Although the Brick Chapel has rightfully received the greatest attention, several other structures once stood in the Chapel Field. Some date to the early c. 1635-1645 mission, including the first wood chapel. Another is a structure called the Priest’s House. Located northeast of the Brick Chapel, and now marked by a ghost frame, it was long thought to be the 1660s church. In 1913, James Walter Thomas in his Chronicles of Colonial Maryland, described the chapel as a brick structure about 18 by 30 feet in size. The site was examined by Jesuit Father LaFarge in 1926, who described it as the old St. Mary’s Chapel. This understanding changed in 1938 when Henry Chandlee Forman discover the actual cross-shaped brick chapel which he described for the first time in his Jamestown and St. Mary’s: Buried Cities of Romance. It was Forman who named the smaller building the Priest’s House, due to its proximity to the Chapel and it having a cellar that indicates some type of domestic function.

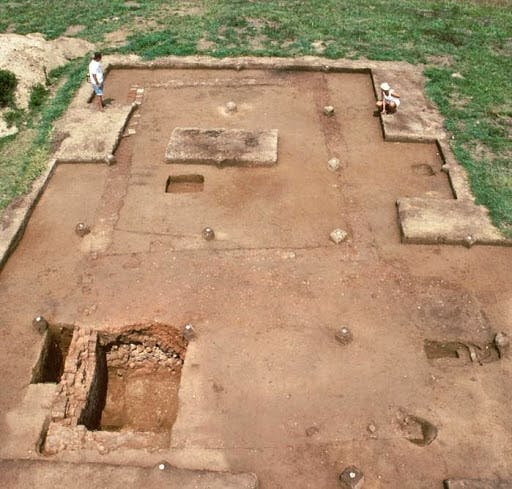

HSMC found the general location of this building in 1983 during a surface collection directed by Garry Wheeler Stone. Testing occurred in the early 1990s and building was fully uncovered in 1992. This shows the archaeological crew working on the site under the direction of Timothy Riordan.

Archaeologists working on the Priest’s House during the 1993 Field School.

Archaeologists working on the Priest’s House during the 1993 Field School.

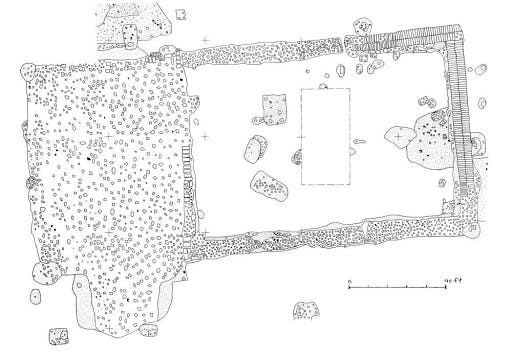

The excavations found that the structure was larger than previously thought, measuring 21.5 by 45.4 feet. It was at least partially of brick and had a cellar under one end, accessed by an external bulkhead entrance. The overall building is seen here along with the drawing of the archaeological remains.

Photo of the Priest’s House Foundation and the Archaeological Scale Drawing of the Building.

Photo of the Priest’s House Foundation and the Archaeological Scale Drawing of the Building.

Analysis of the foundation by Stone and Riordan found that it was built in two phases. One was the cellar structure that may have been first and then the north section. Among the evidence for Stone’s observation is that the cellar’s mason was left-handed but the northern addition’s mason was right-handed. Despite extensive effort, no chimney was found. Perhaps if only shallow footed, it’s base was plowed away. While the cellar was about five foot deep, the foundations remaining of the other part of the building were only one brick deep. As can be seen in the drawing, there were double bricks laid on their sides rather than flat, known as rowlock. Found at the base of foundations, a rowlock is stronger than bricks laid flat and suggests that the walls were fully brick rather than just a brick foundation. Bricks above this would be laid flat. However, during demolition, nearly all the brick above the row lock had been removed to either recycle or throw into the cellar as part of site clearance. Any remaining upper remnants of the foundation were later disturbed by plowing.

Examination of the artifacts around this building suggests it was built in the late 17th century. Domestic occupation was more intense in the c. 1700-1740 period, judging by the quantities of artifacts. This may be due to the structure becoming a mass house. After the Brick Chapel was officially closed by the government in 1704, mass could only be held in a domestic dwelling, as was the practice in England. Perhaps the building began as a one room 16 by 21.5 foot structure with a cellar used by the priest when in residence at the chapel and the northern portion was added after 1704. But why was a cellar needed? Alternatively, perhaps the two sections were constructed within a few months of each other but by different masons. Notably, the brick used in the Priest’s House construction is different from that used to build the chapel. Only very meticulous archaeological investigation can provide the evidence needed to resolve this question. In any case, the location of the building near the Brick Chapel, presence of domestic artifacts, and the evidence for continued burial in the Chapel cemetery may support the mass house interpretation in the early 18th century. Demolition of the building likely occurred in the c. 1740-1760 period, perhaps coinciding with the Jesuit’s selling the Chapel Field land in 1754.

To obtain data about the cellar, we excavated one corner of the cellar and a small outside section of one of its walls. This work encountered a mass of brick rubble and other architectural debris but few other artifacts, as seen here.

