One of the most melancholy aspects of Project Lead Coffins was finding the remains of a tiny baby buried next to the coffins of Philip and Anne Calvert. Archaeology told us that the child had been buried after the two adults and forensic anthropology indicated that Anne Calvert was too old and in such poor healthy that she could not be the mother. Nevertheless, their burial in the same location implied some family connection. This is that the baby remains looked like upon opening the lead coffin.

Smithsonian anthropologist Douglas Owsley the age of the child was about 6 months and it might have been a girl. The tiny bones also revealed that the baby suffered from severe Vitamin C and D and iron deficiencies, implying an inability to properly eat. Indeed, rickets may have been a primary cause of death. The reasons for these problems are unclear but being born in late fall and swaddled throughout the winter would have prevented the child’s body from naturally producing Vitamin D by exposure to sunlight. Pollen found in the coffin showed palynologist Gerald Kelso that the baby had died and been buried in the spring of the year, since he found quantities of well-preserved oak and pollen around the bones. But there are no records of a baby and the identity of this infant remained a mystery for the next quarter of a century.

Finally, advances in the DNA analysis of archaeological bone by Harvard geneticist David Reich in 2016 allowed him to finally extract DNA from the baby’s remains. This revealed that the child was actually a little boy and showed that he had a direct genetic connection to Philip Calvert. He was Philip’s son. All the evidence allows us to reassemble this sad story. Philip’s only child was born in November or early December of 1682. He died suddenly on 14 January 1683, knowing that at long last he had an heir. However, such was not to be for the baby only survived a few more months, with his severely weakened body giving up life in April or May of 1683. Soon afterward, the baby was buried next to his father, and in a rare lead coffin like him, as must have seemed appropriate.

So who was the baby’s mother? The few surviving historical clues indicate it was Philip’s second wife, a young woman named Jane Sewall. She was the daughter of Henry and Jane Lowe Sewall, who had immigrated to Maryland in 1661 with three children. Daughter Jane was born in the colony around 1664. Henry had risen to prominence and served on the Governor’s Council, but he died in 1665. The following year, Governor Charles Calvert married Sewall’s widow. Charles is seen below, as he looked in the 1680s. Philip married her daughter Jane a year or two after Anne’s death, when Jane was 16 or 17 years old. Philip was in his 50s and such marriages where not uncommon at the time. Documentation for the marriage no longer exists but a July 1, 1681 land record listing Philip and Jane Calvert tells us the marriage happened prior to that date. It result in some unusual family relationships. Philip’s nephew Charles Calvert had married the elder Jane, Jane’s mother. So the elder Jane was both Philip’s niece-in-law as well as his mother-in-law. And the young Jane was Philip’s wife, Charles’s aunt, and his step-daughter. It must have been a bit complicated.

Charles Calvert, the Third Lord Baltimore, who married jane’s mother.

Charles Calvert, the Third Lord Baltimore, who married jane’s mother.

A little over a year after Philip’s death, Charles Calvert, now the Third Lord Baltimore, found it necessary to return to England to defend the charter against William Penn. His wife Lady Jane Calvert and Philip’s widow went with them. What happened to Jane in England has been obscure until the 21st century, when research in England was conducted.

In a 17th-century letter book at the British Library, I came across two important pieces of correspondence about Jane Calvert. They indicate that around 1685, she became acquainted with Philip Stanhope, the Earl of Chesterfield (1633-1714). Stanhope was a debonair courtier who had been educated on the Continent, had numerous affairs, most famously with a mistress of Charles II – Barbara Villiers, and engaged in half a dozen duels. Among his several wives was Elizabeth Butler, daughter of the Duke of Ormond in Ireland. Although made Lord Chamberlain to Charles II’s Queen Catherine, the kings brother James “was smitten in love” with Stanhope’s wife according to the gossipy Samuel Pepys, causing considerable difficulties. Later Stanhope served James when he became king, the lustful episode forgotten.

Philip Stanhope, the 2nd Earl of Chesterfield

Philip Stanhope, the 2nd Earl of Chesterfield

One letter Stanhope wrote is entitled “To Mrs. Calvert Borne in Mary-Land and a Romanist.” Although undated, it was probably written in late 1685 or 1686. It definitely refers to Jane Calvert, since it says she was Maryland-born and Catholic. The letter implies that they had already been in correspondence and Stanhope promised to

“…follow your advice in making such an Allmanack as may please you, for in it shall be Festivals, and no Fasts, Tides of pleasure without Ebbes, no Eclipeses of light or beauty, but a might year for conjunctions and marriages….there will be a new disease the next winter, called the Maryland Feaver, which will endanger some officers of the Army. I could add much more, but this is enough on this subject til I have the happiness of seeing you again in our Dear Square (as you call it) which is often though on with pleasure, and your absence with trouble”.

“Our Dear Square” was Bloomsbury Square in London and it seems likely that Jane was living in the fashionable structure known as Southampton House which faced this square. The elegant building is seen below, as depicted in a 1682 map of London. It was at the time on the north end of London, near open land. Jane’s mother and her father-in-law, Lord Baltimore, had an apartment in this structure, explaining why she was there. It is probably at Southampton House that Charles Calvert received the news of the 1689 Rebellion in his colony.

Southampton House in London, 1682. Charles Lord Baltimore and his family lived here after his return to England in 1684.

Southampton House in London, 1682. Charles Lord Baltimore and his family lived here after his return to England in 1684.

