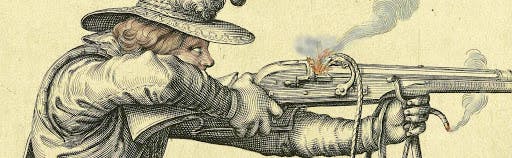

When settlers came to Maryland, they carried the most advanced firearms available. Europeans had long used guns that were fired by a burning rope or “match” and called a matchlock, as is seen in use here.

It was an effective weapon and used by the British and European armies until the early years of the 18th century. Its drawbacks included the continual effort to keep the match lit, the problem of light being given off in nighttime actions, and the great challenge of firing the gun in the rain. Consequently, efforts were made to develop a more reliable and less cumbersome weapon. Gunsmiths found the solution in the late 16th century when they invented the flint ignition system. This new system worked by having a specially shaped flint in a holding device called a hammer. When the trigger was pulled, the hammer would snap forward, causing the flint to strike an iron frizzen and the resulting sparks landing on a small amount of gunpower held in a pan or tray that then fired the main powder charge in the barrel. These elements can be seen in the photograph of a reproduced 17th-century gun called a snaphance or doglock. In this image, the gunflint rests against the frizzen. The flint is held in the hammer using a piece of leather to better gripe the flint when the hammer jaws are screwed down.

Although the Jamestown colonists used matchlocks and a more complicated weapon called a wheellock, the superiority of the flintlock musket was rapidly acknowledged, especially by settlers bound for America. Flintlocks were replacing matchlocks in Virginia in the 1620s and the first colonists coming to Maryland’s were armed primarily with the advanced flint muskets. While there were some matchlocks in the early years, by 1640 the Maryland militia requirement was for soldiers to carry a snaphance or flint-fired musket. The primacy of the flintlock would endure in America for almost 200 years until it was gradually replaced by the more reliable percussion cap ignition beginning in the late 1830s.

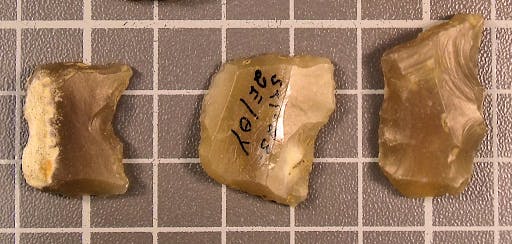

The weapon required gunpowder, lead shot and flint to operate. Both the powder and lead were brought from England but acquiring gunflints was more challenging. No British industry to make gunflints developed in England until late in the 17th century. We discovered during the 1970s excavations at the St. John’s site that professionally made gunflints were rare. There were some manufactured flints perhaps probably from the Netherlands that were of the spall type. This means that the flint is struck off a specially prepared stone core that gave it a regular shape. The spall flint was thickest where the hammer struck the stone and tapered to a thinner edge. The maker, called a knapper, then used special tools to finish and trim the flint by removing small flakes, which left small scars along the thicker edges. Below are professionally made spall flints found at St. John’s, showing with some of the finishing scars indicated by arrows.

Professionally Made Spall Gunflints found at St. John’s

Professionally Made Spall Gunflints found at St. John’s

An even rarer type of professionally made flint is of French origin and made by striking long thin blades off a stone core. The blades were then broken into squarish shaped pieces and trimmed into the correct form. There were only a few found at St. John’s and they are probably from the later part of the occupation. They are seen here. French flints are made differently from the spall type but are also manufactured from a type of flint having a consistent rich honey-brown color, which makes them distinctive. The specimen seen here on the right side is a superb example of this French flint.

French Blade Flints from the St. John’s Site

French Blade Flints from the St. John’s Site

The St. John’s evidence showed that such high-quality flints were in very short supply and colonists had to resort to other means of obtaining this essential item for hunting and defense. Archaeological analysis revealed that their solution was to turn to cobbles of English flint that probably arrived in Maryland as ship’s ballast. Flint in Britain derives mostly from ancient chalk beds that underlie much of Southern England. This is most obvious along the White Cliffs of Dover, where the hundreds of feet thick chalk layer is exposed.

The White Cliffs of Dover showing the massive chalk bed

The White Cliffs of Dover showing the massive chalk bed

Within this chalk are flint concretions. On the 2018 England trip, I observed a fresh cut into the chalk that revealed how abundant the flint cobbles really are. In the chalk, the cobbles have a white surface but are black to dark brown within. Those seen here were broken by the backhoe, thereby exposing the dark interior flint. Flints from this immense chalk layer is so common that entire buildings are constructed out of them in Southern England. Their ready availability also made them an excellent source of ballast for ships departing for America from that part of Britain.

