When I began exploring the diet of early Marylanders, one important source of information was the types of foods they would have known in England. There is much documentary and archaeological data about that. The English primarily ate wheat and barley, a variety of vegetables such as beans and cabbage, and consumed beef, pork and mutton, along with poultry. Wild animals, aside from fish, made up only a limited element of the diet. Given this, it was anticipated that the Maryland colonists would attempt to reestablish as much of their traditional foodways as possible.

As was the case then and is the same today, flocks of sheep are commonly seen on the landscapes of Britain and Ireland. Dishes such as Shepherd’s pie, mutton stew, roasted lamb or even lamb burgers are regularly found on pub and restaurant menus. Sheep have been a key element in British cuisine and the economy for about 6000 years, beginning in the Neolithic period.

A common scene of a Sheep-dotted British Landscape

A common scene of a Sheep-dotted British Landscape

In early Maryland, animal bones from sites show that cattle, pigs and chickens thrived and these became major elements of the colonial diet. Largely missing from the early deposits are sheep. But bat first, this seemed to not be the case. During the 1973 excavations at the St. John’s site, a small pit was uncovered in the backyard of the house. Its excavations revealed the remains of an adult sheep as seen here. They were clearly present in early Maryland. The initial speculation by some of the crew was that it might have been a pet, as it was treated in death like a dog or cat would often be today. As analysis began, this proved to be unlikely.

The Sheep Burial found in the backyard of St. John’s in 1973.

The Sheep Burial found in the backyard of St. John’s in 1973.

The animal was an adult ewe between 5 and 10 years of age based on tooth wear. At the time of her death, she was pregnant with two lambs. Someone buried her in a shallow hole about 1.3 feet deep. Plowing later damaged the skull and removed some of the hoof bones. Most of the hind portion of the ewe was missing at the time of burial, aside from a tibia (the long bone seen on the right side in the picture). Significantly, there are no cut marks on any of the bones, demonstrating that she was not butchered and partially consumed by people. In addition to the missing hindquarters, the remains of the lambs were scattered about the abdominal area and the skull of one is missing. The lamb remains are seen below.

The remains of the two unborn lambs in the St. John’s burial

The remains of the two unborn lambs in the St. John’s burial

There were virtually no artifacts in the grave fill. Excavators found one fragment of a case bottle, a brick fragment identical to that used in the original St. John’s chimney, a Sheepshead fish bone, two fragments of a cattle tooth and one pig tooth. This area later became the main garbage dump for St. John’s and the few artifacts indicate that this is an early burial. When excavations resumed at St. john’s in the early 21st century, another buried sheep was found not far from the ewe discovered in 1973. It’s skeleton is more complete than that of the ewe but if was probably buried around the same time because there is also a paucity of artifacts in its fill. It is seen here, and we thus found two adult sheep buried about 25 feet from the back side of the St. John’s House.

The second sheep burial found at St. Johns in 2003.

The second sheep burial found at St. Johns in 2003.

Analysis of the two lambs shows that they were within a month of being born. One was larger than the other and this may indicate they were male and female lambs. The general lambing time in the 17th-century was between February and April, so the ewe was probably killed in January or February.

What type of sheep were they? There were no breeds at the time, since breeding of livestock began in the 19th century. Only broad regional varieties existed in the 17th century. The first clue is that none of the animals at St. John’s had horns. Instead, small nodules or scurs are seen on the skulls where horns would have been. This feature is also present on the lamb skull, indicating these were hornless sheep. Size is another important clue. Measuring the long bones allowed me to calculate that she stood about 25 inches high at the withers or shoulder. This fact tells that the animal was larger than the more archaic Scottish sheep, she was smaller than the long wooled Cotswold types, and not a Linton type sheep because she had no horns. These clues point to her being a Heath-type sheep, one of the most common types in 17th-century England, found in the South, West and Midlands. The closest breed to these early animal stoday is the Southdown sheep that has a white face and medium wool as seen here. The Southdown is considered good at lambing, docile and adaptable to different settings. It is most probable that the St. John’s animals originally came from Southern England and may have been shipped from London.

Modern Southdown Sheep, one of the oldest English Breeds and probably similar in appearance to the Sheep found at St. John’s.

Modern Southdown Sheep, one of the oldest English Breeds and probably similar in appearance to the Sheep found at St. John’s.

Given the early date of the burials, these sheep are probably part of a flock given to Lord Baltimore by Virginia’s Secretary of State Richard Kemp in 1638. As such, they were some of if not the first sheep in the colony. John Lewger was responsible for them but there were serious problems. Lewger reported to Lord Baltimore in 1644 that of the eleven remaining sheep in the flock, four had been “Killed by Wolves” the previous year. It is very probable that the two sheep burials were part of Kemp’s gift and the ewe may even be one of the sheep Lewger is referring to in his report.

Why were they buried and not eaten? It is of significance that both burials were within the fenced backyard of St. John’s, only 25 to 30 feet from the house. The ewe was ravaged by predators and perhaps the remaining meat was not considered edible or had spoiled. The other sheep is more intact but it too was not consumed and must have been considered inedible by the time it was found. Why not just throw the carcasses into a ravine or out in the woods? I speculated that there must have been some reason to go to the trouble of burial so near the house but was unsure of precisely why. The answer was finally provided during a tour I was giving of the St. John’s site in 2012. The ewe’s skeleton is on display there and I told her story and said it remained a mystery why someone went to the trouble to bury her and the other sheep. One person in the group was from England and a sheep raiser. He said “I can tell you why. If your dogs ever get a taste for mutton or lamb, they become useless because they go after the animals. Then you have to get rid of them. You bury the animal so the dogs cannot get at the carcass.” We know there were dogs at the site because their teeth have been recovered and chew marks are observed on bones. Coming from a person with direct experience, this seems to be a valid explanation for the burials. Someone at St. John’s obviously had familiarity with sheep raising.

