Fishing is a very popular activity for Marylanders today, enjoying the bounty found in the Chesapeake Bay and the rivers and streams of the state. Was this also the case in the seventeenth century? If so, what fish were popular and how did people catch them? History provides only a few clues in answering these questions so we must turn to that other sources of evidence, the archaeological record. By identifying the thousands of animal bones found on sites, it is possible to learn about many aspects of the colonial diet including fish. Reconstructing the diet of the settlers over the 17th and 18th centuries was the focus of my doctoral dissertation back in the last century and that yielded new insights about fishing. Some of those findings are shared here.

The HSMC excavations at the St. John’s site produced the first animal bone samples studied from seventeenth-century Maryland. These came from deposits in cellars and pits that spanned the 1638 to c. 1715 habitation of the site. Here is one of the pits while half excavated. It was dug for daub but then filled with kitchen waste from the St. John’s kitchen. It was a superb “time capsule” of life at St. John’s in the 1660s.

Pit 50M/50P at St. John’s. It was filled with St. John’s kitchen waste in the 1660s

Pit 50M/50P at St. John’s. It was filled with St. John’s kitchen waste in the 1660s

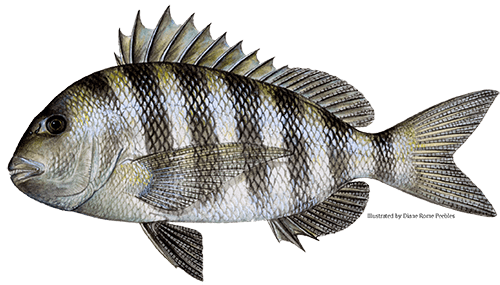

The first surprise was how prominent were fish bones in the early samples. Thee early samples from St. Johns averaged 37% fish bone, and the 1640s-1650s deposit from Pope’s Fort in the Town Center yielded 34.2% fish bone. The bones are identified by comparing them to modern skeletons of many different species. In identifying the bones, it was surprising to find that one fish overwhelmingly predominated – the Sheepshead. It looks like this.

The Sheepshead Fish (Archosargus probatocephalus)

The Sheepshead Fish (Archosargus probatocephalus)

Bones of this fish make up between 29% and 45% of the total identified elements from early Maryland sites. Its distinctive bones are shown below. The Sheepshead has sharp spines that look like sharpened needles and can easy draw blood even after 300 years in the ground. Their jaws display many small circles that once held pearl like teeth with which to crush and eat their favorite food, mollusks and crustaceans. You can see several of these jaw bones in the picture here.

Bones form the Sheepshead found in the moat of Pope’s Fort, 1645-1655.

Bones form the Sheepshead found in the moat of Pope’s Fort, 1645-1655.

The Sheepshead also has stout incisors in the front that look like human incisors to some extent. One story is that the fish got its name because of the resemblance of its front teeth to those of sheep, who also have prominent incisors. In any case, the name sheepshead was commonly used by 17th-century colonists. With powerful jaws, they can grab and penetrate small oysters, clams and other shellfish. Oysters, barnacles, clams, shrimp and other crustaceans are the preferred food the sheepshead, and much of the St. Mary’s River bottom was covered with oysters and other shellfish in the 17th century. This picture shows the incisors and pearl-like grinding teeth of a live specimen.

A live Sheepshead showing its dentition

A live Sheepshead showing its dentition

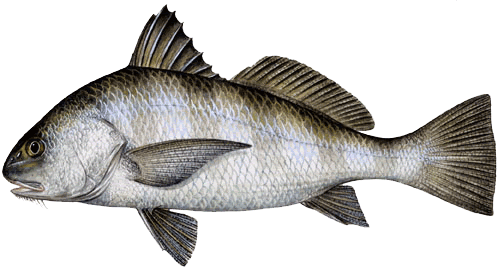

Although the Sheepshead is by far the most common, other fish identified among the thousands of bones in the early deposits are Black Drum, Red Drum, White Perch, some Sturgeon, Longnosed Gar, one Toadfish and occasional crab claws. Crab remains do not survive well in the ground, requiring specific low acidity soil conditions, so the few specimens found likely represent what was once many more remains. Sturgeon were not prominent in the areas near Chesapeake Bay but were taken in much greater quantities on the upper James and Potomac Rivers, probably when they spawned there.

