In 1694, Maryland officials faced a dilemma. Maryland’s first Royal Governor, Sir Lionel Copley, had died and, along with his deceased wife, were resting in unburied lead coffins. It was assumed that directions would come from England to have their remains shipped home for burial. Both coffins were in the house the Copley’s had occupied, Philip Calvert’s mansion of St. Peter’s. As the winter turned to spring and then summer, no word arrived from England, and obnoxious smells were coming from the coffins. Something had to be done and the solution became an enduring element of St. Mary’s City history.

Copley’s presence in Maryland was due to the successful rebellion against Lord Baltimore in 1689. The rebels requested King William to take control of the colony and appoint a royal governor for Maryland. Sir Lionel Copley was selected. He was a military man who played a role in the Glorious Revolution of 1689 by supporting William and Mary. Copley and his wife, Anne Boteler Copley, and their three children arrived in Maryland in March of 1692. They soon occupied the vacant brick mansion of Philip Calvert and the structure became known as the “Governor’s House”. Copley began an ambitious effort to produce wealth for himself and run the colony. Among his legislative accomplishments was establishing the Church of England as the official state church in Maryland.

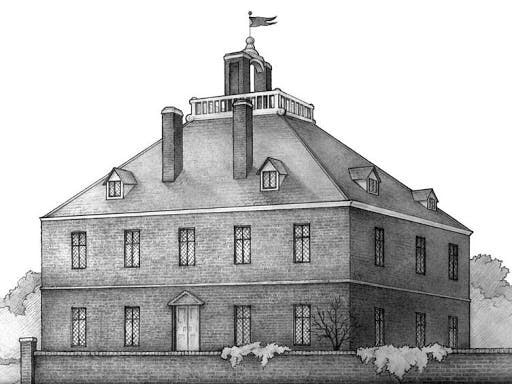

Conjectural Drawing of “the Governor’s House” or the “Great House” in which the Copley’s Lived and Died in Maryland. It was built by Philip Calvert c. 1677 and called St. Peters.

Conjectural Drawing of “the Governor’s House” or the “Great House” in which the Copley’s Lived and Died in Maryland. It was built by Philip Calvert c. 1677 and called St. Peters.

The Copleys had a troubled life in Maryland. Records suggest that they were sick much of the time and Copley designated representatives to travel for him and perform various duties because of his illness. It is likely that this was in large part “the seasoning” that nearly all Maryland immigrants, whether enslaved, servant or royal governor, suffered. Anne died one year after coming to the colony on March 5, 1693. Six months later, on 9 September, Sir Lionel also died after what was described as a long illness. It is curious to note that he apparently had not buried his wife but had her placed in a lead coffin and kept her at St. Peters; perhaps he intended to ship her remains to England for burial. The evidence that she was not buried comes from an order issued by the Council of Maryland in July of 1694 that finally addressed the fate of the Copley’s. This order stated that

“It being Represented to his Excellancy [Governor Sir Francis Nicholson] that the Bodies of the late Governour Copley and his Lady deceased lye still Uninterred at the Great house and considering it was expected some Order should have been received er’e this time for Conveying the same by some Mann of Warr or other Vessell for England, but there appearing as yet no such Order, and fearing longer delay of interring the same may prove obnoxious to the parts hereabouts; therefore Ordered that immediate care be taken for preparing a Vault to lay the said Bodies in …” (Archives of Md. 20:120-121).

But where? Although the Brick Chapel was the major cemetery for the city, that would be highly inappropriate for the staunchly anti-Catholic Copley. Given his status as the representative of the Crown, the more suitable place was determined to be near the 1676 State House, Maryland’s seat of government. It is likely that Governor Nicholson himself made this decision. A Richard Benton was hired and paid 4850 lbs. of tobacco for building this vault and John Lange given another 1110 lbs. for bricks and labor. Construction began in late summer in a spot 36 feet from the northeast corner of the State House. It is highly likely this was the first burial in an area that would later become Trinity Cemetery. The vault was completed by late September.

The “Solemnity” of interment occurred on 5 October 1694. Unfortunately, no record of the ceremony survives. We can surmise that the burial of this representative of the King was as impressive as the colonial government could make it. The original order stated

“… that the Ceremony of interring the same be performed as the next Provinciall Court with all the decency and Grandure the constitution and circumstances of Affairs will admit off; And that three brass Guns, being all that’s to be had be in readiness and the Militia of the adjacent parts.”.

A document reveals that this was followed because the militia leaders were issued an order in late September of 1694 to assemble on 5 October and “to be present with their Troope and Companys and that all things be gott in readiness Against that time pursuant to former Order” (Archives of Md 20: 146). It is thus reasonable to conclude that on that October day at Church Point, the Copley’s were interred with salutes from cannon and volleys from the muskets of the Maryland militia. A few weeks later, the decision was made to move the government to Annapolis and any intention of placing a grave marker for the Copley’s was forgotten in the bustle of relocating and building a new capital. It would be 228 years before the Copley’s resting place finally received a formal marker, installed by the Colonial Dames in 1922, as seen below.

