Deep in the lore about early Maryland is the most famous tree in St. Mary’s City. The “Old Mulberry” stood on Church Point were it was long a very prominent sight. Why this tree is notable is because it witnessed the entire 17th-century history of St. Mary’s, from Yacocomico village and early English settlement to the City of St. Mary’s, its flourishing, decline and disappearance. Legend tells that Leonard Calvert met under it to acquire the site from the Yacocomico people, the charter and Lord Baltimore’s directions were read to the newly arrived settlers near it and even the first Catholic mass at St. Mary’s City was said under it. But is any of this true?

The earliest reference in literature to the tree is found in the 1838 novel Rob of the Bowl by John Pendleton Kennedy. While a novel, Kennedy claimed it was as much history as invention and he clearly had done considerable research including a visit to St. Mary’s City. His introduction provides a description of the few remnants of the city in 1836. This includes the brick foundations of the 1676 State House. Over its ruins stood

“a storm-shaken and magnificent mulberry, aboriginal, and contemporary with the settlement of the Province, yet rears its shattered and topless trunk…an august and brave old mourner to the departed companions of its prime.”

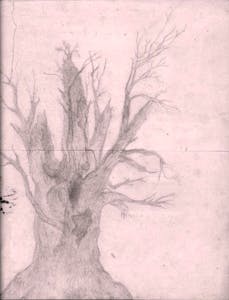

Kennedy cut a piece off the tree during his visit and made into a cane that he presented to the Maryland Historical Society in 1857. The earliest depiction of the mulberry tree was drawn by Seminary student Miss Piper in 1852. This original drawing is now owned by HSMC, a gift of Mrs. J. Spence Howard Sr. in 1934, and shows the tree mostly dead although a few branches of life might have still been present. From the picture we can tell that it had lost its crown by that time but had a very large trunk measuring perhaps six or eight feet in diameter. The mulberry tree had clearly been an impressive and long lived specimen of its species and stood in a most prominent location.

The Mulberry as it appeared in 1852

The Mulberry as it appeared in 1852

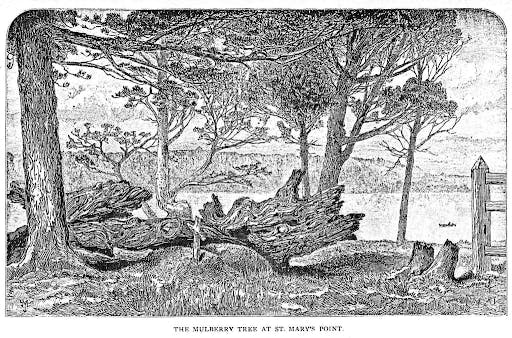

Within a few decades, a storm knocked over the surviving part of the tree. This is indicated by the next illustration of the mulberry in 1876. It appears in the volume Popular History of the United States by William Cullen Bryant and Sidney Gay. At that time, the fallen mulberry looked like this.

Remnants of the Mulberry Tree as it appeared in 1876 (from Bryant and Gay)

Remnants of the Mulberry Tree as it appeared in 1876 (from Bryant and Gay)

They described it as being on the point and “its decayed and blackened trunk, lying where it fell but a few years ago [before 1876] yet marks the place of its growth. They then added as very significant statement:

“Under this tree, according to well authenticated tradition, Leonard Calvert made a treaty with the Indians of the village.”

This is the earliest printed statement about this I have found to date. Bryant spent time with Dr. John Brome who owned most of St. Mary’s City and had grown up there. Brome deeply respected the history of St. Mary’s and Bryant and Gay wrote that he “has carefully preserved many local traditions.” It thus seems possible that Brome may have been the source of this account, repeating a legend passed on by earlier generations.

In 1890, in a belated recognition of the 250th anniversary of Maryland, the state erected an obelisk where the ancient mulberry had stood and dedicated it to Leonard Calvert, as seen below.

The Leonard Calvert Monument where the old Mulberry once stood (1890)

The Leonard Calvert Monument where the old Mulberry once stood (1890)

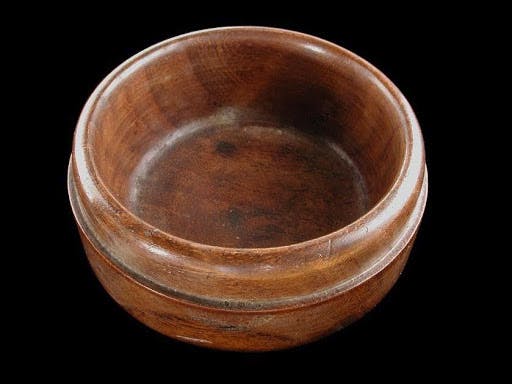

The wood from the old tree was collected and turned into varied crosses, cups, gavels, canes and other mementoes. HSMC owns one of these objects as viewed here.

