We often say that all traces of Maryland’s first capital have vanished below ground. That is true with one significant exception. It is the remnant of an earthen mill dam built only four years after the colony was founded. Located in Mill Creek at St. Mary’s City, it was constructed by Thomas Cornwallis in 1638. We know this because of a letter Cornwallis wrote to Lord Baltimore on 16 April 1638 that survives in The Calvert Papers. It reads:

The building of the mill was I Assure your Lordship a vast Charge untoe mee, for besides the Labor of all my owne servants for two yeeres, I was at the Charge of diverse Hirelings at 100 weight of tobacco the month with dyet…is all uttery lost by the Ignorance of a foolish millwright whoe set it upon a Streame that will not fill soe much in six weeks as will grinde six bushels of Corne,, soe that myself nor the Colony is any whit the better for all the paynes and costs…I intend…in removing it toe a better Streame, if I can but see such a number in the Colony as will mayntayne a mill with greeste”.

It is certain that Cornwallis did move it to a new location on the stream that became known as Mill Creek in subsequent centuries. It is documented in a 1641 land survey that states “where the mill now standeth”. When Mark Cordea patented his one acre lot to build Cordea’s Hope in 1674, it was described as “beginning at a stake in the road which goes from the old Mill Damm to the old Countrey house”, which is also called the Leonard Calvert house. This and other references suggest that the mill was not operating in the last decades of the 17th century but the mill dam had become integrated into the city street system by serving as a causeway over the creek.

I first encountered this ancient survivor in 1973 when serving as a digger at the St. John’s site. This is what it looked like in the summer of that year. The top of the dam was kept clear of vegetation at the time because Spence Howard’s cattle used it as a dry path to cross the creek, the same as 17th-century colonists did coming to or departing the city.

The 1638 Mill Dam as seen in 1973

The 1638 Mill Dam as seen in 1973

Silas Hurry has written a valuable document tracing the history of mills in early St. Mary’s and he found that the mill on Mill Creek was not working in 1723 either. In that year, a document describes “St. John’s Creek” (now Mill Creek) as “It being the place where formerly was said to stand a water mill”, and specifically notes the remains of an old mill dam. However, there is evidence that a mill was again operating at St. Mary’s City in the late 1700s for the then owner John Mackall had a “mill house” on his plantation. There are no subsequent references to the mill.

Today, the dam is much as I originally observed it nearly 50 years ago, with a bit more vegetation. This picture shows the dam and the mill pond area beyond it in 2019. It now stands about 5 feet above the stream bed, although there has clearly been considerable erosion. The mill pond to the right has filled up with sediment, and varied plants are growing in it as seen in the next picture. In the 1990’s pollen expert Dr. Gerald Kelso took a core sample from the mill pond and found that the likely bottom of the mill pond was 4.5 feet below the current surface in the old pond. Given erosion of the mill dam, this suggests that the original pond was 6 to 7 feet deep. The lower section of the core contianed dark silt and sand, suggesting organic soil erosion and the bottom layers of the pond. Much of the upper fill is attributed to intensive plow agriculture in the late 1700s and 1800s and the 1880s construction of an earth railroad trestle upstream from the dam that caused extensive soil disturbance and erosion. That seems to have caused much of the final filling up of the old pond.

The Mill Dam today showing trees growing out of it

The Mill Dam today showing trees growing out of it

The Mill Dam in the bottom left and filled up mill pond in the upper right.

The Mill Dam in the bottom left and filled up mill pond in the upper right.

One important feature of the existing dam is that it does not run in a straight line across the creek bed but curves on the east side. The dam runs straight across the valley of Mill Creek from the west side but about 30 feet before it reaches the opposite band, there is a pronounced turning or zig-zag in the construction as seen here. The straight part is extending from the left side here with the turn seen to the right. It formed a small notch in the dam layout.

Mill Dam showing the sudden curve in the earthwork on the east side

Mill Dam showing the sudden curve in the earthwork on the east side

This creates a low area as seen below. Why does the old dam have such an unusual feature? To answer that, we must investigate what type of mill Thomas Cornwallis might have built.

Low Area at the Curve on the Mill Dam’s East End.

Low Area at the Curve on the Mill Dam’s East End.

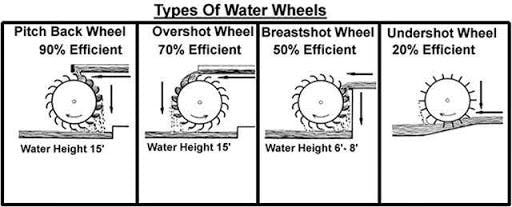

Constructing water mills depends in large part to the nature of the water source that will power it. There are three basic types of water wheels, the undershot, the breastshot and the overshot as this image illustrates.