The Copley Grave Marker in Trinity Church Cemetery at St. Mary’s City

The Copley Grave Marker in Trinity Church Cemetery at St. Mary’s City

The Copley’s largely vanished from memory. By the late 1700s, legend had developed that their burial place was the Calvert Vault and held the remains of Leonard Calvert, Lady Jane Calvert and a young Cecil Calvert. Memory of a vault obviously remained in the local community. In a 1799 letter, this was specifically noted:

“The oldest people now living, have for many years past spoke of a vault that was at Saint Mary’s Church [today Trinity Church], in which was one of the first American governors and his lady, who were in leaden coffins and embalmed for the purpose of being sent and interred in England …it was determined a vault should be erected and they enclosed therein, and door locked and the key thrown into the river. This was the account which was handed us from the oldest people now living, who had been informed by their fathers, and they got it from their fathers, etc., but none of them remembered their names” (James Thomas Chronicles of Colonial Maryland 1900:379).

That same year, the vault received a new type of attention. A group of medical students

under Dr. Barton Tabbs and other individuals decided to investigate the vault. On 27 July 1799, after four hours of hard labor, they broke through the top of the brickwork, and entered the tomb. They found two wooden crates that contained lead coffins. They opened the larger one and concluded it contained the skeleton of an adult male, “In the coffin of the man was only the bones which were long and large. His head was sawed through the brain removed, and filled with embalmment, but he was not so well done as the other, or had been there much longer as he was much more gone” (Thomas 1900: 379).

The smaller coffin could not be opened and they took it out, moved it to a shed on the nearby Mackall plantation and were able to open the completely soldered shut coffin. One of the investigators, Alexander McWilliams, wrote a letter about it to his mother and it deserves to be quoted in full:

“We removed the lid and to our surprise saw within it another coffin of wood. The lid of this being knocked off, we saw the winding sheet perfect and sound as was every other piece of garment. When the face of the corpse was uncovered it was ghastly indeed, it was the woman. Her face was perfect, as was the rest of the body but was black as the blackest negro. Her eyes were sunk deep in her head, every other part retained its perfect shape. The loss of three or four of her upper teeth was supplied with a piece of wood between. Her hair was short, platted and trimmed on the top of her head. Her dress was a white muslin gown, with an apron which was loose in the body, and drawn at the bosom nearly as is now the fashion only not so low, with short sleeves and high gloves but much destroyed by time. Her stockings were cotton and coarse, much darned at the feet, the clocks of which were large and figured with half diamonds worked. Her gown was short before and gave us a view of her ankle. Her cap was with long ears and pinned under the chin. A piece of muslin two inches broad which extended across the top of her head as low as her breast, the end was squared and trimmed with half inch lace as was the cap. The body was opened and the entrails removed and filled with gums and spice, and the coffin filled with the same. She was a small woman, and appeared delicate.”

This was a remarkable case of preservation and other accounts state that within five hours of opening her coffin, only bones were left. This must have been a situation where the coffin, fully sealed by soldering the lead, along with the embalming actions stopped decay, a sort of suspended animation. When fresh oxygen and humidity intruded with the opening, this steady state changed dramatically and led to rapid decay. McWilliam’s description is very valuable for it is the earliest account of a 17th-century person being buried clothed in America. Most individuals were interred wrapped in a shroud, but not with clothing. Being buried clothed was a very new fashion in England. Furthermore, this is an exceptionally early case of embalming.

Her coffin was returned to the vault and the brickwork resealed. Some public outcry was heard about this although others found it of much interest and were sorry they had not participated. And the incident brought forth some notable historical information about the vault from local people. McWilliams added at the end of his letter that:

“Since writing the above I have heard a man say who is sixty years of age, that it was Copely. He got his information from his father who was eighty years of age when he died, and his was handed him by his great grand father who built the vault and came in as a servant to this Copely. This seems to be the best account, and most probable”.

This was in 1799 and is a significance example that historical memories about events in St. Mary’s City remained among the local residents over a century later.

There were additional openings of the Copley Vault including one by the minister of Trinity Church in 1922. The last opening was conducted in 1992 and provided fascinating insights about the vault, their lead coffins and the Copley’s. The purpose was to acquire data about lead coffins to guide the Project Lead Coffins effort at the Brick Chapel. We had no data about how they would have been constructed in the American colonies, nor their strength or weight. The vestry of Trinity Church generously gave the museum permission for a one day entry in April of 1992. We prepared by first excavating the soil over a part of the vault top and identified the hole created in 1799, which is the low area in the picture here. We were surprised to see that the vault top was not curved as expected with an arch but had been fully leveled off so that it was originally at or very near the 17th-century ground surface. I think this suggests that some type of monument or grave marker was originally planned for the Copley’s.

The top of the Copley vault, showing its original flat top and the 1799 entry hole (Left), and a view through the hole down to the lead coffin of Anne Copley (Right)

The top of the Copley vault, showing its original flat top and the 1799 entry hole (Left), and a view through the hole down to the lead coffin of Anne Copley (Right)

We used the same hole as the 1799 investigators so as to not further damage the vault. The talented mason Raymond Cannetti carefully cut into the brick patch, opening the hole for entry (he would later securely close up the hole with a more robust brick seal than we found). Inside we saw the two lead coffins resting side by side. Scattered on the floor were remnants of the wooden “carrying case” that had originally held the lead coffins. The exterior wood cases were almost certainly added because it was thought the coffins would be shipped to England.

