We sometimes metaphorically speak of following in our ancestor’s footsteps, but can we find their actual footsteps? That is a question I have long pondered after a surprise find in 1978. In that year we were digging at the Garrett Van Sweringen site occupied between 1664-c.1745. Although the buildings were all of earthfast or post-in-the-ground construction, Van Sweringen had added a brick veneer to a part of the building, erected brick chimneys and in the kitchen, laid a brick floor. Archaeologists were retrieving many oyster shells, bricks and partial bricks from a rubble filled cellar that you can see here. The bricks were demolition rubble from the 17th-century buildings. The excavators measured them and then stacked them up for later movement to a storage area.

I visited the site regularly to see what was being found and what to expect in the lab. After discussing the days work, I started back to the car, walking past the stacked bricks. Something caught my eye. Sunlight racked across a broken brick that by chance was on the top of the pile, revealing some type of unusual impression. A thunderstorm had come through the night before, which washed off the surfaces of the top bricks, better revealing the impression. I picked it up and was astonished to see part of a human footprint on the brick, as seen here. It consisted of the toes of a left foot. The size suggests it was made by a bare foot 6 to 9 year old child. In the 17th century, after the brick had been molded and laid out to dry in the brickyard, a young boy or girl stepped on the brick, leaving an enduring record of their presence. The brick was locally made and they might have been the child of the brickmaker or perhaps a young orphan sent as an indentured servant to Maryland. There is no way of knowing. But it is a very significant find, being the only human footprint discovered in over half a century of archaeology at St. Mary’s City.

There were once 17th-century footprints all over St. Mary’s City, in the roads, on paths, and around the yards of houses, made by people during the course of everyday life. But rain, plowing, plant growth and grading has obliterated all of these. So is there any place we might seek evidence of human traffic and their footsteps?

One possibility that came to mind many years ago relates to water. Unlike sites at Jamestown where they dug wells, settlers at St. Mary’s City never dug any wells. Instead they relied upon the abundant freshwater springs. Father Andrew White wrote in his account of Maryland’s founding that the land “abounds with delicate springs which are our best drink’. For every home, bringing water from a spring would be a daily chore and this would have occurred many thousands of time over the course of a site’s habitation. Could such prolonged foot traffic have left any evidence?

One of the specializations in our profession is landscape archaeology. This includes identifying ancient field systems, former roads, earthworks, gardens and other features etched on the land. It is sometimes humorously referred to as seeking the “Lumps and Bumps” of the past. Studying the lay of the land or topography is a key part of this area of investigation. In our first excavations at the St. John’s site in the 1970s, Garry Stone made a precise topographic map of that 1638 plantation house location and the surrounding land. Our excavations uncovered the main house and several outbuildings including a kitchen. The water source for St. John’s, and an important factor in John Lewger’s decision to build his house there in the first place was a springhead. To any who have carried water from a well, the buckets are heavy when filled and the closer to the house, the better. Inspection of the landscape around St. John’s allowed Stone to identify an unnatural feature. It was an indented area in the side of the ravine going down to the spring. Once the building locations were determined, it was found that the indentation was the closest place to the side doors of St. John’s house and the kitchen. It was a path worn down by people making countless trips to get water from the spring over a span of 80 years of habitation. Although now overgrown, I tried to clear enough brush for you to see this feature in the landscape today.

Finding such traces requires developing your eye for them and recognizing landscape features that have no geological explanation. I used this skill in our efforts to find the 1640s plantation of Daniel and Mary Clocker. Dan Clocker arrived as an indentured servant to Thomas Cornwayles in 1636 and Mary came as a servant with Margaret Brent in 1638. They married in the 1640s and obtained a land tract in St. Mary’s City in 1650. Dan and Mary ran a successful tobacco plantation, supplemented by his skills in carpentry and hers in medicine and midwifery. Dan and Mary died in the mid-1670s and their family continued to live on the land, albeit in different houses and locations, until Clocker’s great, great, great grandson sold the land in 1877.

Preliminary archaeology determined the general area of the 17th-century plantation, not surprisingly, it was located near a spring. That spring continues to flow today, as is seen below.

