Discovering a Coffee House

Identifying the purpose of long vanished buildings is one of the challenges confronting archaeologists. The form and construction of a building is important along with the associated artifacts. For historical archaeologists, clues often come from documents. One fascinating example of this is found in the 1698 will of one of St. Mary’s City’s most prominent residents, Garrett van Swearingen. In it, he bequeaths to his son Joseph “ye Council Rooms and Coffee House and land thereto belonging”. We know the Council Chamber was the elegant lodging house he operated for members of Maryland’s colonial elite, as is indicated by many documents in the archives. But the coffee house reference is unique. Clearly, van Swearingen did not use the term accidentally and its linkage with the Council Rooms strongly suggests that the Coffee House stood in the vicinity. But some questioned whether such a fashionable urban institution could have really existed in 17th-century Maryland. If it did, where was it and how could we identify it as a coffee house? Given the total lack of other historical references, only archaeology could answer these questions.

A knowledge of coffee was carried to Europe by travelers to Arabia and Turkey. Originally, it was thought to have medicinal properties, as championed by the scientist Sir Francis Bacon. By the 1650s, however, it moved from being a medicine to a popular stimulating beverage, thus launching the coffee house. These became fashionable in mid-17th-century Europe and grew in popularity in England in the second half of that century. The Dutch also developed a love of coffee and coffee houses appeared in Amsterdam and Rotterdam around this same time. But 17th-century coffee is not something you will find at Starbucks. A Turkish proverb of the era proclaimed it should be “black as hell, strong as death, sweet as love”, and coffee grounds were often included. It was more like a very dense expresso than the coffee we drink. One mid-17th-century sampler described it as a “syrup of soot and the essence of old shoes”. But the stimulating effect was undeniable, addictive, and drove its popularity.

The oldest still operating coffee house in England was established on the High Street in Oxford in 1654, as seen here. I made sure to patronize such a venerable establishment while working in Oxford.

The oldest operating Coffee House in England, established in 1654 at Oxford

The oldest operating Coffee House in England, established in 1654 at Oxford

Coffee was the primary beverage served in a coffee house, although later tea and chocolate were offered. Alcohol was also available in British coffee houses, as one memorable quote by Daniel Defoe in 1714 about the town of Shrewsbury indicates. He said it had “the most coffee-houses . . . I ever saw in any town, but when you come into them they are but alehouses, only they think the name of coffee-house gives a better air.” Food, on the other hand, was limited and not a significant offering of coffee houses. The coffee house was primarily a place for social interaction, where news could be shared and opinions expressed. Among the topic could be politics, current events, commerce, and gossip. Overtime, different coffee houses attracted specific clienteles. One example is of merchants, shippers and sailors frequenting Edmund Lloyd’s Coffee House in London, which led to the establishment of the renowned insurance firm, Lloyd’s of London. Coffee houses in Oxford originally charged a penny per cup, leading to their being dubbed “Penny Universities” because of the academic discussions and intellectual exchanges that could be found there. One characteristic of the 17th-century coffee house in Britain is that it was an egalitarian institution, open to all comers, regardless of class, wealth, or station in life. They also had rules of behavior that required civil debate and acting with a measure of politeness. A 1674 Rules and Orders of the Coffee House listed these and featured the earliest known image of an English coffee house. It is seen here. Note that coffee drinking and tobacco smoking were clearly linked in a coffee house.

A 1674 illustration of an English Coffee house

A 1674 illustration of an English Coffee house

In any case, it was a fashionable institution that slowly migrated across the Atlantic. The first coffee houses in America are not well documented. It appears that ones were established in New York and Boston in the latter decades of the 17th-century. In Virginia, the Charlton Coffee House was opened in Williamsburg in 1765, and it may be the oldest in that colony. This makes the Van Sweringen statement about a coffee house at St. Mary’s City in the late 17th-century of special interest.

Archaeology began at the Van Sweringen site in 1974, uncovering portions of the Council Chamber. To better evaluate the area, the entire field was plowed, and a surface collection made. This identified a brick concentration some distance from the Council Chamber structures. It was tested and the brick found to be from the chimney of a small building. Intensive excavations followed in 1977 and the structure was fully uncovered, and its features investigated. The picture here shows the building after the plowed soil had been removed and the features fully excavated.

Van Sweringen’s outbuilding after full excavation in 1977

Van Sweringen’s outbuilding after full excavation in 1977

Archaeologist found that the building had measured 18.6 by 21 feet with one wall occupied by a stout brick chimney. The structure was box framed and its sills rested on four wood blocks or pilings. The unusual chimney shape suggested to Garry Stone that the smaller right section was a bake oven and Van Sweringen had built this in 1677 for his planned brewing and baking business. That enterprise does not appear to have met with much success due to a series of incidents. Artifacts tell us that this structure had better refinements than a typical outbuilding. It had wooden floors, plastered walls, glass windows and decorative fireplace tile.

