When seventeenth-century archaeology began in Maryland in the early 1970s, it was believed that a number of original buildings from that time period still stood in the state. Most were at least partially of brick and the owners were proud to dwell in such ancient buildings. But research has a tendency to change our understanding of things and such was the case with early Maryland architecture. A combination of archaeology and tree ring dating of the timbers from which many of the buildings were constructed revealed that nearly all were of 18th-century date or even later. Only three structures were built before 1700 and the oldest is the Third Haven Quaker Meeting House in Easton, Maryland, build in 1684-85. So what happen to the rest?

One answer came from the 1970s work at the St. John’s site. While the main house erected in 1638 displayed a stone foundation, the remains of other buildings there were much less obvious. A structure thought to be a kitchen was identified because it had a brick chimney foundation. Then in 1973, excavators in uncovered the first evidence for a completely different type of building unknown to architectural historians. The first clue was a large intrusion or feature with a dark circle of soil in it. This is the photo of that feature which turned out to be a very large posthole for a building. It consists of a large hole dug in a rectangular shape, a wooden post was then placed in the hole and the hole refilled with the backdirt. Because of the way it was first excavated, the fill soil is mixed up unlike the much more uniform and undisturbed natural earth around it, providing an essential clue for the archaeologists. The dark circle is the more organic soil from where the wooden post either rotted away or was pulled out and darker topsoil washed into the vacant space. We call these the post hole and the post mold.

Picture of the first building posthole identified at St. John’s

Picture of the first building posthole identified at St. John’s

Garry Stone then directed the excavators to do a cross section of the posthole by digging out one half of it. As you can see below, this revealed the dark mold of the former post extending to the bottom of the hole. It was buried nearly three feet deep. The post size, about one foot across, and the depth indicated this was not a fence post but part of a building.

Cross-Section of the posthole showing the dark post mold within the backfilled soil

Cross-Section of the posthole showing the dark post mold within the backfilled soil

Stone directed additional excavations to find related post and this was successful, allowing him to determine that this was a building that measured 20 feet wide and 30 feet long. We then backfilled the area and moved on to other projects. The importance of the find is that it showed early Maryland settlers had constructed buildings that rested not on masonry foundations but wooden posts. Work soon after at the Van Sweringen site found additional evidence for this type of architecture that was named earthfast or post-in-the-ground. No one had anticipated the prevalence of such buildings, but the growing body of archaeological evidence suggested this had been a common if not the primary method of building homes and other structures in the 17th-century. At the same time, colleagues in Virginia were finding remains of the same type of buildings, showing that this was a regionwide method of construction. One good Virginia example is the 1640s plantation of Thomas Pettus, a member the Virginia Council.

Excavation of the Pettus Site along the James River, showing the lines of postholes that supported this elite earthfast home., c.1640-1680.

Excavation of the Pettus Site along the James River, showing the lines of postholes that supported this elite earthfast home., c.1640-1680.

This evidence was summarized in a pivotal 1981 article entitled Impermanent Architecture in the Southern American Colonies by Cary Carson, Norman Barka, William Kelso, Garry Stone and Dell Upton. Cleary early colonial architecture was very different from what had been assumed before sustained archaeology in the region. These scholars concluded that the settlers had revived a Medieval type of construction that had declined as England was deforested. In the remarkably timber rich setting of the early Chesapeake, this was a highly efficient means of building homes, tobacco barns, and other structures. A related factor is that the tidewater Chesapeake region has very little stone aside from river cobbles. Bricks could be made but skilled artisans were rare, making bricks expensive. And they were difficult to transport any distance. Earthfast architecture made good sense with the ready availably of massive trees and timber of superb quality. As we sometimes say, their firewood was as good and probably better than the finest veneer wood you can buy today. From the forest could be shaped the posts, wall, and roof timbers, as well as the siding and roofing of thin riven oak clapboards. Skilled labor was is short supply in the Chesapeake and wages were two to three times greater than in England. Garry Stone’s research has found that a skilled carpenter or housewright with two or three assistants could put up a small house in three to four weeks and a tobacco barn in about two weeks. Earthfast architecture was fast, efficient, and used freely available timber. Its major drawback was impermanence. Britain had no termites but they were a part of the Chesapeake environment and no chemicals were available to defend against them. Only masonry foundations or entirely brick buildings were able to deter the termite and allow those buildings to survive much longer. With care and repair, an earthfast building could last for a number of decades but rarely for a century or more.