Flint nodules exposed in the chalk at the White Cliffs of Dover.

Flint nodules exposed in the chalk at the White Cliffs of Dover.

Hundreds of fragments of English flint were found at St. John’s, both flakes and chunks of varied sizes and shapes, as seen here. The specimens showed little regularity in form or thickness.

Some of the flint flakes and pieces recovered from St. John’s

Some of the flint flakes and pieces recovered from St. John’s

But there were some that showed breakage along one or two edges that is very similar to what is observed on discarded professionally made flints. Study of the entire collection in the laboratory identified 96 specimens that seem to have been slightly modified and with edge breakage. Dr. Robert Keeler and I finally figured out that they were home-made gunflints, the first to be identified in Maryland; a few of these can be seen below.

Homemade Gunflints Discovered at the St. John’s Site

Homemade Gunflints Discovered at the St. John’s Site

Their shapes range from square to rectangular to trapezoidal, and the thickness varies considerably. Flake scars occur in all directions with little evidence of the careful workmanship seen on the European specimens. The only traces of modification are small scars along some of the edges where the maker(s) used a crude chipping technique to produce a somewhat more regular shape.

What was especially intriguing is where these flint debris are found. Mapping of the flint by Robert Keeler for his doctoral dissertation on the St. John’s site revealed that the flints fragments clustered around the back doors of the house and kitchen at the site. This implies that a colonist, needing flints for his weapon, acquired a cobble, sat near or in the doorway and using another stone or metal object, banged away at the cobble to knock off pieces of flint. That activity is replicated below by Charles Fithian, posing as a colonist in need of gunflints.

Trying to make some gunflints, c. 1650

Trying to make some gunflints, c. 1650

Study of these artifacts indicates that the colonists had no real idea of how to reduce a cobble in the way professional European knappers or Native Americans would have done, but they could knock off flakes, no doubt cutting their fingers occasionally in the process. I say this because my own efforts at flint knapping have never ended without a bit of bloodshed. Nevertheless, numbers of flint flakes could be made by this crude but effective procedure and a colonist could then sort through them, looking for a few pieces appropriately shaped and thick enough to serve as gunflints, as seen here.

Selecting flakes that might serve as gunflints

Selecting flakes that might serve as gunflints

Those pieces of flint were then modified slightly by removing small flakes from the edges to produce a more usable shape. The new gunflint would then be fixed onto the weapon and could fire it for a period of days or weeks, or even longer. Eventually, a flint becomes battered and reduced in size or even misshapen from breakage and it will no longer reliably produce the necessary sparks. It is then discarded and replaced. Examination of these St. John’s specimens indicates that they were used, displaying the battering and breakage that is typically found on gunflints.

Initially, we thought that this might have been unique to St. John’s. However, subsequent excavations on the Leonard Calvert house site has shown that people there, especially the soldiers garrisoned in Pope’s Fort which surrounded the house in the 1640s, did exactly the same thing. English flint was also used to make strike-a-lites and a few specimens show use as a scraper, but the vast majority of the pieces displaying evidence of use are gunflints. This same activity has since then been identified on other Maryland and Virginia sites. It appears that by the last decades of the 1600s, professionally made flints became more available and gunowners no longer needed to make their own flints. But for the first 40 years or so of Maryland, colonists were forced by necessity to make do in many ways, having limited resources and being cut off from resupply for many months each year. Homemade gunflints are a classic example of some of these activities required for survival, and the first direct physically evidence for it in the Chesapeake Bay region came from the archaeological excavations at St. Mary’s City.

About the Author

Dr. Miller is a Historical Archaeologist who received a B. A. degree in Anthropology from the University of Arkansas. He subsequently received an M.A. and Ph.D. in Anthropology from Michigan State University with a specialization in historic sites archaeology. Dr. Miller began his time with HSMC in 1972 when he was hired as an archaeological excavator. Miller has spent much of his career exploring 17th-century sites and the conversion of those into public exhibits, both in galleries and as full reconstructions. In January 2020, Dr. Miller was awarded the J.C. Harrington Medal in Historical Archaeology in recognition of a lifetime of contributions to the field.