Coming to early Maryland was a major risk for immigrants. One acquires immunities to the diseases in the region where you grow up. But such immunity typically does not transfer when migrating to new areas. Maryland offered a different climate and disease environment and there was a substantial shift in both diet and work patterns. The consequences of this were severe because people experienced a very high death rate and shortened life expectancy.

Getting reliable information about the topics of health and disease for people during the first century of European settlement in Maryland is not easy. Historical records are often silent or incomplete and fail to provide sufficient details about sickness and death. Furthermore, many diseases are not expressed on the human skeleton. Nevertheless, the efforts of historians and archaeologists have produced valuable insights on these topics.

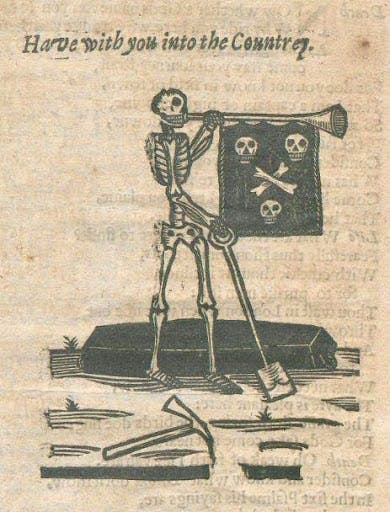

One of the most shocking findings is the shortness of life. A 20 year old male coming to Maryland could expect to live to about 45, if they were lucky. The data do not allow an accurate estimate of the experiences of women but there is some suggestion that they lived somewhat longer if they had survived their childbearing years. Pregnancy could be deadly. One case is the St. John’s site. In that single house, we believe three women died in childbirth between 1638 and 1662: Ann Lewger, Sarah Overzee, and Anne Calvert. Children in Maryland also had a high death rate, with estimates that up to 50% did not reaching the age of 20. Due to the high mortality rate, children who did survive were likely to have lost one or both parents while they were growing up and step-parents or guardians were common. This is in striking contrast to New England. The same 20 year old male going to Plymouth, Massachusetts in the mid-17th century could anticipate living to almost 70. The Chesapeake in general was an very unhealthy place for colonists. This 17th-century print rather well expresses this, suggesting you bring a shovel and coffin “into the Country.”

A 17th- century print about the need to prepare for burial. From https://pbs.twimg.com/media/CJT7S6GUcAEE1MY.jpg

A 17th- century print about the need to prepare for burial. From https://pbs.twimg.com/media/CJT7S6GUcAEE1MY.jpg

What were the causes of such sickness and death? Historical research suggests that the greatest single factor was malaria. It had been inadvertently introduced to the Chesapeake by Europeans and probably Africans. By itself not a major killer, it weakened the individual and made them more susceptible to other diseases. Malaria was found throughout the tidal Chesapeake, everyone was infected and suffered the characteristic symptoms of fever and chills, headache, fatigue, and swellings. A classic description of it in Maryland comes from Ebenezer Cook’s The Sot-Weed-Factor published in 1708. He writes:

“I felt a Feaver Intermitting;

A fiery Pulse beat in my Veins,

From Cold I felt resembling Pains:

This cursed seasoning I remember,

Lasted from March to cold December.”

All immigrants experienced what was called “the seasoning”, the adjustment to the new environment and diseases, especially malaria. Many did not survive seasoning and it is estimated that about a quarter of the new immigrants died within their first year. The colder climate of New England seems to have made malaria a less significant factor there, in part accounting for the pronounced differences in longevity.

Recently a fascinating letter was found in England that provides a most striking description of “seasoning” and the health challenges in early Maryland. This was discussed in Clues # 1. Written by Ann Truman from a plantation on the Patuxent River in April of 1671, she says

“… our deare Nanny dyed june 19th & one of our servants a litle before, the rest of us (through mercy) seasoned (as they call it) well, most of us in the sumer (3 months of wch was hot) had an ague & fevor wch held us about a week or fortnight, but have had our healths this winter. I was delivered of a son jan. 16th who lived but 10 dayes…”

This single plantation experienced two deaths from seasoning, another of a newborn child, and all suffered from “the seasoning.” And within a year of writing the letter, her husband James Truman was also dead. This is the only known written account from a woman about sickness and mortality to survive from early Maryland, it and powerfully expresses some of the hardships of migrating to Maryland.

