To prove your identity, especially on important documents, people in the 17th century required more than a signature because signatures could be easily forged. The solution was an ancient one – having a personal seal. Ancient civilizations of the Near East and Egypt had developed seals to be impressed in clay and this concept using metal stamps or signet rings was continued amongst the Greeks and Romans. In the Medieval era, monarchs, princes, the Pope, Cardinals and Bishops each had seals, as increasingly did towns and some corporations. The oldest surviving town seal in England dates to 1091 and is for the charter of the city of Oxford, as seen here, showing an oxen at the river ford. Great Seals were developed for royal and ecclesiastical degrees and grants (See Clues Number 15 for a discussion of Maryland’s Great Seal).

Seal for the town of Oxford issued in 1091, the oldest in England.

Seal for the town of Oxford issued in 1091, the oldest in England.

But there was also a need for individuals to have a means of certifying that a document was from them or it met with their approval. Thus, the individual signet ring or stamp became widely used. These were generally small devices of metal that displayed an engraved personal monogram or distinctive decorative device that would leave a unique design. It was pressed into melted wax to create a wax seal or onto a wafer of paper to impart the impression. By the 17th-century, lesser nobility, freemen and even some commoners had a personal seal of some type.

Wax seals were used to close letters or be placed beside a signature to verify it. A 1675 painting by Flemish artist Cornelis Norbertus Gysbrechts shows period letters closed with a red wax seal and another seal verifying a signature.

Painting with Letters called “Quodlibet” by Cornelis Norbertus Gysbrechts, 1675.

Painting with Letters called “Quodlibet” by Cornelis Norbertus Gysbrechts, 1675.

Envelopes were not used until c 1840 and self-sealing ones were not invented until the mid-1850s. A 17th or 18th-century writer would therefore have to compose their message on a sheet of paper, fold it into a small packet, write the name and address of the recipient on the exterior and seal up the letter with wax and their signet ring or metal stamp. The wax seal could not be easily removed without breaking it, thus helping ensure that the correspondence had reached the intended person without it being read by others.

I had the privilege of meeting with one of England’s premier experts on seals -David Morris- to help evaluate Maryland’s Great Seal, and he said that the wax itself changed over the years. In medieval times it was mostly beeswax and turpentine, mixed with red lead. By the late 1500s, the beeswax was replaced by a mixture of Venice turpentine (an extract of the larch tree) and shellac, which made a harder and shinier material than beeswax. Chalk and resin were sometimes added in varying amount and red lead remained a coloring agent. Red was a common color although dark brown and black were also used. Black was associated with death and I have seen some period wills sealed in this color. In the 19th century, a “Language of Colors” developed with black for death notices and mourning, white for engagements and wedding announcements, chocolate brown for dinner invitations, and blue for love letters. But such was not the case during the colonial era in America.

The first personal seal found at St. Mary’s City was during the excavations in the early 1970s at the St John’s Site. It was a metal stamp that bore the initials “RM” accompanied by floral decoration. This shows the seal itself and the decorative handle. The other picture shows the full face.

The brass “RM” Seal recovered from the St. John’s site in the early 1970s.

The brass “RM” Seal recovered from the St. John’s site in the early 1970s.

Despite have the vital clue of the two initials, no one directly associated with St John’s had such a name. However, Curator Silas Hurry has suggested that this seal could have belonged to a prominent citizen of St. Mary’s City, Richard Moy. Moy was an innkeeper and merchant who operated the Country’s House ordinary between 1672 and his death in 1675. He and his wife were buried inside the Brick Chapel. Another seal with the same handle but displaying a cluster of arrows has also been found during the excavations.

Archaeologist discovered a different type of seal during the 1990s excavations at the Cordeas Hope site in the center of St. Mary’s City. It is actually a multifunctional object being a signet seal, a ring, and a tobacco taper at the other end, as seen here. It lacks initials and displays a standing animal, perhaps a dragon or lion. This is a more generic type and similar specimens have been found several times in England. There is probably some status distinction here with the “RM” seal more custom made and the tamper seal produced in larger quantities. As will be seen, individuals with some social status had unique seals made to signify their identity.

The Ring Seal and Tobacco Tamper found at the Cordea’s Hope site. The closeup image shows the animal in more detail.

The Ring Seal and Tobacco Tamper found at the Cordea’s Hope site. The closeup image shows the animal in more detail.

For most individuals, the seal matrix does not survive. One can better find evidence of their personal choices for an identifying seal by examining the original documents to which the wax seal was attached. These can be found in the British National Archives, County Records offices and libraries such at the Bodleian at Oxford, with some at the Maryland State Archives and institutions such as Pratt Library and the Maryland Historical Society. Many have been lost, leaving only red wax traces of their former presence, or are broken. But a surprising number survive intact.

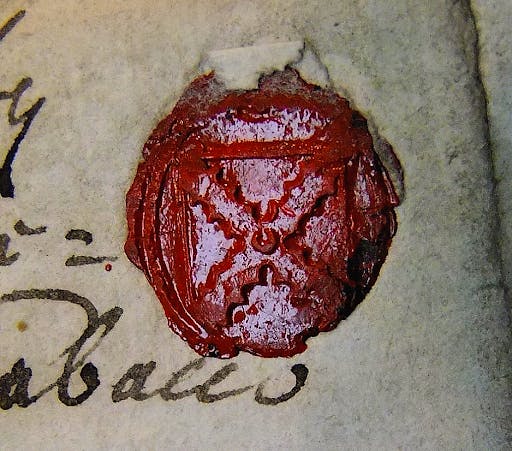

An example that is directly related to early Maryland is the seal of Jerome Hawley. He along with Leonard Calvert and Thomas Cornwallis led the founding expedition of the colony. And Hawley along with John Lewger, authored for Lord Baltimore the very significant A Relation of Maryland in 1635. However, the following year, Hawley campaigned for and received the position of the Treasurer of Virginia. It is a 1636 letter about tobacco in the British National Archives that still bears his seal, as seen here.