The Lead Coffins of Sir Lionel Copley (left) and Lady Anne Copley (right), as found in 1992.

The Lead Coffins of Sir Lionel Copley (left) and Lady Anne Copley (right), as found in 1992.

Physicist and Lead Coffin Project technical director Mark Moore measured the coffins, studied their construction, and determined the thickness of the lead in varied places on each coffin, a key piece of data to estimate overall weight. The woman’s coffin was made from several sheets of lead cut to shape around a wooden inner coffin that were soldered together; this is what produced the airtight tight seal that accounted for the high degree of preservation described in 1799. The man’s coffin was less well made, with lead sheets soldered in some places and nailed in others.

Then, forensic scientists from the Smithsonian Institution and the National Museum of Health and Science, led by Douglas Owsley, examined the human remains to determine their sex, stature, age and any clues about their lives the bone could reveal. This proved that they were indeed a man and women. Sir Lionel Copley (b.1648–d.1693) was 45 at his death and his wife Lady Anne (b.1660–d.1692) was 32. This historical data was compared to the osteological evidence which showed that the male skeleton was from 45 to 49 years of age and the woman was from 30 to 34 years old, thus helping confirm the Copley identification. Furthermore, the woman’s skeleton had birthing scars, and the Copley’s are known to have had three children. Sir Lionel stood 5 foot 9 inches while Anne was 5 foot 4 inches tall. He had several healed fractures, had lost three teeth and one tooth was an active abscess at the time of death. Anne had lost eight teeth and three more had serious decay. Owsley concluded that she had a diet that was high in sugar consumption, something her high status would have allowed. The scientist also confirmed that both skeletons showed cut marks that indicate they were embalmed. With the possible exception of Philip Calvert, this is the earliest evidence for embalming in English America.

Scientists examining the remains of the Copley’s.

Scientists examining the remains of the Copley’s.

A final clue to confirming that the skeletons were the Copley’s came from the composition of their bones. Tiny samples were taken from each and the Carbon 13 ratio in the bones showed that they had diets high in European cereal grains. When corn is an important part of the diet, or the meat of animals that have fed on corn plants is consumed, a different Carbon 13 isotope ratio is found. This supports the history that the Copley’s were newly arrived from England and not residents of Maryland for very long. Significantly, this data from the Copleys and that from the Calverts in their Lead Coffins led to the development of a valuable new forensic tool by which Carbon 13 can distinguish skeletons of English born people from Chesapeake born individuals, whether American Indians or Colonists.

The vault itself measures 10 by 10 feet and has an arched ceiling. The brick is well laid and the original entryway into the vault is seen in the picture below. It was fully brick up and over this entrance was a wooden lintel of which only portions now survive; most of its former shape is indicated by the hollow space. The mason laid the brick in what is called English bond using oyster shell-derived lime mortar.

Interior view of the Copley Vault showing the brick up entryway

Interior view of the Copley Vault showing the brick up entryway

Perhaps the most enigmatic observation made during the brief Copley vault investigation are two letters that were scratched into Anne Copley’s coffin; these were also noted by the 1799 investigators. I photographed them and they are seen below. The carefully inscribed letters “A L” were found on the lid of Anne’s coffin.

Picture of the letters “A” and “L” that appear on the top of the woman’s coffin.

Picture of the letters “A” and “L” that appear on the top of the woman’s coffin.

We do not know what these two letters stand for. However, being something of a romantic, this writer has a theory. I suggest that these stand for Anne and Lionel and were inscribed by a grief-stricken man onto the coffin of his newly lost and beloved wife. If so, they are a mark of enduring human love, affection and connection.

The Copley project provided very important evidence about Maryland’s first Royal Governor and his wife. It scientifically confirmed that they are indeed the Copley’s, gave essential evidence for the development of a new isotopic tool for forensic analysis, and provided invaluable data about lead coffin construction that guided Project Lead Coffins. Sir Copley is one of only two 17th-century English Royal Governors buried in the United States; the other is Richard Coote, 1st Earl of Bellemont, buried at St. Paul’s Chapel in New York City. The 1799 opening is also the earliest investigation of colonial burials recorded in the United States. Although often overlooked by visitors today, the burial vault of Sir Lionel and Lady Anne Copley is significant to Maryland history and a unique part of the St. Mary’s City story.

About the Author

Dr. Miller is a Historical Archaeologist who received a B. A. degree in Anthropology from the University of Arkansas. He subsequently received an M.A. and Ph.D. in Anthropology from Michigan State University with a specialization in historic sites archaeology. Dr. Miller began his time with HSMC in 1972 when he was hired as an archaeological excavator. Miller has spent much of his career exploring 17th-century sites and the conversion of those into public exhibits, both in galleries and as full reconstructions. In January 2020, Dr. Miller was awarded the J.C. Harrington Medal in Historical Archaeology in recognition of a lifetime of contributions to the field.