In the 1970s excavations at the Van Swerigen site, many impressive artifacts were found. Most were the objects used in Van Sweringen’s elegant “Lodging House” or those from later occupants of the house in the eighteenth century. In the image below, you see excavators uncovering part of the kitchen brick floor at the site.

Digging at the Van Sweringen site where the type was unearthed.

Digging at the Van Sweringen site where the type was unearthed.

But there were some totally unexpected artifacts found. Among these are thin pieces of cast lead most with letters or symbols on one end. Below is a picture of some of the type found at the site. This was surprising because there was no evidence in the historical record that Garrett Van Sweringen was a printer. So what was printing type doing there and when did it date? Evaluating that was one of the early jobs assigned to me by Garry Wheeler Stone in late 1977. That was appropriate because I had grown up working in my father’s printing company, learning the craft in both its traditional and modern ways.

Some of the type recovered from the Van Sweringen Site

Some of the type recovered from the Van Sweringen Site

Unfortunately, all the type had been found in the plowzone, so it was mixed soils and I could not date them by using associated artifacts. Given that the Van Sweringen site was inhabited between 1664 and c. 1750, that was the only real time clue to start with. Investigating how type was made proved of no help because the basic form and method of casting had changed little over four centuries. Indeed, it was the same basic shape as the early 20th-century type I had set and printed with on the letter press at my dad’s in the late 1960s. But it was clearly hand-cast type and not machine-made, signifying that it was probably not of late 19th or 20th-century date. The specimens were mostly small case letters or punctuation marks and there was one displaying a floral decoration. A few were blank and would have been used as spacers. Corrosion had obscured some of the small letters. Only one piece offered much hope for any identification, a capital “M” as seen below.

Closeup of the Capital M

Closeup of the Capital M

It was a clear letter and the type face had one unusual feature. At the bottom of each side, there is a small vertical line coming off the letter. This is called a serif. But on the top of the M, a serif only appears on the right side in the above picture with none on the other side. This seemed unusual and it appeared in only one other 17th-century printed documents I was able to examine. Hence, it appeared that this was an uncommon type face for the period and the printer who used possessed a font with at least one distinct feature.

Given the date of the site, a 17th or early 18th-century date seemed most likely. Garry Stone knew that a William Nuthead had printed at St. Mary’s. Seeking more information, I call our historian Lois Green Carr who confirmed it saying “Yes, he was William Nuthead” and he came to Maryland around 1685 and died in 1695. The next question was do any of the documents he printed still survive? Lois said she believed there were some and would make an inquiry to the State Archivist Edward Papenfuse. Papenfuse confirmed that there were some believed to be Nuthead’s work, and he invited me to come up to the archives with the type so a comparison could be made.

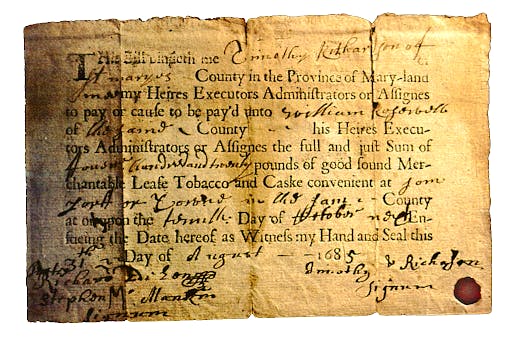

The first document Papenfuse pulled out was a Tobacco note. That is a colonial “IOU” to pay someone in tobacco and this one is dated 31 August 1685. It is attributed to the press of William Nuthead.