A Black Drum. They can weight over 100 pounds and were eaten in St Mary’s City.

A Black Drum. They can weight over 100 pounds and were eaten in St Mary’s City.

Using an analytic procedure to determine how much meat different animals would have provided to the diet, samples shows that Sheepshead contributed from 4% to 6% of the total meat, and seasonally it was probably much more important. Overall, fish made up from 6% to 13% of the total meat consumed at early St. Mary’s City sites. Several of these species are only presented in the April to October period in the Chesapeake and the Colonial diet in the spring/summer must have included fish on a regular basis.

The exceptional quantities of Sheepshead found in the deposits came as a real surprise, for they are virtually extinct in Chesapeake Bay today. This was the case when I began trying to collect fish skeletons for a comparative bone collection in the mid-1970s. No Sheepshead were being caught in the Maryland part of the Chesapeake Bay, something confirmed by local fisherman Thomas Courtney, who generously assisted me in obtaining other species. Only near the mouth of the Chesapeake are Sheepshead occasionally found with any frequency, as well as along the Atlantic coast. This contrasts greatly with the coastal Carolinas and especially the Gulf coast of Florida where Sheepshead are still abundant. It was in Florida where I was finally able to obtain sheephead bones for the collection. But this was apparently not a recent phenomenon. In a significant 1928 study Fishes of Chesapeake Bay by Samuel Hildebrand and William Schroeder, they wrote the following about the Sheepshead:

“The sheepshead is taken in the Chesapeake in very limited numbers, from the Rappahannock River Southward. In 1920 the catch was only 863 pounds, worth $129, all taken in pound nets. Some years ago this fish was an important commercial species in the bay, but the catch gradually diminished, until at the present time the species has almost entirely disappeared.”

But they reported that of those that were caught, they were large, ranging from 5 to 15 pounds in weight. And the most commonly used bait was small crabs. Compared to the 863 pounds of Sheepshead caught in 1920, they wrote that in that same year 1,040,274 pounds of Striped Bass, 1,130,590 pounds of Croaker, 1,816,346 pounds of Shad, and 535,080 pounds of White Perch were caught. Sheephead were clearly insignificant in the Chesapeake Bay by the early 20th century.

But if one turns to an 1876 fisheries study, it says that Sheepshead “Frequent the oyster localities of all parts of the Chesapeake Bay”. What happened? The major estuarine event that occurred between the end of the Civil War and 1920 was the massive extraction of oysters from the Chesapeake. Indeed, the Bay became the world’s largest producer of oysters during that time. The introduction of dredging equipment instead of acquiring oysters by raking or hand tonging had a huge impact. The stable bottom environment was disturbed in areas never previously impacted and literally billions of oysters were removed from the Chesapeake. This had serious environmental impacts for the estuary. The disappearance of the Sheepshead is probably one notable consequence of this change. Indeed, given the archaeological evidence, it is possible to propose that the Sheepshead can serve as a powerful indicator species of stable, healthy estuarine environments.

Archaeology attests to the abundance of Sheepshead in the colonial Chesapeake. Analysis of Virginia sites along the Bay have also found large quantities of Sheepshead bones. One historical document supports this assertion Thomas Glover, a traveler to Virginia in 1676, wrote that “A Planter may often take 12 or 14 [Sheepshead] in an hours time with hook and line.” Using the 5 to 15 pound per sheepshead estimate of Hildebrand and Schroeder, that is a whole lot of fish for very little effort. No wonder they were so popular. And from all reports, the Sheepshead is an excellent tasting fish.