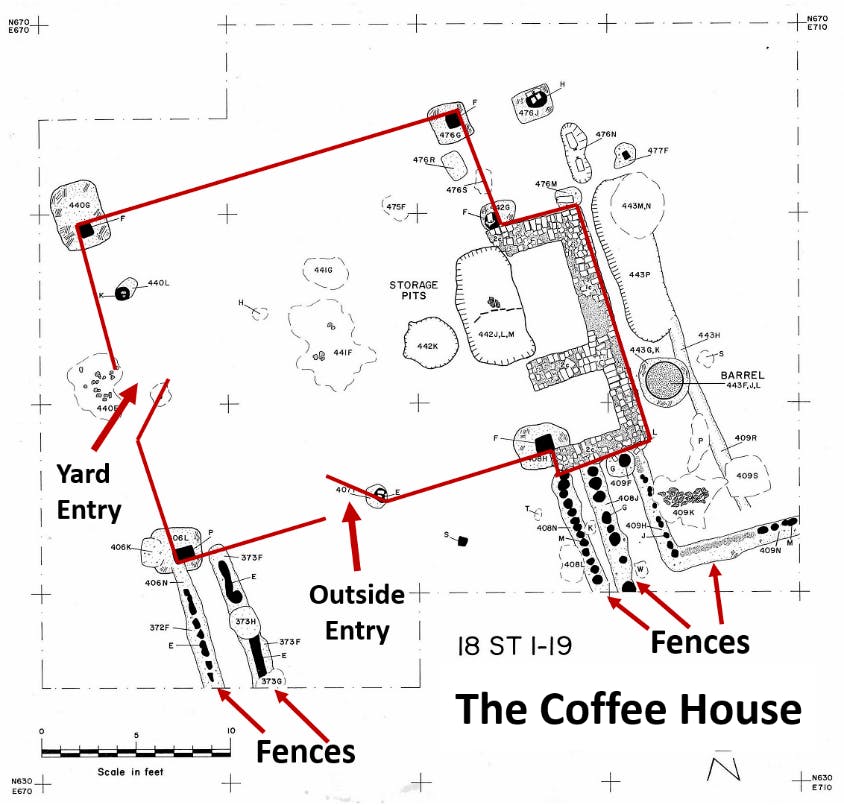

Below is the archaeological site plan of this building, showing all the features associated with it. North is to the top on this drawing. On it I have indicated the two doors of the structure, one going toward the Council Chamber on the west side and another on the south side.

Archaeological Plan of the Outbuilding believed to be Van Sweringen’s Coffee House

Archaeological Plan of the Outbuilding believed to be Van Sweringen’s Coffee House