A Tobacco Note dated 1685 believed to be printed by William Nuthead (Maryland State Archives)

A Tobacco Note dated 1685 believed to be printed by William Nuthead (Maryland State Archives)

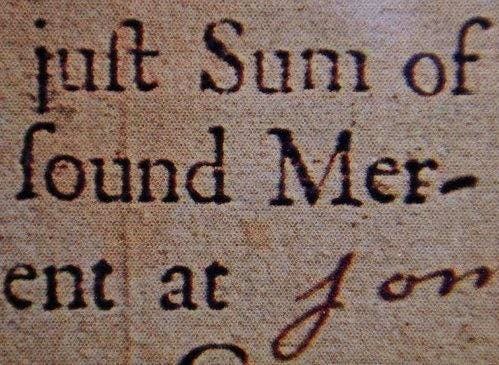

The capital “M” were the target letters and the image below shows a letter identical to the archaeological specimen. In it, the word “Mer-chantable” begins with a capital letter that has one upper serif missing. The printed letter is the reverse of the actual type face due to the printing process but I have reversed it here for a better comparison. Also on the “V” section of the letter, the line forming it on the serif side is fatter while the line on the opposite side is thinner. The style matches and the size is identical. This confirmed that the printer of the document used the same type face as the Van Sweringen letter and increased the possibility of it being from the press of William Nuthead. Other legal forms dating to this period at the Archives and also believed to be from Nuthead’s press show a similar letter. So a solid link between the archaeological find and the documents was made.

Closeup of the Tobacco Note and the piece of Type. Note that the type image has been reversed to allow a more direct comparison with the printed letter.

Closeup of the Tobacco Note and the piece of Type. Note that the type image has been reversed to allow a more direct comparison with the printed letter.

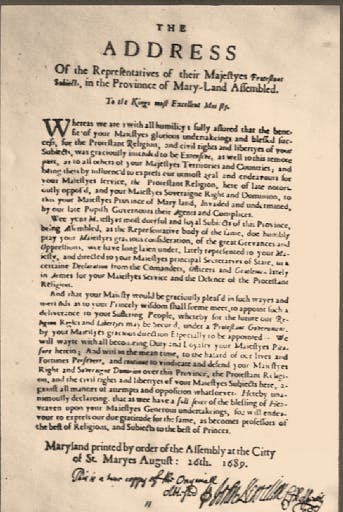

But can we link it directly to Nuthead? Comparing the letter to something that is an undisputable product of William Nuthead is necessary. Fortunately, there is one such document. His most significant publication is The Address of the Protestant Associators after the rebellion of 1689 that overthrew Baltimore’s government. The victorious rebels had Nuthead print a formal statement to be sent to the King and Queen and distributed both in Maryland and England. The single surviving copy is in the British National Archives. The overall document is shown first, followed by a closeup of the bottom part.

The Address of the Protestant Rebels to the King 1689 (British National Archives)

The Address of the Protestant Rebels to the King 1689 (British National Archives)

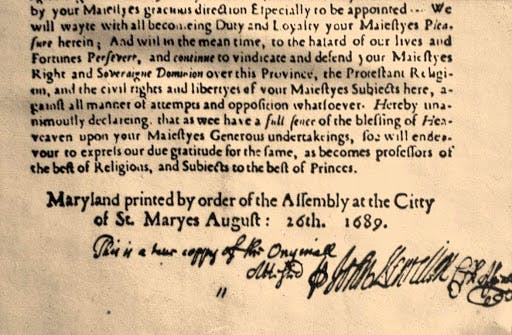

The lower section of the Address showing it was printed at St. Mary’s City in 1689 when William Nuthead was the only printer in Maryland.

The lower section of the Address showing it was printed at St. Mary’s City in 1689 when William Nuthead was the only printer in Maryland.

There is no question that this was printed by William Nuthead and if one examines” the M” in Maryland or St. Maryes at the bottom, you will see that the style is identical to the archaeological specimen. This is of the utmost significance because it proves that William Nuthead used a font with this letter style. And thus, the other documents in the Maryland State Archives with this font can likewise be securely linked to him.