A person familiar with Chesapeake fishing today will observe how different the catch is. Most popular today are Striped Bass or Rockfish, Bluefish, Black Sea Bass, Croaker, Spanish Mackerel, Spot, Spotted Sea Trout and White and Yellow Perch. Only a few of these are present in 17th-century deposits. Were these fish far less abundant in past times? That seems unlikely since Spot and Croaker have been identified at Virginia Indian sites, along with Striped Bass and Perch. So why do we not see them in Colonial sites?

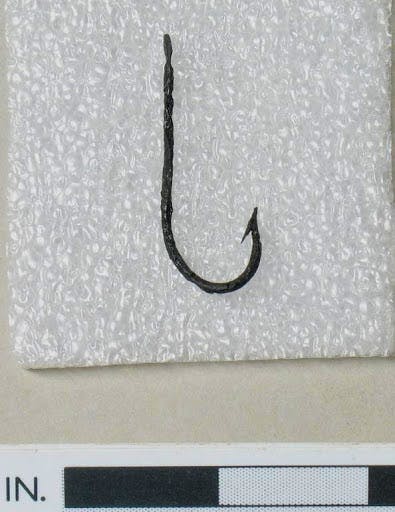

The answer is probably found in how colonists were fishing. We very occasionally recover fishing hooks during the excavations, with one good example found at the Leonard Calvert House site shown here.

Fish Hook recovered from the Leonard Calvert Site. Probably a Sheepshead hook

Fish Hook recovered from the Leonard Calvert Site. Probably a Sheepshead hook

More insight comes from the probate inventories of colonists. A sample of 900 households dating between 1640 and 1740 were examined and 95% of those had only one type of fishing gear – hooks and lines. A few had fish gigs or tridents, and some among the 5% had nets. This suggests that if you fished in early Maryland, you most likely relied upon hooks and lines, not nets, poles and certainly not rods and reels. And the more detailed inventories even classify the hooks by three sizes – Perch, Sheepshead and Drum hooks. This matches perfectly with the main species recovered from archaeological sites. And curiously, few of the homes had boats or canoes. This implies that fishing was often done from the shore, using a form of bottom fishing. The person would stand on the shore or in shallow water, twirl the baited hooks and weight and when at a high speed, cast it out into the water. The hooks would sink to the bottom where they would attract bottom feeders called benthic species. The line could then he held or tied to a tree or stake to await a bite. I know this works because as a young boy, my grandfather took me fishing for catfish on the Arkansas River using this exact same technique. The picture below shows the actual gear he had been using for years, and it is probably very similar to that of 17th-century colonists in Maryland. They likely added another hook or two and perhaps used a lead weight.

Traditional Bottom Fishing Gear of Hook and Line, Arkansas, c.1955.

Traditional Bottom Fishing Gear of Hook and Line, Arkansas, c.1955.

Knowing this gives us an important insight. By using such gear, colonists were selecting fish species that fed on the bottom, including Sheepshead, Black Drum, Red Drum, White Perch, sometimes Striped Bass and even oyster toadfish. Fish that feed in the upper water column, called pelagic species, such as Shad, Herring, Bluefish, Sea Trout, etc. are rarely caught with bottom fishing gear. Thus, the absence of these fish in the archaeological deposits is not due to their absence in the Chesapeake but rather to the way the colonists were fishing, focusing on the bottom environment. But it is strange that popular fish today such as Spot or Croaker are not in the bone samples from sites. I have not been able to explain that.

The first Bluefish and Herring bones are not found until the mid-18th century in St. Mary’s City. Inventories from that time show that wealthy planters were acquiring larger seine nets that required a labor force to operate. This allowed a much larger range and quantity of fish to be caught, with them being increasingly being salted and barreled for provisions. One well know example is George Washington who had his enslaved work force net herrings and shad in the Potomac. Individuals such as John Hicks and William Deacon also seem to have used nets at St. Mary’s City in the 18th century.