Nevertheless, raising sheep in the early Chesapeake was quite challenging. Unlike England, It was mostly a forest covered land with few open patches of grass. Pastures had to be created. Even worse were predators. A traveler to Virginia in 1676, Thomas Glover, wrote that “As to sheep, they keep but few, being discouraged by wolves, which are all over the Country and do much mischief among the flocks.” John Lewger’s statement confirms this was true for Maryland as well. Bounties were place on wolves and their populations were gradually reduced in the longest settled areas by the late 1600s. Bobcats and foxes could also prey upon young lambs. In contrast, cattle and swine could better defend themselves and they were allowed to run free over the fields and forests, feeding themselves. Little labor was needed to maintain them. A French traveler Durand of Dauphine came to the Chesapeake in 1687 confirms this when he wrote regarding livestock, that “…it costs nothing to keep or feed them, they do not know what it is to mow hay, Their animals all graze in the woods or on untilled pasture of their plantations, where they seek shelter nightly rather by instinct than from any care given them”. Sheep, on the other hand, required attention and care for their protection. Given the labor shortage on the new frontier, growing tobacco was a far more lucrative endeavor than spending time tending sheep. And essentials such as clothing were almost totally imported from England.

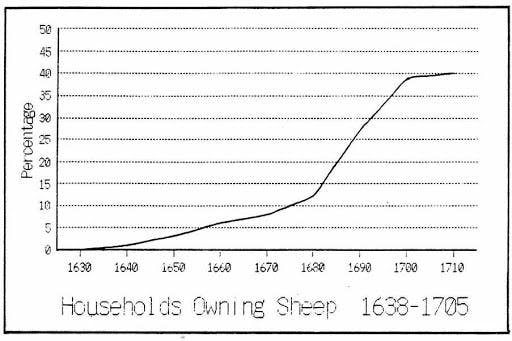

Analysis of food bones from numerous sites show that that initial impression about sheep in the colony were wrong. They were actually quite rare during the first decades and lamb and mutton made up a tiny proportion of the meat diet in the early Chesapeake. From six pre-1660 sites, no sheep are present on three of them and sheep bones make up less than 1% of the bone on the others. At St. John’s during this time, sheep account for only 0.8% of the bone and just over 1% of the meat. Sheep were not successfully transferred to early Maryland. This can also be seen in household inventories. Several hundred St. Mary’s County inventories show the rarity of sheep in the early decades (See Figure below). It is only in the last quarter of the century that sheep become more common on plantations. The war waged against wolves had proven successful. Furthermore, the intense labor shortages of the early years had been reduced. And Lois Carr suggested that economic diversification led to home manufacture of woolen cloth on some plantations by the end of the century.

Sheep listed in St. Mary’s County Household Inventories

Sheep listed in St. Mary’s County Household Inventories

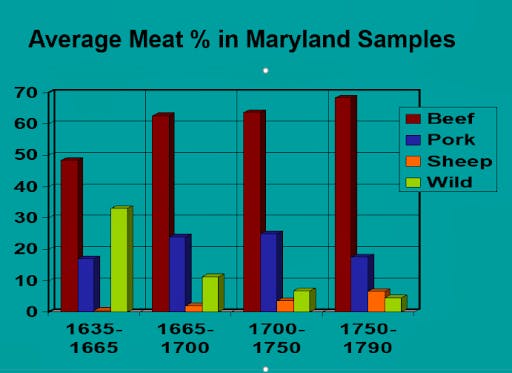

But the examination of bones from many different Maryland sites shows that sheep never became a major element of the diet. Beef and pork were the mainstays, supplemented by fish and oysters and poultry. This can be seen on the chart below. Sheep provide very little meat on 17th-centeury sites, while wild meat from deer and fish were far more important. Even during the years around the Revolutionary War, sheep make up only about 6% of the total meat on sites.

Comparison of the Meat Composition of the Maryland Diet over time from the analysis of Animal Remains.

Comparison of the Meat Composition of the Maryland Diet over time from the analysis of Animal Remains.

The reliance upon beef and pork was established early in the Chesapeake. As European settlement expanded westward over the Appalachians and toward the Mississippi River, people encountered similar forest covered landscapes with little pasture but an abundance of wolves and bobcats, and labor remained in short supply. Cattle and Swine were more adaptable to such environments. In long settled areas, sheep began being raised in small numbers, as much for their wool as meat, since clothing consisted primarily of linen and wool during the colonial era, and cloth was considerably more costly than today. But even there, lamb and mutton were only minor elements of the diet, as the Maryland data above shows.

Beginnings are important for they influence later developments. Foodways are shaped by tradition, circumstances, and the introduction of new items. Culinary patterns set early on in America were a mix of British tradition and new American foods acquired from Native peoples and they have endured. Central to the new foodway was beef and pork as core components of the meat diet. Despite their importance in Britain and Ireland, sheep never became a core element of the American diet. So we can to a considerable measure answer the question poised at the beginning of this piece. We do not find lamb burgers at McDonalds or Burger King because dietary practices established in the seventeenth century continue to influence us today.

About the Author

Dr. Miller is a Historical Archaeologist who received a B. A. degree in Anthropology from the University of Arkansas. He subsequently received an M.A. and Ph.D. in Anthropology from Michigan State University with a specialization in historic sites archaeology. Dr. Miller began his time with HSMC in 1972 when he was hired as an archaeological excavator. Miller has spent much of his career exploring 17th-century sites and the conversion of those into public exhibits, both in galleries and as full reconstructions. In January 2020, Dr. Miller was awarded the J.C. Harrington Medal in Historical Archaeology in recognition of a lifetime of contributions to the field.