This discovery came in early 1978 and the museum was planning its first major public program that year, an outdoor street theater style production entitled St. Maries Citty 1680. HSMC director of Interpretation Burt Kummerow decided that William Nuthead had a notable St. Mary’s City story and should be included in the program. That required a 17th-century printing press. Consulting with Smithsonian printing history expert Stanley Nelson provided valuable information and led to reconstruction plans based upon the c.1720 Benjamin Franklin press. Nelson said that there was virtually no difference between a 1680s and a 1720s printing press, so a wooden press of that type was built. I was given the task of obtaining certain press parts and tools (the ink balls), printing type, paper, etc. This all came together very rapidly in 1978 and being the only staff member with a printing background, it fell to me to become William Nuthead, as the picture below with the rebuilt press shows. Today that same press is the core of the Print House exhibit for the museum.

The rebuilt Nuthead Press and William Nuthead’s first impersonator, 1979.

The rebuilt Nuthead Press and William Nuthead’s first impersonator, 1979.

So who was the man with such an unusual name and a profession that was exceptionally rare in 17th century America? The evidence assembled by former HSMC interpreter Rod Cofield (2006), indicates that William Nuthead was probably born in London in 1654 of a William Nuthead, printer and wife Susana. The Maryland Nuthead apprenticed as a printer in London, as was the standard practice during the period.

Nuthead first reached America as an employee of Virginia merchant John Buckner. Arrival in 1682 is most likely because a February 1683 document addresses the Nuthead press. The Virginia Council had inquired about printing the Acts of the Legislature and Buckner replies that he had ordered Nuthead to not print anything aside from two pages produced for the Council to examine. In February of 1683, Buckner and Nuthead were ordered to post a bond of £100 to stop all printing until a decision from the King could be obtained. This is because control of the press was a serious concern to the Crown. Charles II blamed the press for its role in the rebellion against his Father in the Civil War. As a Royal colony, the Crown had control over printing. Deep distrust of the press had a long history in England, beginning with Henry the 8th. The opinion about the press was expressed by Virginia’s governor Sir Williams Berkeley in 1671 when he wrote

“I thank God, we have not free schools nor printing; and I hope we shall not have these hundred years. For learning has brought disobedience, and heresy and sects into the world; and printing has divulged them and libels against the government. God keep us from both!”

Berkeley was highly educated but had an elitist attitude and agreed that the press had been a factor in undermining the monarchy in England. The Lords of Trade in England consulted with the King and on 14 December 1683 issued a letter about the matter of printing in Virginia. They wrote that “no person may be permitted to use any press for printing upon any occasion whatsoever.” The new Royal Governor Lord Effingham arrived in early February of 1684 to enforce this instruction. In effect, this meant that printing was not allowed in any Royal colony and Nuthead was thus forbidden to practice his craft.

But Maryland was a proprietary colony and the Royal edict did not apply there. There is strong evidence that Nuthead obtained permission to move to the colony and follow his trade. Cofield found evidence that Nuthead was printing in Maryland before March 31, 1684, showing he did not stay long in Virginia after the prohibition. Someone in Maryland must have negotiated with Buckner to bring Nuthead to Maryland, and then receive permission from Charles Calvert to allow a press, but it is unclear who that was. Nuthead produced legal forms for the government and worked until his death in 1695. He is buried somewhere in St. Mary’s City. Nuthead had a “Print House” in the 1690s but its location has not yet been identified by archaeologists. However, an earlier print shop was located in the Town Center, in the area where the enslaved quarters of the Brome Plantation once stood. Archaeologists found dozens of pieces of printing type there, some in pits dating to the 1680s or early 690s. We have rebuilt that structure to interpret the Nuthead Press. Garrett Van Sweringen built that structure and this is a curious link. The original type was found at the Van Sweringen Council Chamber site. It seems that Nuthead printed for some undetermined length of time at both locations. Could the entrepreneurial and innovative Van Sweringen have been the patron bringing Nuthead to Maryland? No documents confirm that but type found at two Van Sweringen properties is certainly suggestive.