The “Maryland Feaver” predicted by Stanhope may indicate that a number of military officers were in pursuit of the 22 year old Jane. As a young and quite wealthy widow, having inherited all of Philip Calvert’s considerable Maryland estate, she would certainly have had a variety of eligible suitors. And given his amorous history, it is possible that Stanhope had some romantic intentions as well. But he was also helpful for in a June 2, 1686 letter, Stanhope notes that Jane had followed his advice by entrusting a Mr. Sergent Bigland to manage her finances, saying “I am confident that your money will be very secure in his hands, for hee hath long had the reputation of an honest Gentleman.” Such assistance was needed as the Bank of England did not yet exist, only being founded in 1694. Such financial transactions led to another unexpected clue about Jane.

In examining the Calvert Papers at the Maryland Historical Society (now the Maryland Center for History and Culture), I came across one document of particular relevance. It is a deed of trust for payment of debts made in London between a Thomas Bagshaw and John Thompson and Jane Calvert and dated November 26, 1691 (Calvert Papers No. 111). This has long been attributed to Lady Baltimore, the wife of Charles Calvert. But she would have been signed it as Lady Baltimore. Instead, evidence strongly implies that this is an agreement made by Philip’s widow Jane. This may be the only example of her signature and seal to survive, as seen here.

Signature and Seal of Jane Calvert, signed on 26 November 1691 in London. Document is in The Calvert Papers No. 111. Courtesy of the Maryland Center for History and Culture.

Signature and Seal of Jane Calvert, signed on 26 November 1691 in London. Document is in The Calvert Papers No. 111. Courtesy of the Maryland Center for History and Culture.

Her handwriting is very legible and the seal is most curious. As previously noted in Clues No. 21, seals were a vital mark of identity in the seventeenth century. They could be initials or symbols of varied kinds the person selected. In this case, Jane used the image of classical figure for her seal, as this closeup image shows.

Jane Calvert’s Was Seal

Jane Calvert’s Was Seal

But who does this represent? After examining many portraits of classical persons, the closest match seems to be the Roman poet Ovid. Ovid was one of the premier poets of the Roman empire, best known for his Metamorphoses, completed around 8 A.D. It is a compilation of mythology. But he is equally well known for his erotic writings and love poetry. These include The Heroines, The Loves, The Art of Love and The Cure for Love

The Roman Poet Ovid

The Roman Poet Ovid

.

Ovid was very popular throughout the Medieval period and Renaissance and in the 17th century. One scholar says that he delighted in physical beauty and physical love, was sentimental, and found the greatest tragedy in the frustration of love by cruel fate. It seems possible to conclude that Jane Calvert was attracted to such literature, as she had certainly suffered cruel fate in the lose of her husband and child. This is the only clue we have into the mind of Jane Calvert.

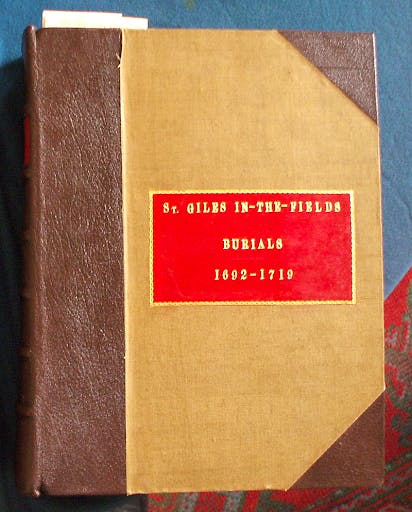

So did Jane find new love in London? Sadly, the evidence indicates otherwise. I was given permission to examine the original burial registers at St. Giles in the Fields in London. This is an early 18th-century church build on the older 16th-century foundations. It became a principal burial ground for that portion of London, including Catholics, other non-conformist, the indigent and executed prisoners. We know that both John Lewger and Cecil Calvert were interred here. Given later burial and commercial development, the locations of their graves are unfortunately forever lost.

St. Giles in the Fields, London, and the Original Burial Register for 1692 to 1719.

St. Giles in the Fields, London, and the Original Burial Register for 1692 to 1719.

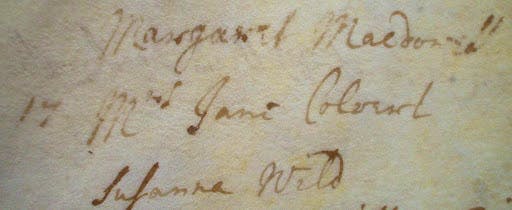

In the burial book beginning in 1692, there is a notable entry. It was made on May 17, 1692 and lists the interment of a “Mrs. Jane Calvert”. This tells us she never remarry and was still Philip’s widow nearly a decade after his death.

Burial Registry for Mrs. Jane Calvert, 17 May, 1692. St. Giles in the Field’s Parish, London. Courtesy of St. Giles in the Fields Vestry.

Burial Registry for Mrs. Jane Calvert, 17 May, 1692. St. Giles in the Field’s Parish, London. Courtesy of St. Giles in the Fields Vestry.

Thus ends the story of Maryland-born Jane Calvert. With her grave location now lost, all that survives about this young woman is a copy of her will, a Maryland land record, the two Stanhope letters, the burial entry, and the lead-encased remains of her infant son at St. Mary’s City. It is a somber story only brought to light by the discovery of the lead coffins and advances in archaeological science, but it gives us a new perspective on life in the seventeenth century for one young woman.

About the Author

Dr. Miller is a Historical Archaeologist who received a B. A. degree in Anthropology from the University of Arkansas. He subsequently received an M.A. and Ph.D. in Anthropology from Michigan State University with a specialization in historic sites archaeology. Dr. Miller began his time with HSMC in 1972 when he was hired as an archaeological excavator. Miller has spent much of his career exploring 17th-century sites and the conversion of those into public exhibits, both in galleries and as full reconstructions. In January 2020, Dr. Miller was awarded the J.C. Harrington Medal in Historical Archaeology in recognition of a lifetime of contributions to the field.