Top of the cellar with the jumble of brick rubble being exposed.

Top of the cellar with the jumble of brick rubble being exposed.

The excavators had to work through feet of rubble and other debris, obviously the result of demolition of the building. Aside from a few pipe fragments, nearly all the materials were of an architectural nature, including brick, mortar and nails. This picture shows the crew at work.

Digging through the brick layers in the Cellar of the Priest’s House.

Digging through the brick layers in the Cellar of the Priest’s House.

When they reached the bottom, the cross-section revealed the intense jumble of brick that has been thrown into the cellar. Only at the very bottom was a sandier soil mostly free of brick found.

Cross-section photograph of the cellar showing the dense rubble fill found by the excavators and one portion of the cellar’s intact brick wall on the left.

Cross-section photograph of the cellar showing the dense rubble fill found by the excavators and one portion of the cellar’s intact brick wall on the left.

Given this setting, excavators made a remarkable discovery about halfway down in the rubble. There, along the edge of the brick wall, their trowels uncovered something totally unexpected, a small intact glass bottle, as seen here. A part of its lip was missing but it was otherwise complete. And the lip fragment was not found in the cellar. Based on discussion with the excavators, it seems that a brick had been placed over the bottle location lying flat amid all the jumble of brick fragments.

Picture of the first bottle as uncovered by the excavator.

Picture of the first bottle as uncovered by the excavator.

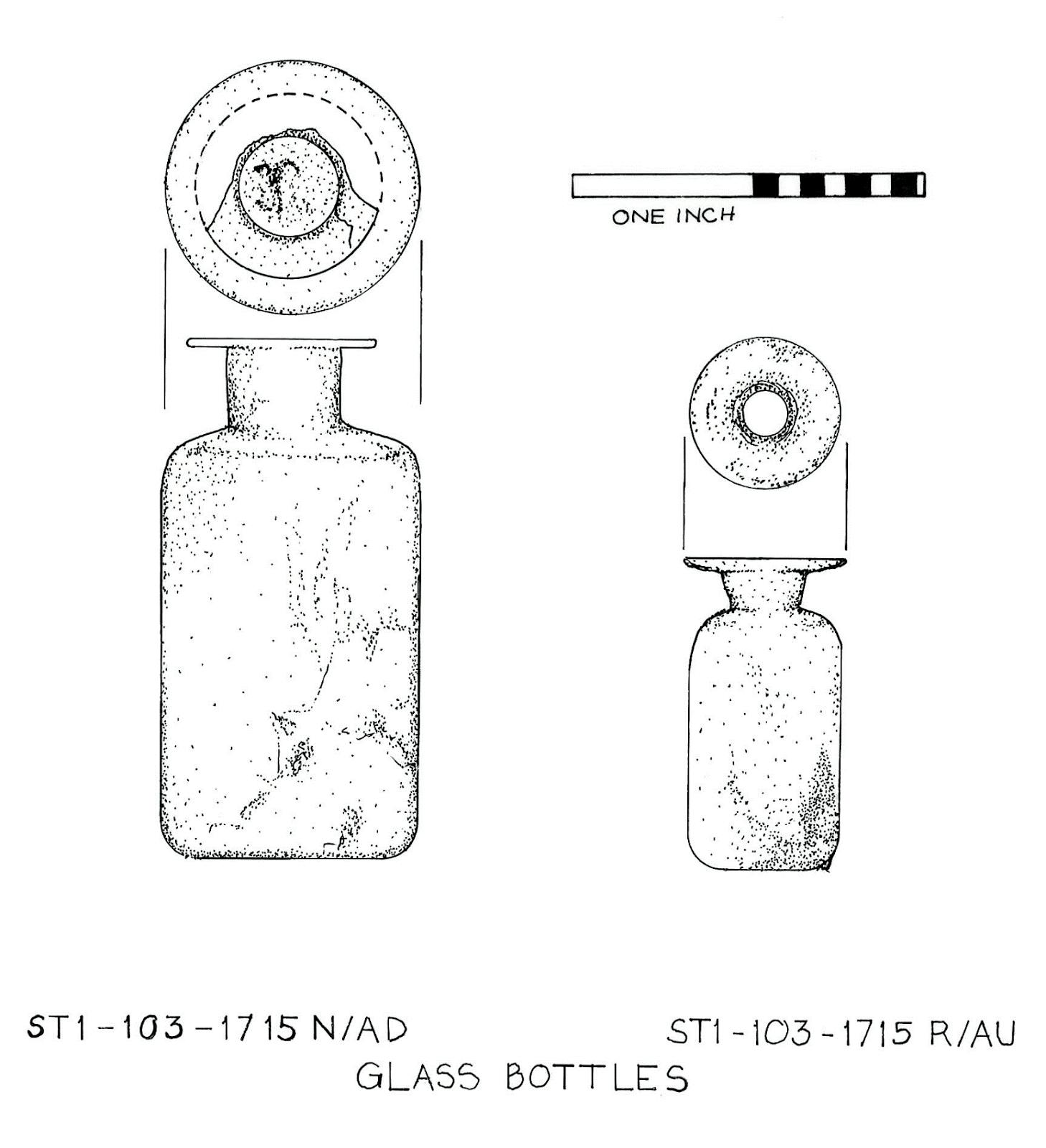

Work halted to photograph the find and then more dirt was removed. Next to the first bottle was a another, although much smaller. It was fully intact although very fragile. The two complete bottles are seen here.