Jerome Hawley’s personal seal on a document in the British National Archives dated 1636

Jerome Hawley’s personal seal on a document in the British National Archives dated 1636

It is rather surprising because the design is what is called in heraldry a saltire raguly or a cross with ragged edges. Since medieval times, this form has been known as the Cross of St. Andrew. While the St. Andrew’s cross was and is a proud symbol of Scotland, the saltire raguly was the cross of Burgundy in France and the flag of the Spanish Empire in the 17th-century. It is therefore not a seal we would normally expect for an English gentleman and a bit of a mystery why Hawley chose this for his personal mark.

The seal of a renowned but now largely forgotten person is Sir Kenelm Digby. He was skilled in many things, an early scientist, astrologer, courtier, collector of legends and recipes, and chancellor to Queen Henrietta Maria. He was educated in Oxford at the same time Cecil Calvert was studying there. Digby traveled extensively on the continent, was good friends with Rene Descartes, represented English Catholics, and almost certainly knew and interacted with Lord Baltimore. He was also a close friend of Thomas White, the uncle of the man who would design St. Mary’s City. Digby was one of the founders of the Royal Society and authored its first scientific publication, A Discourse Concerning the Vegetation of Plants (1661), in which he proposed the vital role of oxygen for plant growth and presented a theory for plant photosynthesis. After his death in 1665, on his tomb stone was carved these words:

Under this Tomb the Matchless Digby lies; Digby the Great, the Valiant, and the Wise: This Ages Wonder for His Noble Parts; Skill’d in Six Tongues, and Lear’d in All the Arts.

Digby’s personal seal is seen here which consists of an elegant fleur-di-lie on a shield.

Seal of the Virtuoso and early Scientist Kenelm Digby

Seal of the Virtuoso and early Scientist Kenelm Digby

A man who played a vital important role in Maryland’s initial founding was Virginia governor John Harvey. Despite the strong hostility of prominent Virginians, Harvey followed the King’s orders, gave essential support to Lord Baltimore’s expedition and even visited St. Mary’s City soon after it was selected as the seat of the new colony. Obtaining supplies and livestock without his assistance would have been extremely difficult given the staunch opposition of the Virginians. His seal is found on a document written in 1635 and shows a classical profile of a Greek or Roman man, perhaps indicating his appreciation for the Classical world that had been renewed by Renaissance. He was a capable governor who tried to diversity the colonial economy. Appointed in 1628, he ran into conflict with the Governor’s Council who sought to retain power. In part due to the valuable assistance he gave to the Marylander’s, he was overthrown in 1635 but reappointed by Charles 1. The Council finally succeeded in his removal in 1639.

Seal of Virginia Governor John Harvey on a 1635 letter.

Seal of Virginia Governor John Harvey on a 1635 letter.

Another Virginian who played a role in the success of the early colony was Richard Kemp, Secretary of State for Virginia. He aided the Marylanders and even sent a flock of sheep to St. Mary’s City for Lord Baltimore. His seal is found on a January 1638 letter sent to Lord Baltimore from Virginia, as seen here.

Seal of Secretary of State Richard Kemp, placed on a letter written in January of 1638.

Seal of Secretary of State Richard Kemp, placed on a letter written in January of 1638.

Finally, I show the personal seal of Humphrey Waring who used the alias of Humphrey Ellis. The reason for this is that he was a Catholic priest, head of the London Chapter of the clergy and the personal chaplain to Cecil Calvert. Priests routinely used aliases to make it more difficult for them to be identified by authorities since priests in England were officially banned. He lived in Lord Baltimore’s home. After John Lewger left Maryland in 1648, he became a Catholic priest and was Calvert’s chaplain until his death in 1665 during the plague in London. Waring apparently became the new chaplain not long afterward and continued in the role until Cecil Calvert died in 1675. His seal is seen here, displaying three lions on a shield.

Humphrey Waring’s seal in 1676. He served as Lord Baltimore’s personal chaplain.

Humphrey Waring’s seal in 1676. He served as Lord Baltimore’s personal chaplain.

As can be seen, each of these seals are different and meant to be the unique signifier of a person. It is hard to determine the reason why people selected a specific design for their personal seal but individuality was certainly an important factor. They were an essential tool to verify authenticity in 17th-century life and provide subtle but valuable clues about how a person both perceived and represented themselves. What about the Calvert family and their seals? Did they follow this same practice? That is a story for a future edition of Clues.

About the Author

Dr. Miller is a Historical Archaeologist who received a B. A. degree in Anthropology from the University of Arkansas. He subsequently received an M.A. and Ph.D. in Anthropology from Michigan State University with a specialization in historic sites archaeology. Dr. Miller began his time with HSMC in 1972 when he was hired as an archaeological excavator. Miller has spent much of his career exploring 17th-century sites and the conversion of those into public exhibits, both in galleries and as full reconstructions. In January 2020, Dr. Miller was awarded the J.C. Harrington Medal in Historical Archaeology in recognition of a lifetime of contributions to the field.