Fishing in the 17th-century was far different than today. During this the time Izakk Walton published his The Compleat Angler (1653), and in the decades after the English Civil War, fly fishing became a popular pastime for gentlemen in England. A pole and line with live or artificial bait was used. However, there is no firm evidence that people fished like that in Maryland, although it is possible a few did. Poles or rods are not mentioned in the inventories with fishing equipment. Instead with very simple gear, a planter could apparently take quantities of fish with little time or labor. Fish were especially important to the diet during the warmer months of the year, with a major emphasis upon the tasty Sheepshead. It is obvious that fish were exceptionally abundant in the waters of the Chesapeake Bay.

Given all that, the archaeology has revealed a major puzzle. The use of fish declines radically. At St. John’s in deposits from the c. 1640-1680 period, fish bone makes up 39.9% of the total bone, but in the 1680-1715 deposits, it is only 2.98%. This drop in fish usage is found on numerous other sites in Maryland and Virginia. Why would such a readily available food source not be used? I cannot answer that. The abundance of fish did not dramatically decline. The only explanation I have been able to offer is that domestic animals became so successful and readily available that the diet shifted to them for meat. Fish and Oysters and Crabs were still eaten, but in nothing like the large quantities consumed in the first three or four decades on Maryland.

Perhaps the most spectacular fishing artifact found at St. Mary’s City so for is a large iron trident from an early 19th-century context at the Tabb’s Purchase site. This photograph shows it being treated by conservator Lisa Young. It is big and sharp and was obviously meant for larger fish like the Black Drum or Sturgeon, although it could also capture larger Sheepshead, Striped Bass or other fish such as flounder. Tridents are listed in 17th-century inventories but none of that era have yet been found in our excavations.

Fish Trident from The Tabbs Purchase site in St. Mary’s City, perhaps late 1700s.

Fish Trident from The Tabbs Purchase site in St. Mary’s City, perhaps late 1700s.

Some evidence about fishing and fishing methods comes from the legal record. In 1678, an act was passed that prohibited work and gaming on Sundays by everyone, “absolute works of necessity and mercy always Excepted.” This was to maintain the Lord’s Day as a day of rest and worship. Included in the act is an important statement about fishing. Apparently, “itt hath been Customary for such sort of persons to Spend the said day in the bodily Exercise or occupacon of fishing.” So fishing was apparently a popular Sunday activity for some colonist. The Assembly therefore ordered that:

“noe person or persons whatsoever Inhabitant or Forraigner shall from & after the time aforesaid uppon any Lords day as aforesaid presume to take fish in any Bay Port or Creeke of or belonging to this Province with any Netts Tramells saines Hookes or Lines or any other instruments of fishing nor shall Cofnand willfully Suffer or permitt any of his or their Children hired servants servants or Slaves soe to fish as afore-said…” (Archives of Maryland 7:51-52).

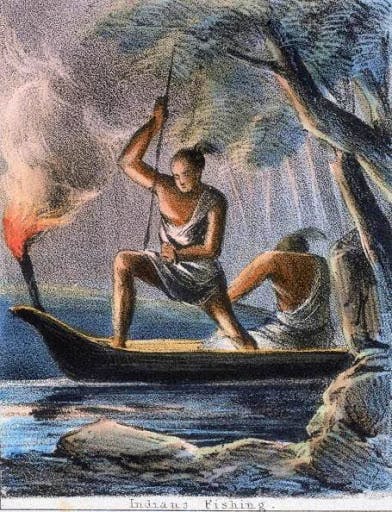

A tramell net is a multi-layer net that is suspended in the water and fish are caught by their gills. The saine (seine) net is larger, requires several people and corrals fish as the net is pulled to the shore. In 1694, an act prohibiting striking fish in Dorcheseter and Somerset Counties was passed, apparently because many fish were needlessly harmed with this method. However, citizens of those counties asked it to be repeal in 1696. It came up again in 1704 as “The Aggreivance related to Striking Fish” but the legislature concluded it was not an aggrievance. Eight years later it was judged to actually be a problem and the 1712 act provides new details about one type of fishing in Maryland.