Two Glass Vials from the Priest’s House Cellar. Photograph by Donald Winter.

Two Glass Vials from the Priest’s House Cellar. Photograph by Donald Winter.

How they survived in the midst of all the brick is unclear but it is truly remarkable. If thrown into the cellar, which was already partially filled with brick rubble, such fragile specimens would have surely broken. Finding two fully intact bottles makes it virtually impossible that they were casually tossed into the rubble filled cellar by workers. And finding them next to each other under a brick perhaps placed over them, implies intentionality. The drawing below shows their small size. They were blown in a pale green glass commonly used for vials and their surfaces show a beautiful rainbow array of colors due to their being buried for several centuries. While fragments of vials similar to the larger specimen have been recovered on other St. Mary’s City sites, the other one is unusually small.

Hand-blown glass vials were made for varied purposes in the 17th and 18th centuries. Because the basic shape and method of manufacture did not change, we can only date these to the period of site occupation from the late 1600s to mid-1700s, with the early 18th century being most likely. These are sometimes called apothecary vials as they were used to hold medicines and other substances, including perfume. Such small hand-blown glass vials go back to Roman times and they began being made again in England in the 16th century. Collector David W. Barker notes that it was also often a practice to place bottles and vials under the entry stone at a door to ward off evil spirits (See Barker http://www.theglassmuseum.com/Englishvials.html). Vials have been found in old buildings under hearthstones, beneath window sills, behind fireplaces and in crevices and niches for protection. Could these vials have been within the Priest’s House for a similar purpose, found by the crew during demolition? But why then give them any special treatment while tearing down the building?

Another use for such vials, and more in keeping with a Priest’s or Mass House function relates to sacred oils. In the Catholic Church, three oils are used. Each must be created by a bishop and then distributed to parishes. They are the Oil for Anointing the Sick, the Oil for Catechumens, and Holy Chrism. The oil for the sick is used in the sacrament formally called Extreme Unction (final anointing) for the dying, although that was extended to the sick in the 20th century. Individuals studying to become Catholics are anointed with the oil of Catechumens. Oils for the sick and catechumens are blessed olive oil. Holy Chrism is different, being a mix of olive and balsam oils. It is used in baptism, confirmation, ordaining priests, and the blessing of altars, churches and vessels used during mass.

Scale Drawing of the Two Vials. By artist Jatze Torres for HSMC.

Scale Drawing of the Two Vials. By artist Jatze Torres for HSMC.

An annual Chrism Mass is now held to create the three oils on Holy Thursday. The oil for the sick is blessed first, then that for catechumens and finally the Chrism. The last requires a different ritual for its creation and consecration. A bishop mixes the oil from a balsam plant with olive oil, breathes on the mixed oil to signify the presence of the Holy Spirit and then says a special prayer to consecrate it. Once blessed, these oils are no longer ordinary ointments but considered holy and gifts from God to the church and the people. Given the absence of a Bishop in the United States until John Carroll’s consecration in 1790, the sacred oils must have been imported for use in early Maryland. Perhaps these vials had been used to hold the blessed oils and left empty at the Priest’s House. An association with blessed substances would perhaps give the bottles more significance than a regular medicine bottle. Could this explain why they were placed in the cellar without being broken?

As with many archaeological discoveries, we cannot explain the why with any certainty. Perhaps they were found in a niche within the walls, intended as a protection against evil. But then why two when one would presumably have been sufficient for that purpose? Had they been used in religious rituals and left in the old Priest’s House? Or were they just old domestic bottles abandoned by the last occupants? In any case, we must wonder why still whole and usable bottles would be discarded instead of carried away. And then, why were they placed carefully enough so they would not be broken in the mass of brick rubble that filled the cellar rather than just being tossed in? Look again at the picture of the cross-section of the cellar fill to understand the improbability of their not being broken in such a setting. There was something unusual about these bottles. Maybe future excavation of more of the Priest’s House cellar will provide additional clues. In any case, they are remarkable survivors found in a place where such fragile objects never should have remained intact. And despite these unanswered questions, we can say without doubt that they are the most exquisite and beautiful tiny bottles ever found at St. Mary’s City.

About the Author

Dr. Miller is a Historical Archaeologist who received a B. A. degree in Anthropology from the University of Arkansas. He subsequently received an M.A. and Ph.D. in Anthropology from Michigan State University with a specialization in historic sites archaeology. Dr. Miller began his time with HSMC in 1972 when he was hired as an archaeological excavator. Miller has spent much of his career exploring 17th-century sites and the conversion of those into public exhibits, both in galleries and as full reconstructions. In January 2020, Dr. Miller was awarded the J.C. Harrington Medal in Historical Archaeology in recognition of a lifetime of contributions to the field.