The three main types of water powered mills

The three main types of water powered mills

The most efficient is the overshot wheel where the water can come from above the wheel, thereby using gravity and the water’s weight and flow to turn it. This demands a water source well above the wheel. Next is the breastshot wheel where the water comes at or just above the middle of the wheel but not above it. This requires that the water source be at least 6 to 8 feet high. It also takes advantage of gravity to create more power. The final example can work in many settings but is the least efficient. Water simply flows along the bottom of the wheel and powers it mostly by the strength of water flow. This can be used where higher water levels cannot be created due to topography or limited resources. So which one does the surviving evidence suggest for the 1638 mill? The undershot would be the first option as it is easy to construct and operate. There is no doubt that an undershot mill would have operated in the settling of Mill Creek and is the most likely.

However, the fact that the mill dam has that odd jog at the east end would seem of significance, since such a feature would probably not be needed for an undershot wheel. Could that area have held the mill house over a wheel pit so the wheel was low enough to receive the water from the mill pond at or just above its centerline, thus being a breastshot mill? A six or seven foot deep pond would allow such a mill if the wheel was low enough, and the area within the “notch” along the mill dam could have been dug out for the pit to allow this. Such a mill would have been considerably more efficient. We must keep this possibility in mind, but the answer can only come from archaeological testing at the site. In any case, a grist mill did once stand on Mill Creek perhaps somewhat similar to this 17th-century English example.

Seventeenth-Century English Mill of the Undershot type

Seventeenth-Century English Mill of the Undershot type

Given the evidence, the mill dam would have created a substantial mill pond. In the 1996 painting of St. Mary’s City by Walter Crowe, we tried to suggest this as seen here. Without doubt, current Mattapany road would have been underwater when the pond was extant, and that is the reason the dam itself became the preferred means to cross the creek into the city. However, I must report that it is unsure if the millhouse is on the correct side of the dam in this painting.

Conjectural Painting of the Mill dam and pond ca. 1680. By Walter Crowe.

Conjectural Painting of the Mill dam and pond ca. 1680. By Walter Crowe.

Where was the first mill Cornwallis built between 1636 and 1638 which failed to work because of its poor placement? So far, no specific place has been located. But there is one spot elsewhere on Mill Creek that is quite curious. It is another earthwork located near where Mill Creek enters St. John’s Pond below the college library. The college walkway over Mill Creek built in 1969 runs just below it. It is now heavily overgrown but in 1973 when I first saw it, the earthwork was very obvious as this picture shows. It is clearly cut in the middle with surviving sections found on both ends, and it once spanned Mill Creek. In 1995, I inspected this with Dr. Patrick Martin, one of the nation’s foremost mill experts and he immediately concluded that was indeed a mill with a wheel pit obvious on the west side and traces of a possible water raceway still apparent.

Lower Dam on Mill Creek near the College Library, perhaps the failed 1636 effort.

Lower Dam on Mill Creek near the College Library, perhaps the failed 1636 effort.

Could this have been the location of Cornwallis’s first mill? If so, perhaps its failure was not stream flow so much as its placement in a low-lying area insufficient to trap a necessary body of water to provide a strong water flow. In April of 1638, Cornwallis had not yet decided on the upper Mill Creek site, so it is unclear which stream he was referring to in the letter to Lord Baltimore. I raise this as a possibility because both dams are on the same creek but in different topographic situations. Again, archaeological testing will be required to assess it. There is a possibility that this is where Mackall had his 1790s mill, although the location again would not be as good for mill operation as the upper stream site. Pollen testing just above this dam in 1983 found that this location has been a marsh for several thousand years. Perhaps the steeper sides of the ravine further up Mill Creek facilitated better pond formation.

There is much to still learn about these mill sites at St Mary’s City. Their purpose was to grind grain instead of saw timber. Silas Hurry did assemble evidence that Charles Calvert had a mill built at the place we now call Great Mills in the 1660s or 1670s and it may have had sawing as well as grain grinding capability. In any case, Thomas Cornwallis’s massive investment in a grist mill for “Our Town We Call St. Maries” failed. In large part, people living far apart on disperse plantations made distance a factor and they had the ability to pound their own corn into cornmeal. Given high death rates in early Maryland, it is also possible that the millwright died. There are documents showing that in the 1650s, Governor William Stone brought a windmill to St. Mary’s City from New England and erected it on Church Point. If the Cornwallis mill were still operable, it would not have been needed.

The 1638 mill dam at St. Mary’s dates to the first years of Maryland and is the only element of the vanished city that is still visible above ground. We must leave open for now the question of whether the lower mill dam is even earlier and created in 1636. In any case, this mill is the first effort at industrial development by Marylanders. And it is hoped that some day this venerable remnant of the ancient capital can be made available to the public, and perhaps even rebuilt.

About the Author

Dr. Miller is a Historical Archaeologist who received a B. A. degree in Anthropology from the University of Arkansas. He subsequently received an M.A. and Ph.D. in Anthropology from Michigan State University with a specialization in historic sites archaeology. Dr. Miller began his time with HSMC in 1972 when he was hired as an archaeological excavator. Miller has spent much of his career exploring 17th-century sites and the conversion of those into public exhibits, both in galleries and as full reconstructions. In January 2020, Dr. Miller was awarded the J.C. Harrington Medal in Historical Archaeology in recognition of a lifetime of contributions to the field.