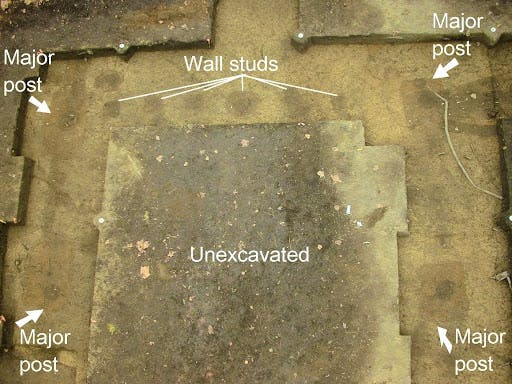

A fine case study is the first earthfast house discovered at St. Mary’s City. Some 30 years after Stone’s crew found it, HSMC archaeologists returned to conduct further excavations at St. John’s in preparation for an exhibit building at the site. Led by this author and Ruth Mitchell, we were finally able to uncover this entire structure in the front yard of St. John’s. At the north end of the building, the big post holes were obvious, with an orange-tinted backfill around the post mold. They were set at 10 foot intervals, which became standard in Chesapeake architecture. But the real surprise that had not been seen previously is what was between the big structural posts. Every 2.5 feet, there was a small post mold. Instead of the walls resting on a wooden sill, the wall studs were set into the ground in very small holes. This created a very solid building, although it greatly increased the avenues for termites to enter. You can see the posts and wall studs defined in the picture below. Note that we intentionally left the center of the building unexcavated for future generations.

The north half of the earthfast structure uncovered at St. John’s showing the numerous posts

The north half of the earthfast structure uncovered at St. John’s showing the numerous posts

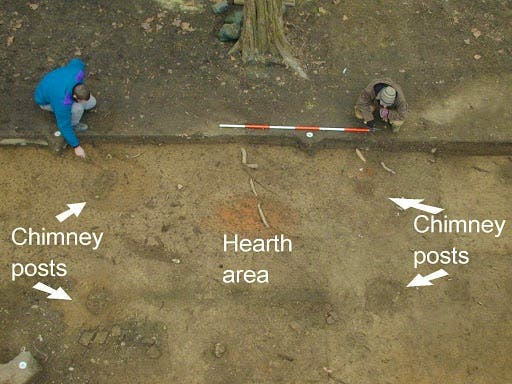

At the south end of the building, we found another surprise. Set into the end wall was evidence of a fireplace. The hearth was indicated by bright orange fire altered soil and the four posts that supported the wattle and daub chimney were well defined. Significantly, the archaeological evidence for the wall studs along that wall were visible, indicating that this chimney was a later addition to the building. It had originally been unheated.

The South end of the building showing the evidence for a wattle and daub chimney addition

The South end of the building showing the evidence for a wattle and daub chimney addition