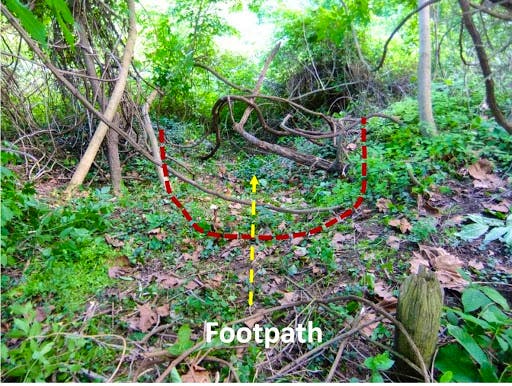

But there is an unnatural feature in this area, a long narrow depressed area in the ravine side. Inspection shows no erosional explanation for it such as a minor seep of ground water or from drainage. Here is a closer view.

This is the path created by the footsteps of Clocker family members going to collect water over many decades of time. Constant usage gradually wore down the soil, allowing a sunken path to develop. Dating from the 17t century, it has survived for over 300 years, despite trees growing up along its edges. As at St. John’s, the ravine side location insured that it was never plowed away.

There is one other colonial pathway that you have probably seen but did not recognize. It is adjacent to the same site the yielded the child’s footprint in the brick- Van Sweringen’s. It exists along the river bank, opposite the Council Chamber and its kitchen, as can be seen here.

A closeup of the actual ravine is below. It is now heavily overgrown but in the past was relatively free of vegetation and very obvious, traces of a narrow path could be seen that twisted down to the beach. Again, there was no springhead or a major drainage area that could have created it.

Instead, this is the route indentured servants and probably enslaved Africans took over a span of about 70 years to access a spring at the base of the cliff. It is steeper today than it would have been in the late 1600s or early 1700s because erosion has destroyed some of the shoreline. Archaeological survey of the beach area found a cluster of 17th century bricks around the bottom of this pathway which probably formed a small box near the springhead in which to collect the fresh water. This was a smaller spring than the major one located on the shore near the Leonard Calvert House, but it had the advantage of being close to Van Sweringen’s. In any case, carrying buckets of water up that slope must have required considerable exertion and is unlikely to have been a popular job. I know this because in my youth, it was sometimes my task to carry buckets of water from my grandmother’s well, and that was hard work even though the walk was all over level ground. Today, this spring is offshore due to erosion and sea level rise.

So while the footprints of Maryland’s early citizens have vanished, by reading the landscape, they have left us evidence of their walkways in a few out of the way places. These subtle features of the colonial landscape are yet another part of St. Mary’s City’s past that has survived, if only we can train our eyes to see them.

On final word about the child’s footprint. I am often asked “What was the favorite artifact you have found?” There are several but one of the top ones must be this brick. It’s discovery was due to pure serendipity. If an excavator had not been put it face up and on the top of the rubble pile, if there had not been a hard rain the night before to wash it, if I had not been in the precisely right location and if the sun had not been at just the right angle, this unique artifact would probably never have been discovered. As much as any artifact I have ever found, this brick allowed me to connect with a long forgotten child who ran across a brick yard some summer day over 300 year ago at a place called St. Mary’s City, leaving the only enduring trace of their presence on the Earth. It still prompts me to wonder who the child was, their experiences in Maryland, and what happened to them? We will never know who they were but it is this ability to directly connect with people of the past which is one of the most profound and appealing aspects of the field of archaeology, and what makes it such a fascinating endeavor.

About the Author

Dr. Miller is a Historical Archaeologist who received a B. A. degree in Anthropology from the University of Arkansas. He subsequently received an M.A. and Ph.D. in Anthropology from Michigan State University with a specialization in historic sites archaeology. Dr. Miller began his time with HSMC in 1972 when he was hired as an archaeological excavator. Miller has spent much of his career exploring 17th-century sites and the conversion of those into public exhibits, both in galleries and as full reconstructions. In January 2020, Dr. Miller was awarded the J.C. Harrington Medal in Historical Archaeology in recognition of a lifetime of contributions to the field.