Small bowl made from the wood of the Mulberry Tree

Small bowl made from the wood of the Mulberry Tree

But a large portion of the wood was used in Trinity Church. It appears as crosses on the end of pews, was used to construct the entire altar rail as seen below and in other elements. The altar rail displays a silver plaque which says “Presented by St. Mary’s Seminary in Memory of Dr. John M. Brome”, and was likely installed soon after his death in 1887.

Mulberry Tree wood used for Crosses on the Trinity church pews

Mulberry Tree wood used for Crosses on the Trinity church pews

The Altar Rail in Trinity Church, St. Mary’s City, made from the Mulberry Tree

The Altar Rail in Trinity Church, St. Mary’s City, made from the Mulberry Tree

Legends about the Mulberry Tree appear again in the important volume Chronicles of Colonial Maryland published by James Walter Thomas in 1900. Thomas did extensive research for the book and had interviewed numerous elderly people over the years to obtain information including Dr, Brome. Thomas wrote about “the historic “Old Mulberry” tree, under whose broad, spreading branches the first colonists of Maryland assembled and under which, also, traditionary history says, the first mass at Saint Mary’s was celebrated , and the treaty between Governor Calvert and the Yaocomico Indians was made.

He further stated that “on it were nailed the proclamations of Calvert and his successors, the notices of punishments and fines … and all notices for the public attention” and related that in prior years, “curious relic hunters were able to pick from its decaying trunk, the rude nails which held the forgotten State papers of two centuries and more ago. Posting of such notices would most likely have occurred between 1676 when the state house was opened and 1708 when the county government was moved to Leonardtown.

The only period reference to the Mulberry Tree comes from a 1681 document in the Archives of Maryland. It is a deposition given by Garrett Van Sweringen in which he said “That on Saturday last in the afternoon he came by the Mulberry Tree where he Discoursed with one of the Burgesses about Repairing the house for the Committee to sit in.” This was in August of 1681 and seemingly the shade of the tree was used by people in the vicinity of the state house. Can any of this be substantiated in the early 21st Century?

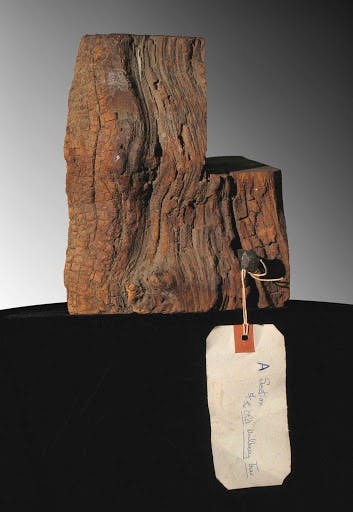

One artifact of note is a large piece allegedly from the original Mulberry Tree in possession of the museum. It is seen below and the identifying label reads “A Section of the Old Mulberry Tree.” Very significantly, the string is tied to a handmade wrought nail that was driven into the wood, thus supporting the Thomas statement that’s items were attached to the tree with nails.

Specimen in the Museum Collection identified as being from the original Mulberry Tree

Specimen in the Museum Collection identified as being from the original Mulberry Tree

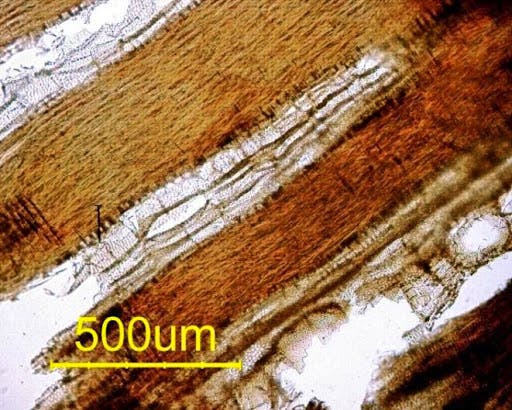

But is it really the wood from a mulberry tree? To answer that, curator Silas Hurry submitted a small sample of its wood to one of the nation’s premier wood experts – Dr. Harry Alden. Alden did a thin section of the wood that is seen below. By examining its physical structure, he was able to determine that it is indeed from a mulberry tree.

A Thin Section of the museum artifact that proves it is the wood of a Mulberry Tree

A Thin Section of the museum artifact that proves it is the wood of a Mulberry Tree

This supports at least one part of the Mulberry Tree story but was it really the case that “Under this tree, according to well authenticated tradition, Leonard Calvert made a treaty with the Indians of the village” that Bryant and Gay reported? Some evidence of relevance is that over the past 30 years, I was able to examine the disturbed soil in this area from the digging of new graves and the installation of ground lights and other excavations. There is much prehistoric oyster shell and stone artifacts on the back or North side of the church and these extend toward the Leonard Calvert monument. And very significantly, a few specimens of Yeocomico pottery were found, a pottery type used in the decades immediately prior to 1634 by the Yacocomico people. This does not prove the home of the Werowance stood there but it is strong evidence that native peoples lived on Church Point in the late 16th and early 17th centuries.