But there were other causes of ill health in Maryland. These were described as “Agues”, “malignant Feavers”, “Swellings” and “Gripping of the Guts”. Precise diagnosis with such vague terms is difficult but it is believed that Dysentery was as serious as malaria. This disease, probably described as “gripping of the guts” or “the bloody flux”, is caused by either bacteria or amoeba and it is infectious. Abdominal pain and bloody stool are symptoms and dehydration is common. It is closely associated with poor sanitation and come from contaminated food or water or physical contact. It is possible that there were new Chesapeake species of the bacteria, but parasitic amoeba typically come from tropical areas. Given the nebulous descriptions, it is not possible to say which was endemic in early Maryland. Typhoid fever and even lead poisoning could have also caused intestinal pain. People weakened by malaria would also be more susceptible to communicable diseases such as influenza. Indeed, there are two periods of exceptionally high mortality in Maryland (1675-1677 and 1698-1699) vaguely described as “Infectious Times”; medical historians suggest that these were major flu outbreaks. Smallpox arrived in the Chesapeake in the later 1600s but it seems to have had limited impact. Unlike places like Boston that were densely populated with close human contact and which experienced repeated smallpox outbreaks, Maryland’s settlement pattern of dispersed plantations probably limited its spread. Besides disease, other documented causes of death are accidents such as in felling trees or being cut with an axe, warfare with the Susquehannock in the early decades, falls, drowning, murder, death in childbirth, and a few suicides. Given the richness of the natural environment and the effectiveness of food production, starvation or even malnutrition were not significant mortality factors in early Maryland, unlike the first years of Virginia.

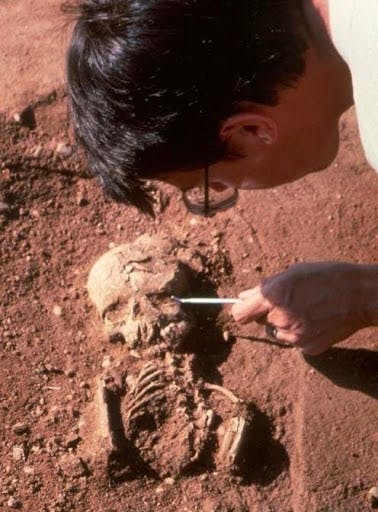

Archaeology adds new and important insights to this subject. None of the diseases discussed above leave any evidence on the human skeleton. However, Smithsonian forensic anthropologists led by Douglas Owsley have been assisting St. Mary’s City since the beginning of the Chapel project. This image shows Owsley making observations about one of the adult burials at the chapel. His amazing skill in reading a skeleton is providing valuable information about Maryland’s early colonists. He has identified broken bones, healed fractures, head trauma, abscesses, bone infections and evidence of both arthritis and osteoporosis on the people. Skeletal analysis also found that most individuals engaged in hard physical labor during their lives, as evidenced by highly developed muscle markings on the bones, something to be expected in a tobacco economy that was totally reliant upon human labor.

Dr. Douglas Owsley of the Smithsonian Institution examining and recording one of the Chapel site burials at St. Mary’s City, 1995.

Dr. Douglas Owsley of the Smithsonian Institution examining and recording one of the Chapel site burials at St. Mary’s City, 1995.

Not surprisingly given the historical evidence, the Chapel excavations found a number of small graves that were of children. This is important because there is so little documentary data about children in early Maryland. Seen here is a young child that had been buried so shallowly that the lower half of the skeleton had been destroyed by the plow.