“Whereas the frequent Striking of Fish within the Precincts of this Province, has been represented to this present General Assembly, as a great Evil to the Inhabitants thereof, in the Destruction of their Fishery; Be it therefore Enacted by the Queen’s most Excellent Majesty, by and with the Advice and Consent of Her Majesty’s President, Council, and Assembly of this Province, and the Authority of the same, That no Person whatsoever shall hereafter strike or shoot any Fish within the Precincts aforesaid, with Gigs, Arrows, or any other striking Instruments, nor shall presume to go out upon the Water in Canoes, Boats, or other Vessels fit for that Purpose, in the Night time, provided with Lights, or other Utensils for Striking,..”

Fines were set a 200 lbs. of tobacco for use of such a boat and 100 lbs. of tobacco for each fish struck. Half the fine would go to the informer and the rest to the government. But this did not apply to all sea creatures nor to Atlantic waters, as the act concludes with

“…Provided nevertheless, That this Act, or any thing therein contained, shall not extend, or be construed to extend, to hinder or debar any Persons whatsoever, from Striking Whales, Sharks, Porpoises, Sturgeon, Stingraes, Skates, or Garfish, in the Day-time, within the Precincts aforesaid, nor any other sort of Fish, at any Time, upon the Sea-side. Pass’d November 15th 1712” (Archives of Maryland 29: 197-199).

The gig is a trident or similar device mounted on a long pole. This law shows that tridents or multi-prong spears and arrows were being used. And some colonists were engaged in night fishing by which a fire or lantern in the bow of the vessel would attract fish that could be struck. This is the earliest evidence in Maryland records about such a practice but it is known that Chesapeake Bay Indians used this method. The picture below is one depiction of fishing from a log canoe. It is possible the English learned this method from the Yaocomico in 1634. While there is sparse documentary evidence, it seems very probable that both daytime and nighttime fishing was conducted by the Maryland colonists.

Painting of American Indians Night Fishing in a Log Canoe. 1845, Getty Images.

Painting of American Indians Night Fishing in a Log Canoe. 1845, Getty Images.

Despite the good intention of the 1712 law, it was repealed a few years later because it proved ineffective due to the difficulty of enforcement. But such a practice was apparently widespread enough in the colony that such a law was considered needed.

Fish were a vital element in the diet of Maryland colonists, especially in the warmer months of the year. If you lived in early Maryland, there is no doubt that you would have eaten Sheepshead and Drum on a fairly regular basis. Archaeology has thus revealed a part of the Maryland story about which the documents are silent. But beyond diet, the recovery of animal bone from well dated sites provides valuable new information about how the Chesapeake Bay has changed over the centuries. In particular, this research indicates how significant the Sheepshead is as indicator species for evaluating estuarine stability and health over long periods. Oysters are another significant environmental indicator and how they went from being an excavator’s nuisance to a new window on the past will be subject of a future Clues. All our digging makes is clear that the bounty of the Chesapeake Bay has long been a source of culinary enjoyment for people living here and that has not changed over the centuries. Indeed, fish, crabs and oysters remain an integral part of Maryland culture and identity down to the present day.

About the Author

Dr. Miller is a Historical Archaeologist who received a B. A. degree in Anthropology from the University of Arkansas. He subsequently received an M.A. and Ph.D. in Anthropology from Michigan State University with a specialization in historic sites archaeology. Dr. Miller began his time with HSMC in 1972 when he was hired as an archaeological excavator. Miller has spent much of his career exploring 17th-century sites and the conversion of those into public exhibits, both in galleries and as full reconstructions. In January 2020, Dr. Miller was awarded the J.C. Harrington Medal in Historical Archaeology in recognition of a lifetime of contributions to the field.