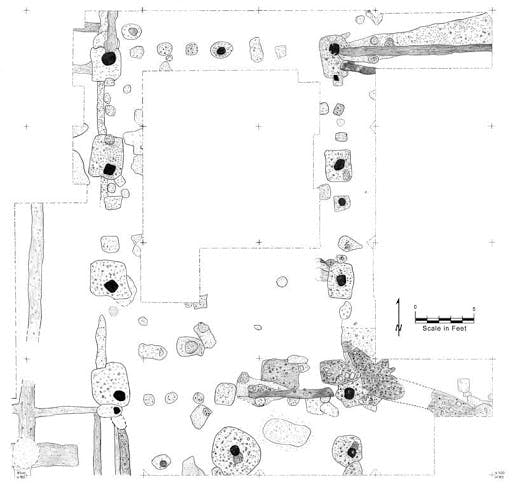

All of this evidence was consolidated into an overall plan for the building seen below. A precisely measured plan is essential for us to figure out the nature of the building that once stood there. It was a 20 foot wide and 30 foot long building. The walls were divided into 10 foot segments or bays. At the center of the north and west ends or gables, a smaller central post provided support for these 20 foot long spans. The regular 2.5 foot spacing of the studs for the building’s walls can be clearly seen. I have outlined the walls in red. At the top right and bottom left there are several generations of fences extending off the corners of this building. Their presence is solid evidence that this structure lasted for a considerable time, at least several decades.

Archaeological Plan View of the Earthfast Building called the Quarter

Archaeological Plan View of the Earthfast Building called the Quarter

Study of where the large wooden posts were placed within the postholes tells us that this building was constructed by raising four pairs of posts, each pair connected by a tie beam or celling joist timber. This is the first building in Maryland identified as being erected in what architectural historians call “bents” or the post pairs. We replicated that method when building the 1660s Godiah Spray Tobacco Plantation Exhibit in the early 1980s. Here is the crew erecting the “bents” for the 40 foot long tobacco barn back in 1983.

Raising the Bents of a 17th-century Tobacco Barn at the Godiah Spray Plantation

Raising the Bents of a 17th-century Tobacco Barn at the Godiah Spray Plantation

Using all the archaeological data abut this building and other architectural research, we worked with the talented artist Leslie Barker to create a conjectural image of what this long vanished building could have looked like, and the result is seen here.

Conjectural Image of the Quarter as it might have appeared c 1680. Art by Leslie Barker.

Conjectural Image of the Quarter as it might have appeared c 1680. Art by Leslie Barker.

So what was the purpose of this building? The artifacts suggest it was built in the 1650s and stood into the 1690s. The fact that it was originally unheated is significant. A dwelling or servant’s quarter would have been heated. Furthermore, the solid construction and use of ground set studs indicates it was meant to be a strong building. Such evidence points to it being built by Dutch merchant Simon Overzee for his commercial enterprises. In 1658, Overzee engaged in a partnership with New Amsterdam (New York) merchant Augustine Hermann for a three-year venture selling Maryland tobacco to the Dutch. Overzee had even entertained Hermann at St. John’s when he came to St. Mary’s for negotiations between the Maryland and New Netherland governments. It seems likely that this building was constructed as a secure storehouse for Overzee’s goods. His sudden death in 1660 ended the venture. Soon afterward, the new governor Charles Calvert, arrived in Maryland and moved into St. John’s. With a large household and numerous visitors, he may have converted the storehouse into a lodging we call the Quarter. That use continued into the late 1600s.

This building is significant because it helped transform our understanding of colonial architecture in the Chesapeake. Uncovering traces of it gave Maryland archaeologists the first clue that the early settlers may have lived in buildings more ephemeral than historians once thought. The adoption of this ancient method of construction was an important element in the process by which the colonists adjusted to the new setting of Maryland, making efficient use of the most available materials and time in a setting where skilled labor was in short supply and expensive. This building also told archaeologist that they had to sharpen even more their skills at reading the dirt to identify these long vanished buildings and develop new methods of excavation to fully understand them. As has been shown many times before, the clues are there if we can just be smart and diligent enough to recognize and collect them, and then decipher the evidence to unravel more mysteries of the past.

About the Author

Dr. Miller is a Historical Archaeologist who received a B. A. degree in Anthropology from the University of Arkansas. He subsequently received an M.A. and Ph.D. in Anthropology from Michigan State University with a specialization in historic sites archaeology. Dr. Miller began his time with HSMC in 1972 when he was hired as an archaeological excavator. Miller has spent much of his career exploring 17th-century sites and the conversion of those into public exhibits, both in galleries and as full reconstructions. In January 2020, Dr. Miller was awarded the J.C. Harrington Medal in Historical Archaeology in recognition of a lifetime of contributions to the field.