Excavation of a small child buried at the Chapel site by Timothy Riordan.

Excavation of a small child buried at the Chapel site by Timothy Riordan.

Analysis of the remains of the 17th-century residents of Maryland continues. Indeed, Owsley and his co-worked Kari Bruwelheide are reexamining the Chapel burials. With two decades more experience, they are discovering many new insights about the people who once lived at St. Mary’s City. And for the first time, they are comparing the St. Mary’s City residents with those from Jamestown. This will be a unique and highly significant study of life and death in the early Chesapeake. When finished, all the remains will be returned to the Chapel site for interment in the burial vault built inside the chapel, with proper religious rites.

For this writer, one of the most affecting findings of all the askeletal research regards dentition. We take dentistry for granted but examining the teeth of the 17th-century settlers shows they had an almost total lack of dental care, aside from pulling a decayed tooth. Cavities on some individuals are massive and almost painful to look at. Perhaps the most egregious examples come from two of the highest status women in Maryland. One is Anne Wolseley Calvert, the first wife of Chancellor Philip Calvert. Anne was in her 60s at the time of death and she had lost 20 of her teeth and several of the remaining teeth were worn down to the roots. The other was Lady Anne Copley, the wife of Maryland’s first Royal Governor. Although only 32 years old, Anne had already lost 8 teeth and four of the remaining had active decay. Wealth did not give protection from such decay and may have even enhanced it by allowing greater access to sugar. But even indentured servants suffered from this problem. Perhaps the most disturbing example is of a 17 year old male found by Al Luckenbach in Anne Arundel County. Buried haphazardly in a cellar, there is a strong suggestion that he was murdered. This young man had huge cavities in many of his teeth. This is a picture of his jaw, showing the extent of the tooth problems. His upper jaw displayed an equal number of cavities. Being young, his permanent molars were still erupting. He must have been in constant pain. And the only pain killer available during the 17th-century was alcohol, to which he as an indentured servant probably had limited access.

Mandible of the 17 year old male found in an Anne Arundel County cellar, c. 1670. The extensive tooth decay can be readily seen. Photograph by Henry Miller. From the Written In Bone exhibit, Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution.

Mandible of the 17 year old male found in an Anne Arundel County cellar, c. 1670. The extensive tooth decay can be readily seen. Photograph by Henry Miller. From the Written In Bone exhibit, Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution.

Deciding to come to 17th-century Maryland involved a great risk. While religious freedom and economic opportunity were major incentives, as is still true for immigrants today, there was much danger. Sickness and death were a prominent part of life in the early colony. Only at the very end of the century did a native-born population begin to arise in Maryland. They developed natural immunities to some of the region’s diseases and experienced somewhat longer life spans than immigrants and had more stable families. Nevertheless, malaria remained an endemic disease through the 19th century and Maryland lifespans long lagged behind those in New England. In evaluating their actions, it is important to keep in mind the gamble they took and the harsh conditions they faced.

Medicine has made extraordinary advances in the past four centuries. Dentistry is a field that is often overlooked, but in terms of health and well-being, its progress is equally remarkable. One of the principal contributions of archaeology is the ability to better understand the lives of past people in a direct way. At the same time, by revealing the lives of these long-forgotten people, archaeology gives the 21st century a valuable perspective to more fully appreciate the tremendous progress that has been achieved in health and medicine since the first settlers arrived in a place they named Maryland.

About the Author

Dr. Miller is a Historical Archaeologist who received a B. A. degree in Anthropology from the University of Arkansas. He subsequently received an M.A. and Ph.D. in Anthropology from Michigan State University with a specialization in historic sites archaeology. Dr. Miller began his time with HSMC in 1972 when he was hired as an archaeological excavator. Miller has spent much of his career exploring 17th-century sites and the conversion of those into public exhibits, both in galleries and as full reconstructions. In January 2020, Dr. Miller was awarded the J.C. Harrington Medal in Historical Archaeology in recognition of a lifetime of contributions to the field.