made his personal seal of lead. This is one of his seals, attached to the tax record with tags of parchment.

Very rare Lead Seal of William Strode, created in 1577 in Devonshire. From Elizabeth A. New and Mark Forrest, Impressed in Metal: The Seals of a Devon Tax Collector, The Antiquaries Journal 2005, 85(1): 366-373. Photo is courtesy of the British National Archives.

Very rare Lead Seal of William Strode, created in 1577 in Devonshire. From Elizabeth A. New and Mark Forrest, Impressed in Metal: The Seals of a Devon Tax Collector, The Antiquaries Journal 2005, 85(1): 366-373. Photo is courtesy of the British National Archives.

The authors also provide some important information about how it was made. Papal bulla blanks are cast so that a channel runs through the middle into which cord, silk or rope can be later inserted. The warmed lead is then placed into a vice-grip type device that holds an upper and lower seal matrix. When pressure is applied, the seals are impressed onto the lead, and the connecting cord is secured within the bulla by the pressure. Strode used a different method. He took a thin strip of lead, bent it in half, placed the parchment tag inside, and then used some type of vice grip-like tool to impress the seals on each side and secure the parchment tag between the lead sections. The Calvert bulla piece is only marked on one side and it may have been made using some variant of the Strode method, although there are other possibilities. How it was affixed must remain unresolved because the opposite half broke off and has not been found.

As noted, Strode appears to have been a highly atypical Englishman. The authors examined records and catalogues of thousands of other seals and found no other British examples struck in metal. The only exceptions are a few superb gold Royal bullae used to certify international treaties. Additional evidence for their rarity comes from the Portable Antiquities Scheme that collects data on objects found by metal detectorist from around Britain. Of the 487 bullea reported thus far, nearly all are of pre-English Reformation date and most are from papal bulls. There is a single 17th-century exception. It is a bulla found in Dorset with the mark of Marc Antonio Giustiani, Doge [Duke] of the Republic of Venice, who ruled from 1684 to 1689 and thus is of European origin. If individuals had used lead seals at least occasionally as their official signature, some specimens should have been recovered by metal detectorist. For comparison, a similar lead artifact cloth seals are not rare. The Antiquities Scheme reports 4309 of these have been recorded. Lead bulla are simply not an element of 17th-century British material culture.

There is no question that bullae were recognized as an especially authoritative means of “signing” a document, especially for Catholics. Indeed, it was a prestigious device to show approbation. Given that meaning, it seems reasonable to suggest that this object had a similar purpose. Long associated with European royalty, especially in the Holy Roman Empire, and leaders of the Church, the person most likely to have used such a device is Maryland’s Proprietor Cecil Calvert, the Lord Baltimore. It would have been affixed to documents of special significance. They would include official proclamations about the colony, his proposed laws, formal certification of the laws after the legislature revised them, and other administrative affairs requiring his explicit authorization. As Maryland’s “king”, all laws had to receive his explicit approval. The Assembly would receive and/or be aware of the varied documents issued by Lord Baltimore, as would members of the Council and other officials.

It is also notable that inspection of the other surviving wax signet seals of the Calvert family indicates that this lead specimen is larger and must have been made with a different seal matrix. For legal and personal documents in England, Cecil Calvert used the seal seen below, not the full coat of arms as seen on the Maryland Great Seal. This one is on a 1641 document in a Wiltshire archive, and there are other documents with the same seal and Calvert’s signature. It is also notable that George Calvert used a similar signet in the late 1620s.

Cecil Calvert’s Personal Seal in Wax on a 1641 Legal Document. Courtesy of the Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre, Chippenham, Wiltshire.

Cecil Calvert’s Personal Seal in Wax on a 1641 Legal Document. Courtesy of the Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre, Chippenham, Wiltshire.

While Governor of Maryland, Charles Calvert used a similar seal although on a different matrix. This is seen on his personal correspondence, here attached to a 1664 letter to his father. The letter was written at St. John’s and is now in the Calvert Papers.

Governor Charles Calvert Wax Seal from 1664. The Calvert Papers, No. 1063. Courtesy of the Maryland Center of History and Culture.

Governor Charles Calvert Wax Seal from 1664. The Calvert Papers, No. 1063. Courtesy of the Maryland Center of History and Culture.

However, Leonard Calvert did use a signet with the full Maryland crest after becoming governor. It is seen here on a letter in the Calvert Papers. Written to Calvert’s partner Richard Lechford, it is dated 6 May 1638. Prior to becoming governor, Leonard used a different seal on his correspondence to Lechford. All are wax seals.

Governor Leonard Calvert’s Seal of 1638 on a letter to Richard Lechford. Courtesy of the Maryland Center for History and Culture.

Governor Leonard Calvert’s Seal of 1638 on a letter to Richard Lechford. Courtesy of the Maryland Center for History and Culture.

Use of the full Calvert (and Maryland) shield as a signet seal seems to have been early. But one made of lead instead of wax is highly unusual. Given the understood meaning of a lead seal as a ruler’s authorizing “signature” it, strongly points to Cecil Calvert, the Lord Baltimore and Maryland’s proprietor as the issuer. Unfortunately, we cannot date the artifact other than to the general occupation period of St. John’s (1638-c.15). It was found in the plowed soil zone. However, there are two residents at the site who are mostly likely to have received and/or stored such an item: Secretary of State John Lewger (1637-1647), and Governor Charles Calvert (1662-1667). Lewger kept most of the colony’s legal records and received instructions and official documents from Lord Baltimore. The pillaging of his house at St. John’s in 1645 by Richard Ingle’s men resulted in the loss of most of Maryland’s early records; and that is one possible time when documents were destroyed and seals would be separated from them.

If the lead Maryland seal was frequently issued in the colony, one would expect others to have been recovered during the very extensive excavations at the Leonard Calvert House, which served as Maryland’s first official statehouse, at other Town Center sites, or the government office that later became the Van Sweringen site. But no others have been found and it seems improbable that this was a regular practice that continued over many years. While speculative, it is suggested that this was something Lord Baltimore attempted early in his reign, but subsequently abandoned it and returned to the traditional wax for his later seals, as surviving examples attest.

But the lingering question is why he would have adopted such a practice in the first place? He was clearly following a European and Catholic practice, not an English one. Did the more permanent nature of a lead seal influence the decision. Did he see it as conveying more authority for special documents, as it did in Europe? Alternatively, could it have been a subtle way to materially signal his Catholic identity by using a method long associated with the papacy, an effort that ceased when he had to appoint a Protestant governor in 1648? It is impossible to answer such questions, but it is another clue that Lord Baltimore was doing things differently.

One thing is certain. This is a very rare artifact. If the bulla interpretation is correct, it is the only English bulla found in America and is probably the only 17th-century example from Britain itself. And there is no question that it is the oldest archaeological specimen ever recovered that displays the Calvert shield, symbols still seen today on the flag of Maryland. As such, it is truly a remarkable artifact of exceptional significance.

About the Author

Dr. Miller is a Historical Archaeologist who received a B. A. degree in Anthropology from the University of Arkansas. He subsequently received an M.A. and Ph.D. in Anthropology from Michigan State University with a specialization in historic sites archaeology. Dr. Miller began his time with HSMC in 1972 when he was hired as an archaeological excavator. Miller has spent much of his career exploring 17th-century sites and the conversion of those into public exhibits, both in galleries and as full reconstructions. In January 2020, Dr. Miller was awarded the J.C. Harrington Medal in Historical Archaeology in recognition of a lifetime of contributions to the field.