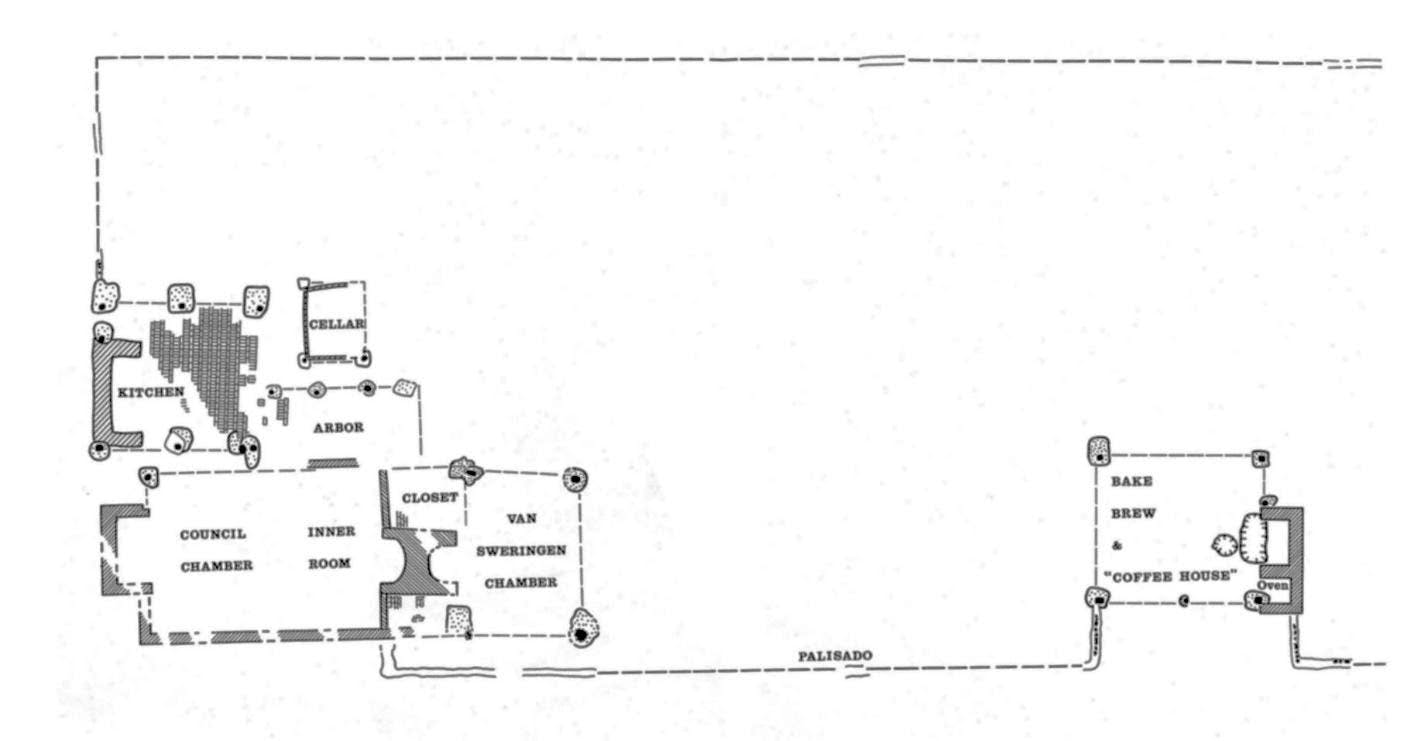

What is most peculiar are the palisade fence ditches found on the south side of the building. The van Sweringen site was enclosed by a palisade fence and the finding of several generations of fence ditch segments indicates that this general yard configuration endured for years. While these fences defined and limited access to the interior of the van Sweringen site, they extended outward from the southern corners of the outbuilding to create a public entry corridor to that structure. There is no other reason for this configuration except to allow people to come into the building without first going through the private spaces of the yard. The overall layout of the Van Sweringen property is shown here, indicating this outside entry. Such an arrangement would not be expected for a typical outbuilding.

Site plan of the overall Van Sweringen site showing the buildings and enclosing palisade fence.

Site plan of the overall Van Sweringen site showing the buildings and enclosing palisade fence.

To better understand what purpose the building had, we next turned to the domestic artifacts which consisted of pottery, tobacco pipes, bones, and glass. Their frequencies were compared with the same artifact types found around the large main building complex at the site, the Council Chamber and Kitchen. These can be seen on the site plan above. Ceramic drinking vessels including cups, mugs and small bowls made up 58% of the outbuilding vessels but account for only 39% of those from the Council Chamber/Kitchen. Dining vessels (plates, dishes) comprise only 8% of the outbuilding ceramics, while the Council Chamber complex had nearly 20%. Animal bones are 8% of the artifacts at the outbuilding but make up 28% of the materials from the Council Chamber and Kitchen. Most surprising are tobacco pipes. More pipes fragments were recovered from this small structure (962) than from the larger main house complex (884). In terms of percentages, pipes account for 40% of the outbuilding artifacts compared to only 18% from the Council Chamber/Kitchen area. It was clearly a location of intensive smoking, and some of these imported tobacco pipes are shown here.

Tobacco Pipes from the Van Sweringen Site

Tobacco Pipes from the Van Sweringen Site

The outbuilding yielded a very unusual artifact collection. It was clearly a place of much smoking and drinking but little food consumption. Most notable among the recovered items are sherds of very rare Turkish pottery. Called Kataiyai ware, a partial reconstruction shows that the vessels were small, elaborately decorated coffee cups, and are seen here. Most of these fragments were found in a midden halfway between the outbuilding and Council Chamber but the 2005 field school recovered several sherds at the outbuilding. Vessels of this type are very rare, having been found only a few other times in North America.

Turkish Kataiyai pottery recovered from the Van Sweringen site. The form is of small bowls that are traditionally associated with coffee consumption

Turkish Kataiyai pottery recovered from the Van Sweringen site. The form is of small bowls that are traditionally associated with coffee consumption

All the evidence indicates that this outbuilding was unusual. It was well finished, and the artifact assemblage indicates it was a place where drinking and smoking occurred with great frequency, but little food was consumed. This is unlike an inn or ordinary were food was a central element. And the fencing indicates it was intended to be accessible by the public. It is reasonable to conclude that this building was Van Sweringen’s Coffee House. It apparently functioned in the 1680s and 1690s and was the first coffee house in the Chesapeake region. This does not preclude some brewing or baking being conducted there, but the fences and artifacts suggest that a more public use was intended.

The presence of a Coffee House in the provincial capital of Maryland is an urban amenity that was not expected at this early date. On the other hand, Garrett van Sweringen was a sophisticated and innovative individual with ambition to succeed in the occupation of “Serving the Country”. His Council Chamber lodging house served the elite of the colony. If he followed its egalitarian tradition, his coffee house was a place where he could appeal to a broader swath of Maryland society, and the concentration of tobacco pipe implies it was a popular place. It is fascinating that the clue given by two words in a 17th-century will prompted an intensive archaeological exploration which eventually allowed us to conclude that Garrett Van Sweringen was indeed one of the first to introduce this fashionable urban institution to British America in the city he did so much to help develop.

About the Author

Dr. Miller is a Historical Archaeologist who received a B. A. degree in Anthropology from the University of Arkansas. He subsequently received an M.A. and Ph.D. in Anthropology from Michigan State University with a specialization in historic sites archaeology. Dr. Miller began his time with HSMC in 1972 when he was hired as an archaeological excavator. Miller has spent much of his career exploring 17th-century sites and the conversion of those into public exhibits, both in galleries and as full reconstructions. In January 2020, Dr. Miller was awarded the J.C. Harrington Medal in Historical Archaeology in recognition of a lifetime of contributions to the field.