Legends and myths develop everywhere there are humans because they have important roles in society. Some are based upon actual events and others are pure fantasy. Is it possible that something happened under or near the mulberry tree in the first days of settlement? We can never say for sure. Perhaps the Mulberry Tree is the same as Plymouth Rock. The rock is allegedly where the Pilgrims stepped ashore in 1620. But the earliest recorded statement about this is 1741 from a very elderly man born in 1647. While the rock was almost certainly present in that year, it is only legend that connects it with the footsteps of the pilgrims. This idea became embellished with time and the stone took on a significance no other rocks in the United States is given. Many pieces were chipped off as souvenirs and it is estimated that only about one third of the original rock survives, as seen here. The 1620 date was carved on it in the 1880s. There was a significant effort to recognize and commemorate the past in the 19th-century, as a sense of nationhood strengthened. A shrine was built over Plymouth Rock in the 1860s and the erection of the Calvert monument in 1890 was a part of that same cultural movement. It was during this same period that the first accounts of the Mulberry Tree were recorded. As a curious aside, I remember an encounter with a group of visitors who sailed to St. Mary’s City around 1980. At the time, the Statehouse was the only exhibit and served as the visitor center. The people approached the staffer and asked “Could you tell us where the Rock is”. They clearly confused St. Mary’s with Plymouth.

Plymouth Rock as it appears today

Plymouth Rock as it appears today

There is something about legends at St Mary’s City. After the capital moved in 1695, the population became stable and families lived in the area for generation after generation. Memory survived. One good example is the burial vault of Royal Governor Sir Lionel Copley and Lady Anne Copley next to the 1676 State House. They were buried in lead coffins there in 1694 but by 1799, one story told that the vault contained the remains of Leonard Calvert, Lady Jane Calvert, and a young Cecil Calvert. After the coffins were opened, inquiries were made and one person came forward who saide that the tomb contained the remains of a Copley, for his grandfather had helped lay the brick for the vault. After a century, the actual facts were still remembered by some in the area. Similarly, John Pendleton Kennedy in 1836 was taken to the sites of the State House and the brick jail, told of the presence of associated stocks, a pillory and ducking stool (later confirmed by HSMC in the surviving documents), and the brick Jesuit Chapel. He also described the impressive brick home of the “Baltimore family” which we know was Philip Calvert’s mansion of St. Peter’s.

In the later 19th and early 20th centuries, other information was collected. James Thomas spoke with locals for his Chronicles of Colonial Maryland and sites such as the State House, Chapel, St. Peter’s and the St. John’s sites were all pointed out to him. Dr. Brome had built his house on top of what was believed to be Smith’s Townhouse and very near the Leonard Calvert House. Historical analysis suggests they were not in that location but our 1980s excavations proved that the Brome House was on top of the Calvert House that had also been William Smith’s townhouse during a later phase of that building’ long history. Historical tradition had been correct in a number of cases, although not all. Another example is that during 1934 celebration, the brick remains of a structure not far from the Brome house were uncovered as the first archaeological display of a colonial site in Maryland. This was known from enduring memory as the Council Chamber site, later the Van Sweringen Lodging House. Thus, there were some notable elements of information about St. Mary’s City that survived in the memories of local people from colonial times up to the 20th century. This is almost certainly attributable to the remarkable stability of the population, with many families tracing their ancestry back to the 17th century in the area.

It is fashionable to discount or refute legends and myths of the past. This can be a valuable contribution. But at the same time, folklorists have found that many legends have a basis in actual events, no matter that they later became modified or embellished with repeated retelling. Whether Leonard Calvert met the Yaocomico leader near the Mulberry Tree can never be proven to have happened, although archaeology does imply that there was Yaocomico habitation in that area. Perhaps the story of the first mass and charter being read to the first settlers there are embellishments to the legend. On the other hand, given the lore about the vanished city that did survive, it is equally impossible to say something did not happen there. Despite this uncertainty, it is undeniably the case that the ancient Mulberry Tree was the last living witness to the founding of the colony and in the words of James Walter Thomas “had watched over the City in its infancy; it its development and prosperity, and its pride and glory, as the metropolis of Maryland”, and it therefore merits a place in the fascinating story of St. Mary’s City.

About the Author

Dr. Miller is a Historical Archaeologist who received a B. A. degree in Anthropology from the University of Arkansas. He subsequently received an M.A. and Ph.D. in Anthropology from Michigan State University with a specialization in historic sites archaeology. Dr. Miller began his time with HSMC in 1972 when he was hired as an archaeological excavator. Miller has spent much of his career exploring 17th-century sites and the conversion of those into public exhibits, both in galleries and as full reconstructions. In January 2020, Dr. Miller was awarded the J.C. Harrington Medal in Historical Archaeology in recognition of a lifetime of contributions to the field.