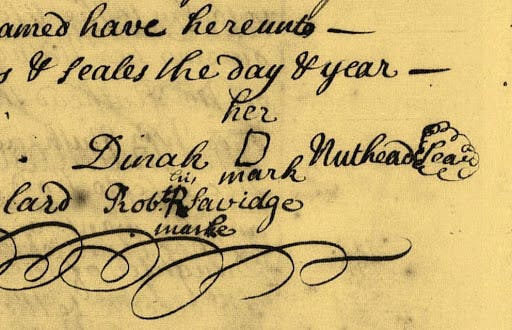

After Nuthead’s death and the move of the government to Annapolis in 1695, Nuthead’s widow Dinah joined other St. Mary’s City residents and relocated to the new capital. In 1696, she applied for a license from the government to print. This was granted and Dinah Nuthead became the first licensed woman printer in America. She only worked for a few years but there are a number of legal forms in the Maryland State Archives attributed to her.

Signature of Dinah Nuthead showing her mark, a Capital D

Signature of Dinah Nuthead showing her mark, a Capital D

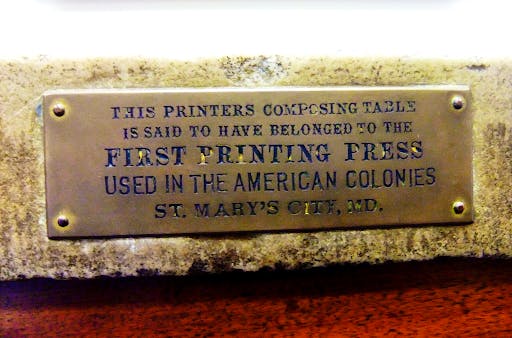

A few pieces of printing type and some documents are all that remains of the first printer in the United States outside of Massachusetts. But there is one more relic that is attributed to Maryland’s first printer. It was given to St. Mary’s Female Seminary and claimed to be his composing stone. Setting and leveling type and securing it in the metal frame requires a solid flat surface and this large stone would have served that purpose. It is seen here, now housed in the St. Mary’s Room of St. Mary’s College Library.

The Nuthead Composing Stone, St. Mary’s College of Maryland

The Nuthead Composing Stone, St. Mary’s College of Maryland

And on its edge is attached a brass plaque that read as follows:

It is a precisely shaped and carefully polished stone, and its size and thickness matches that of the print stone in the reconstructed Nuthead Press, which is based upon surviving examples. This correspondence seems too much for coincidence and this writer suggests that it may well have been part of the printing establishment run by William Nuthead.

Maryland has the distinction of having the first printing press outside of Massachusetts in English America. And in the person of Dinah Nuthead, the first female printer in the colonies. This was a skilled craft and rare even in England, where printing was restricted to London and the University Presses in Cambridge and Oxford. Printing was also quite controversial as William Berkeley declared and freedom of the press was not widely accepted. And yet Lord Baltimore allowed Nuthead to come and practice this craft in Maryland. His presence in the colonial capital was a step in the enhancement of urbanity that was very rare in most of the colonies. Although having a peculiar name, the Nutheads are significant to Maryland and America as pioneers of a skilled craft that would play a critical role in the spread of knowledge and the shaping of public opinion in the centuries that followed. And it is the curious style of a letter “M” that allowed them to be identified in the archaeological record of St. Mary’s City.

For Further information see:

Cofield, Rod

2006 Much Ado About Nuthead: A Revised History of Printing in Seventeenth-Century Maryland. Maryland Historical Magazine 101(1): 9-26.

About the Author

Dr. Miller is a Historical Archaeologist who received a B. A. degree in Anthropology from the University of Arkansas. He subsequently received an M.A. and Ph.D. in Anthropology from Michigan State University with a specialization in historic sites archaeology. Dr. Miller began his time with HSMC in 1972 when he was hired as an archaeological excavator. Miller has spent much of his career exploring 17th-century sites and the conversion of those into public exhibits, both in galleries and as full reconstructions. In January 2020, Dr. Miller was awarded the J.C. Harrington Medal in Historical Archaeology in recognition of a lifetime of contributions to the field.